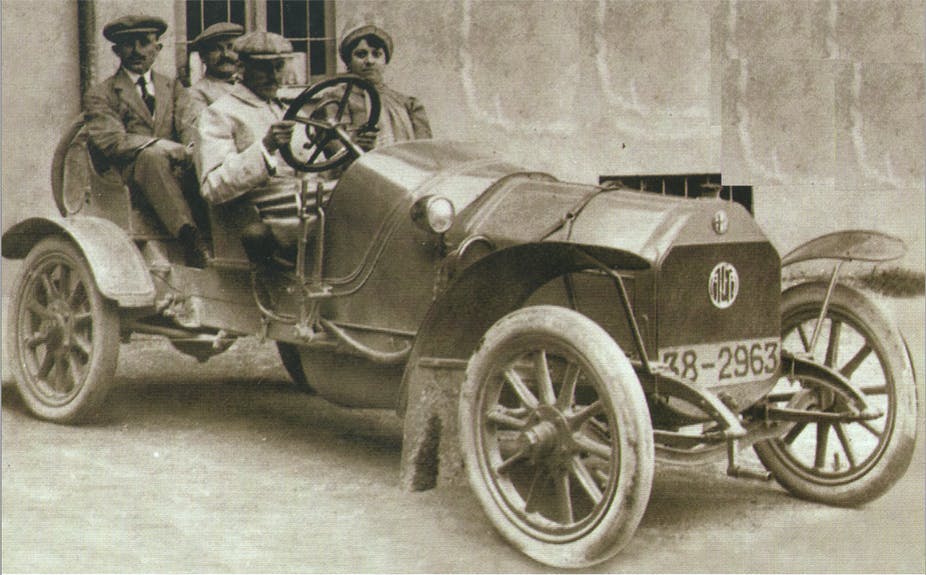

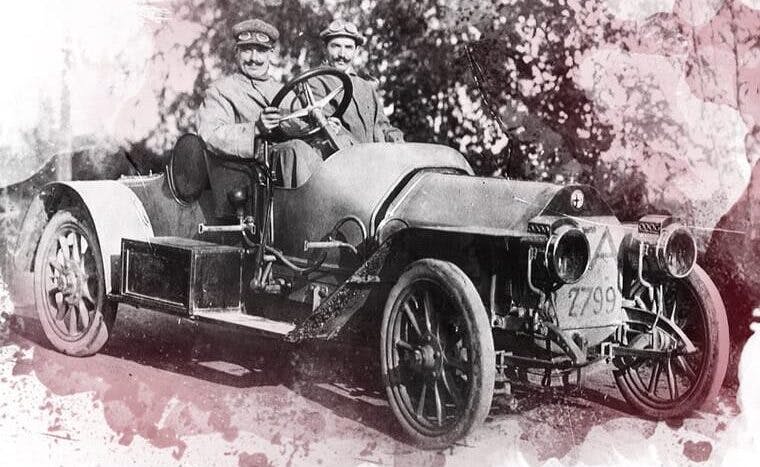

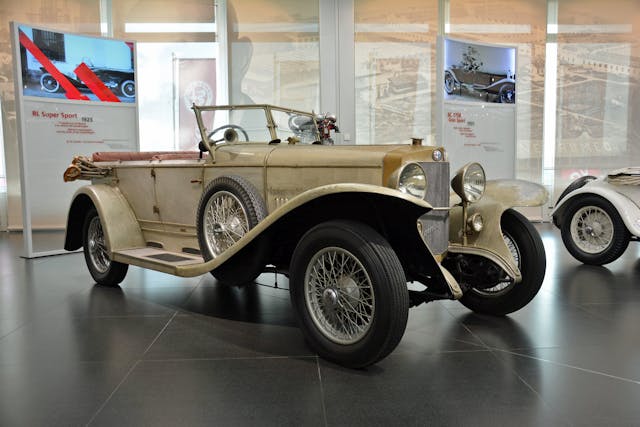

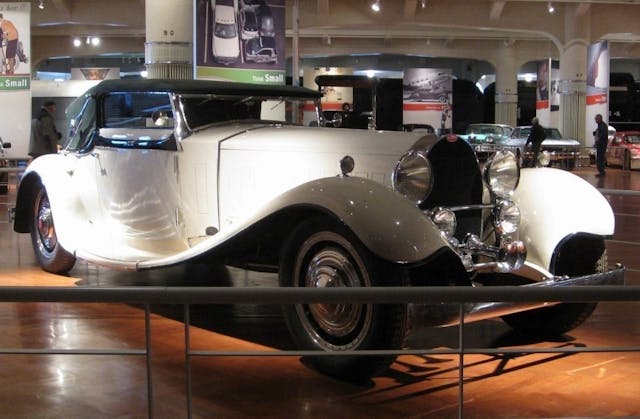

Italians are renowned for their obsessive attention to the aesthetics of pretty much everything. As a result, the country enjoys a reputation for style and flair that the marketing teams of brands like Alfa Romeo or Maserati waste no opportunity to exploit to their advantage.

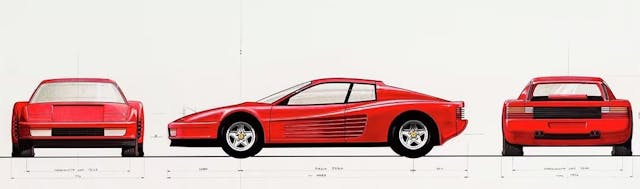

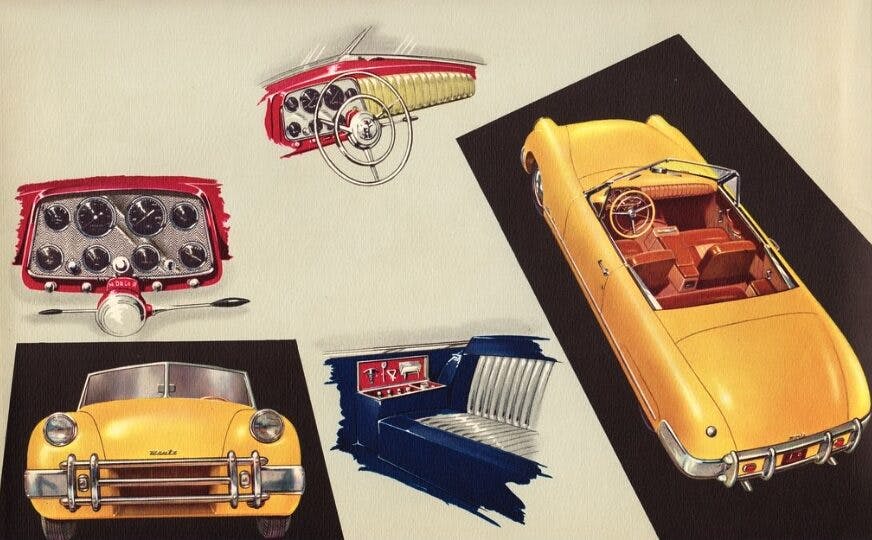

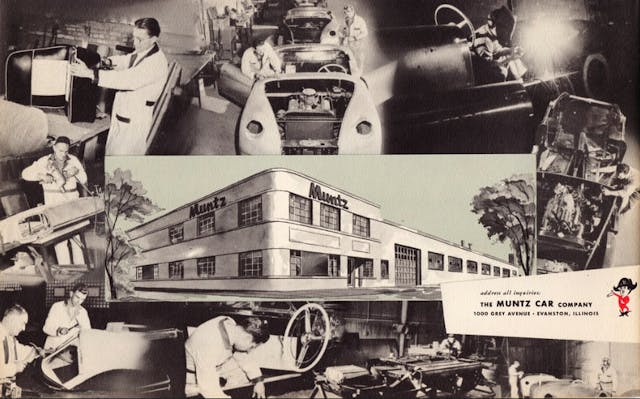

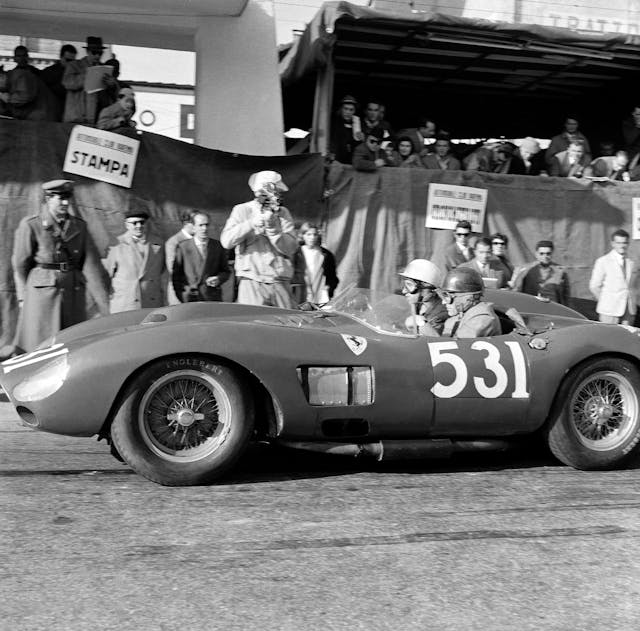

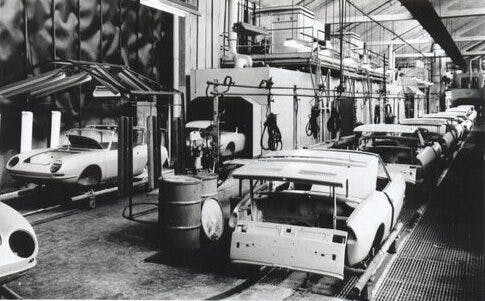

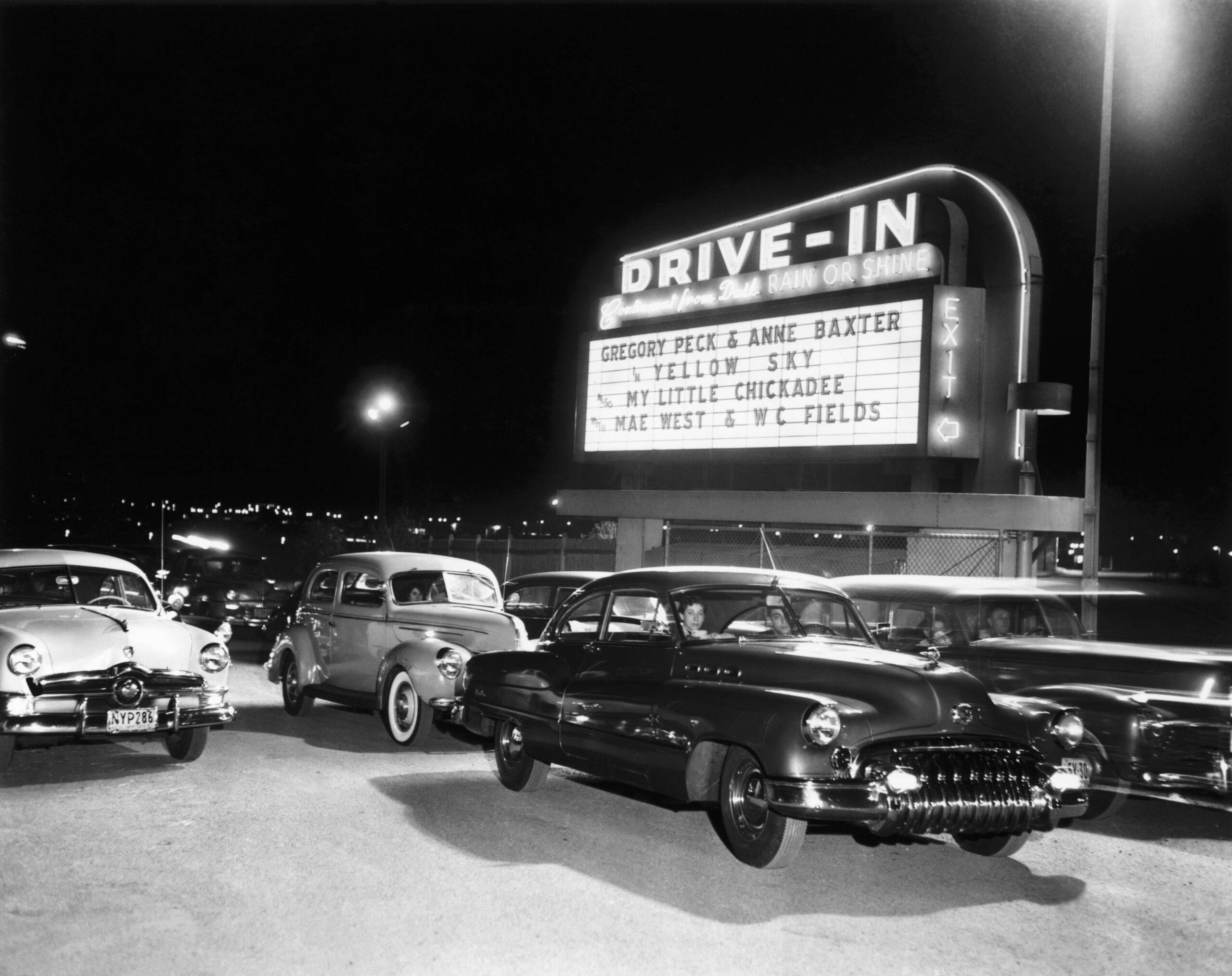

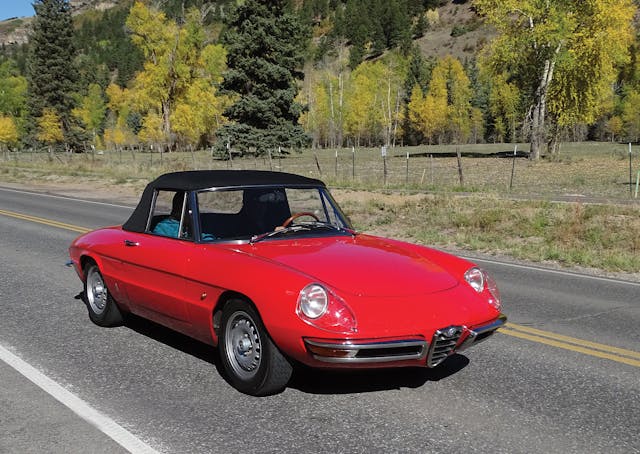

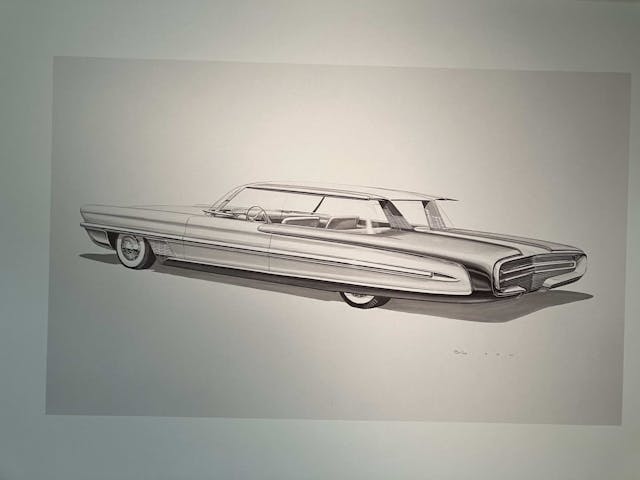

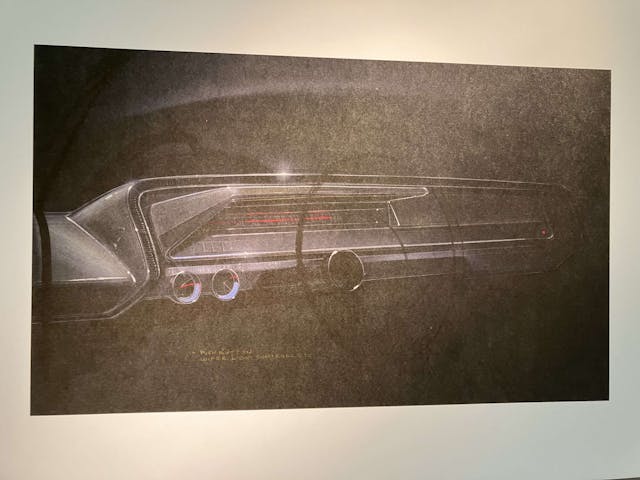

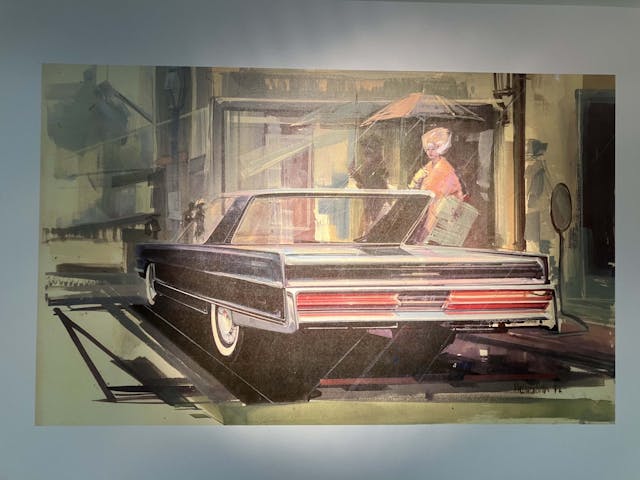

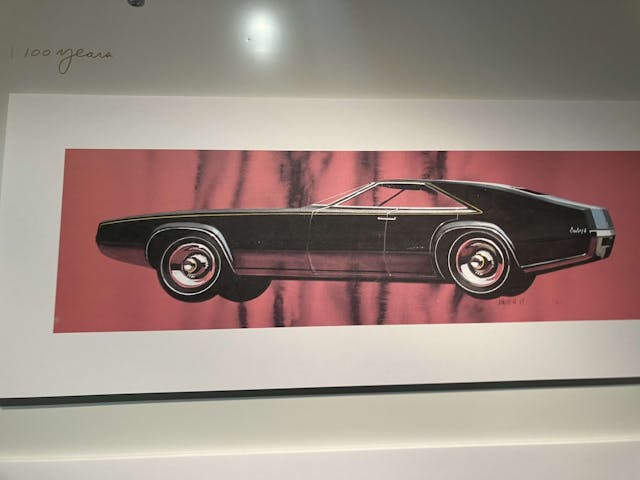

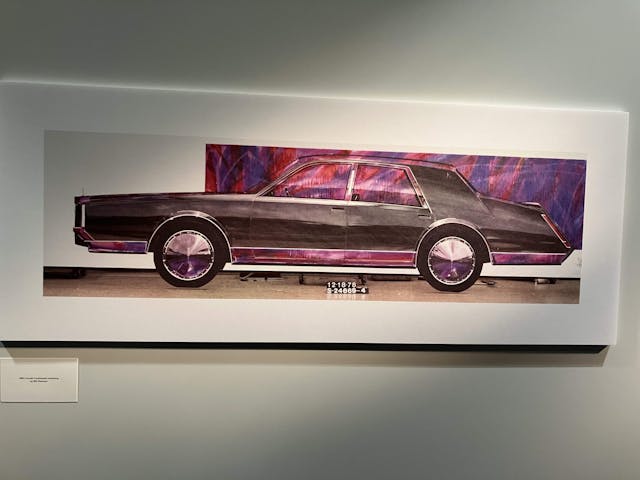

Yet, few would argue that, when it comes to car design, that reputation was mainly established between the 1950s and the 1980s, the golden era of the Italian “Carrozzieri.” These were a handful of small firms located around Turin that, at the height of their creative powers, managed to exert an outsize influence on the aesthetic development of the automobile worldwide.

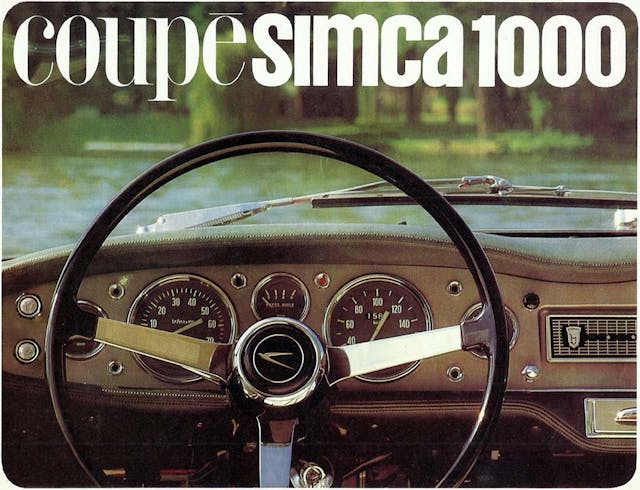

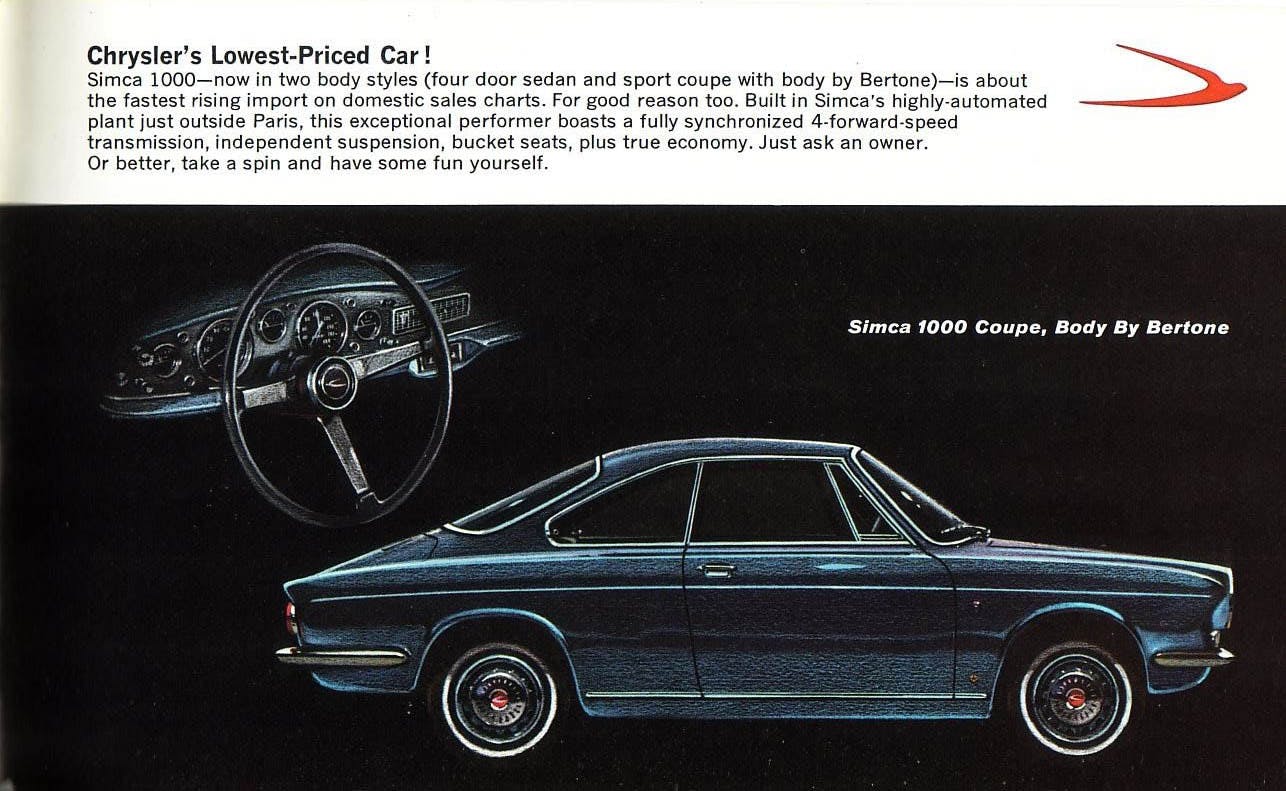

But it’s plain to see that those days are gone. Bertone is no more, ItalDesign is an outpost of VW, and if you want your new car to come with a Pininfarina badge, your only choice is the Battista hypercar.

So, what went wrong?

The question may be simple, yet the answer is anything but. The downfall of Italy’s famed design houses wasn’t triggered by a single event or circumstance. Instead, it was a gradual process characterized by multiple contributing factors. But to understand what knocked the likes of Pininfarina and Bertone off their perches, we first need to look at how they got there in the first place.

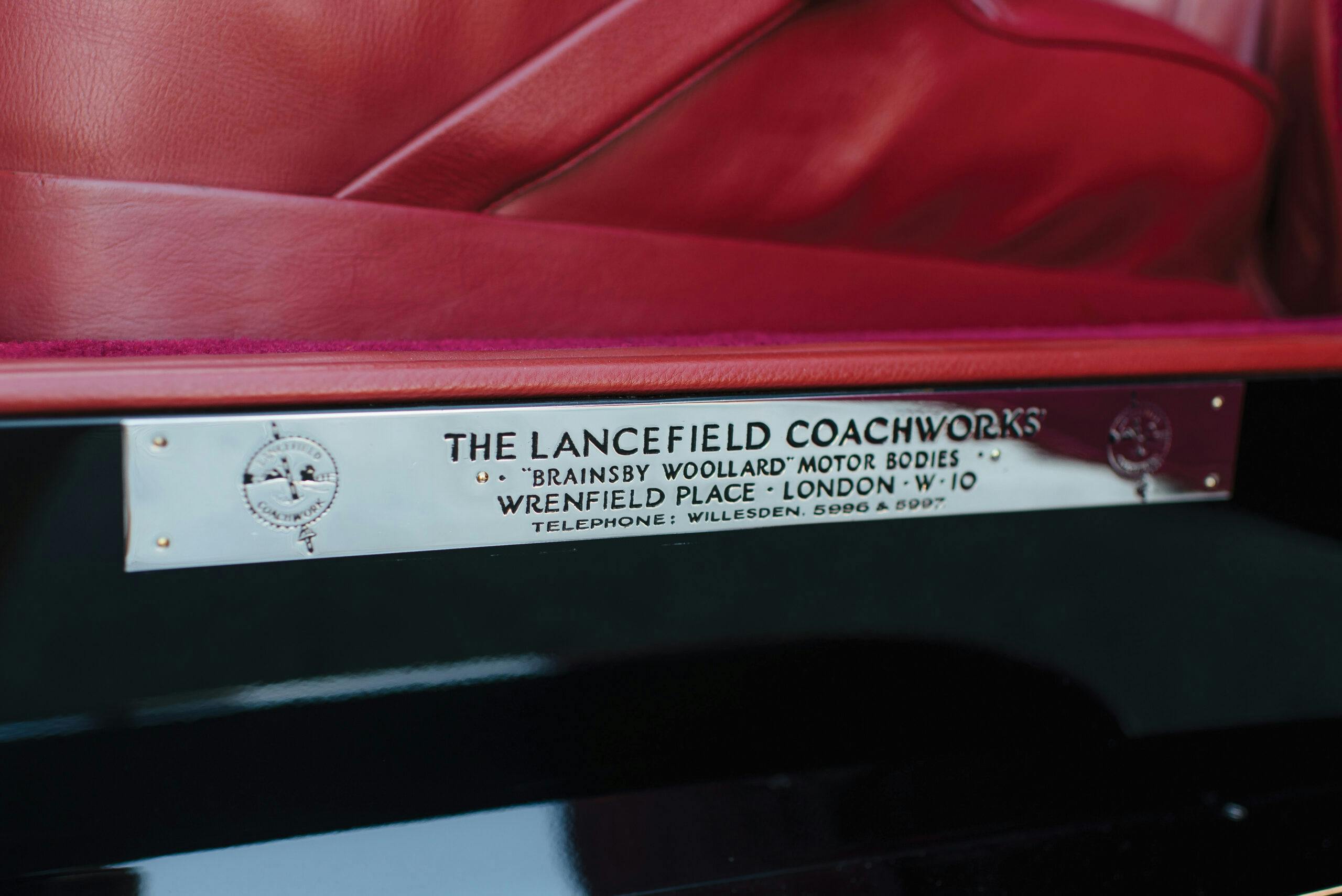

The postwar years weren’t kind to the European coachbuilding industry. The sector’s traditional client pool was dwindling, and as the continent’s automobile industry embraced unibody construction, so was the supply of suitable donor chassis to work on.

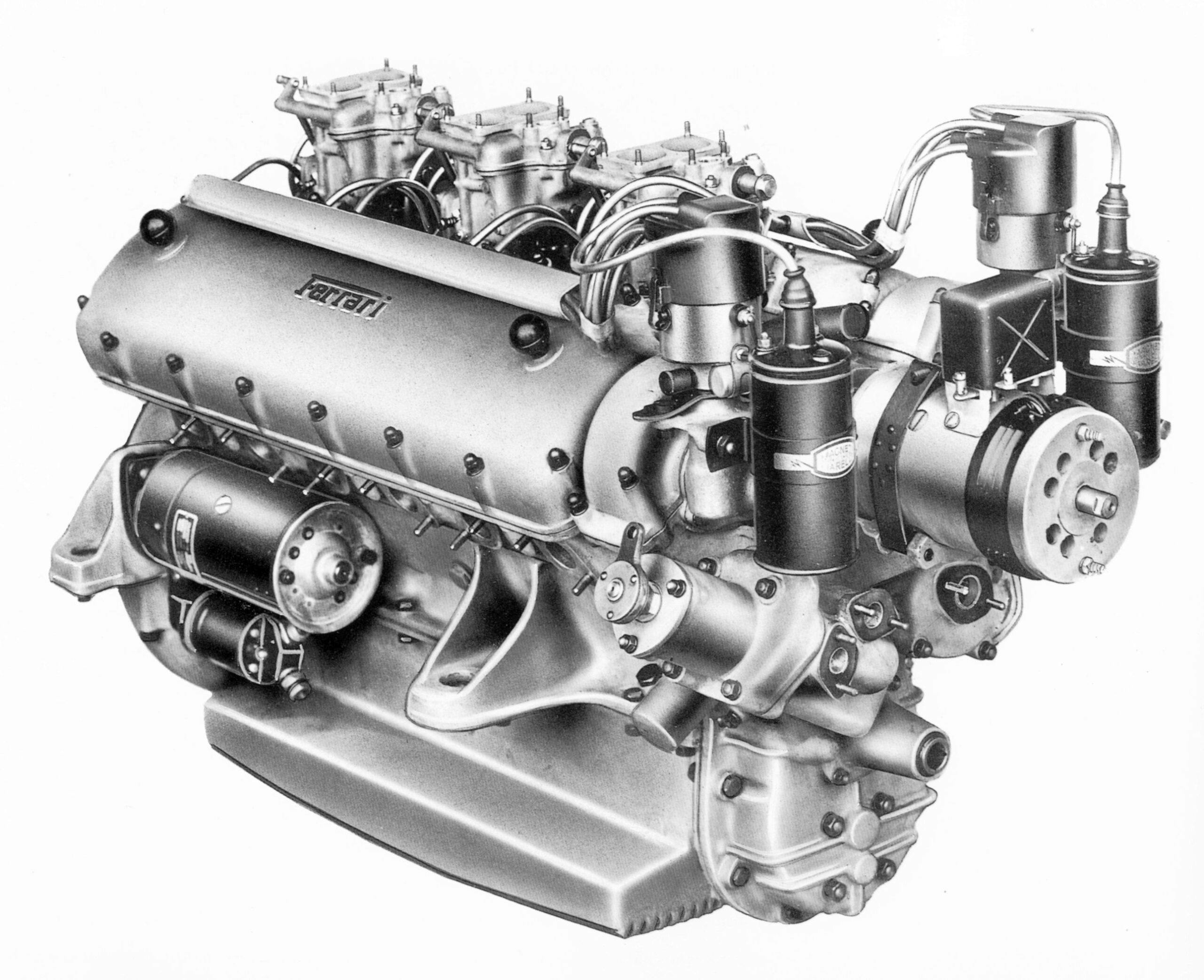

By 1955, many prestigious Italian names from the pre-war era, such as Castagna and Stabilimenti Farina, were gone. The few coachbuilding firms that survived this tumultuous period were those with closer ties to the local automakers. These were the strongest, most resourceful outfits that could work with unibody structures and take care of small production runs—all while serving as actual design partners, too. Genuine one-stop shops that, on short notice, could ease the pressure from an automaker’s factory and design office.

That’s because while the switch to chassis-less construction made for lighter, more efficient cars, it also made tooling up for low-volume derivatives like coupès or convertibles significantly more expensive. And that’s where companies like Pininfarina and Bertone entered the picture. Outsourcing their design and production allowed Fiat, Lancia, and Alfa Romeo to offer sporting derivatives of their regular models without investing in additional production capacity. This became even more critical by the second half of the 1950s, as a booming Italian economy sent the demand for new cars through the roof.

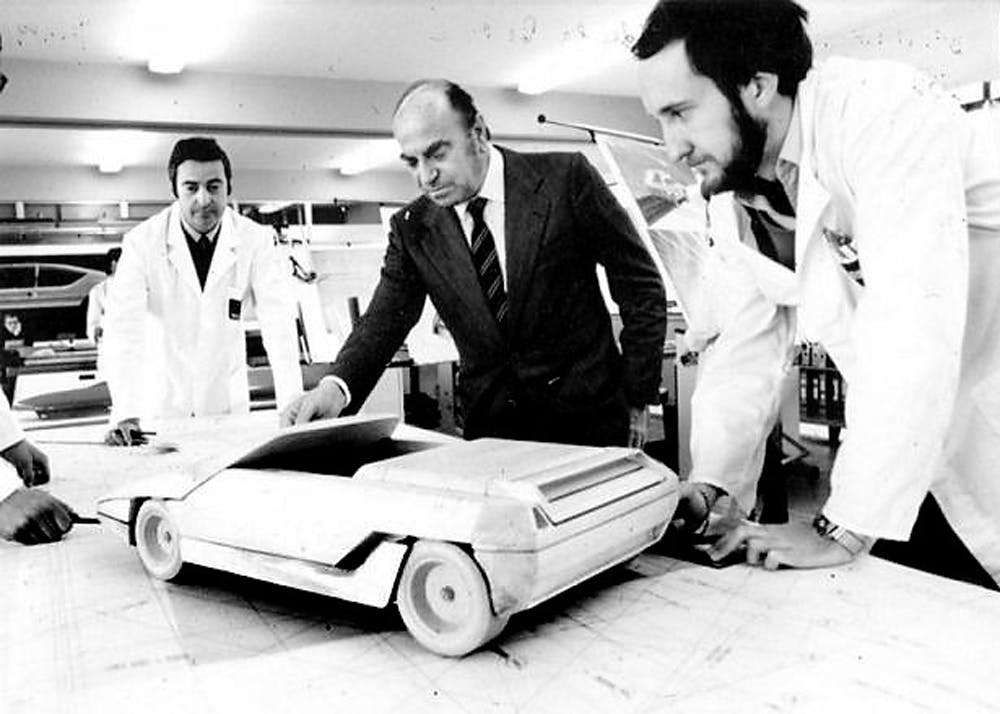

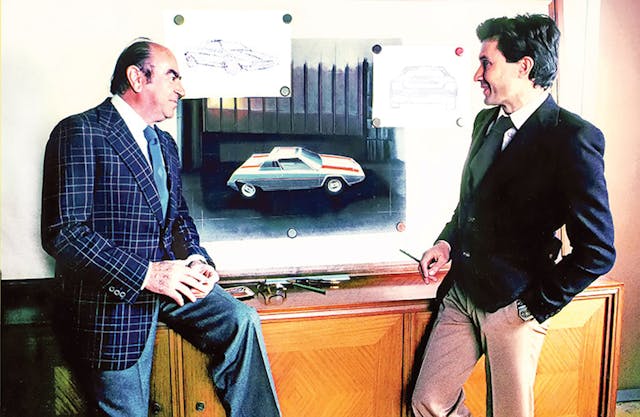

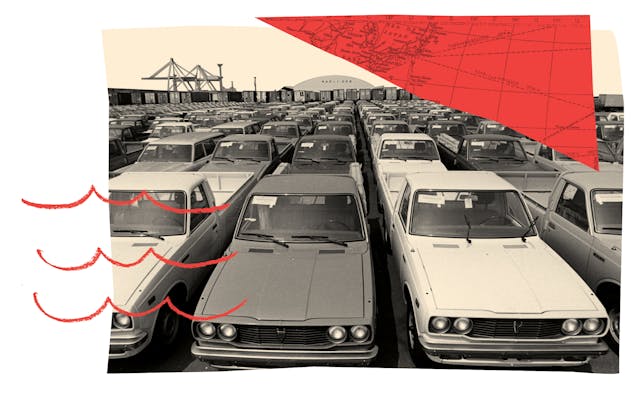

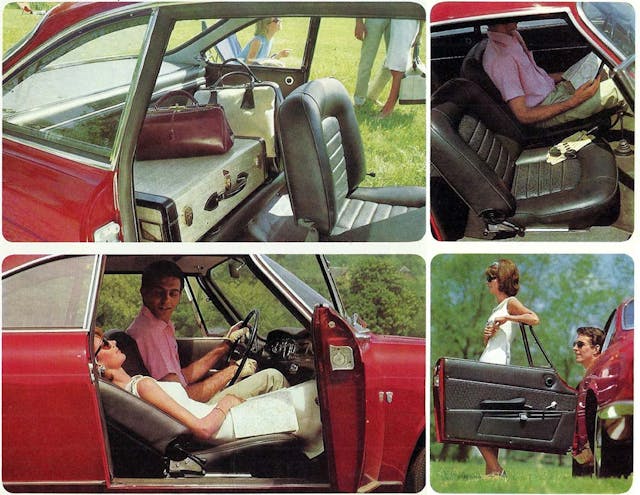

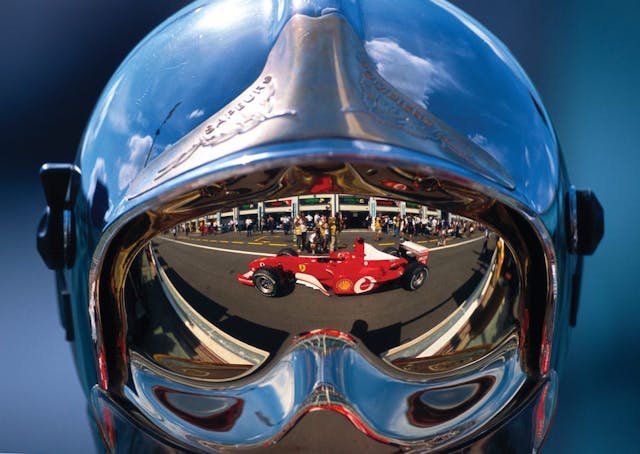

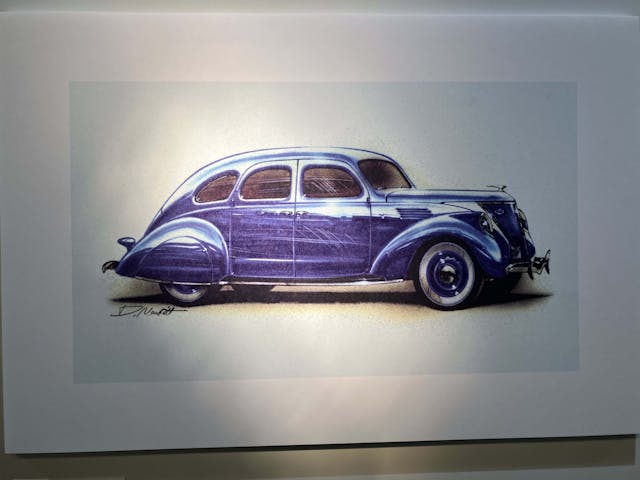

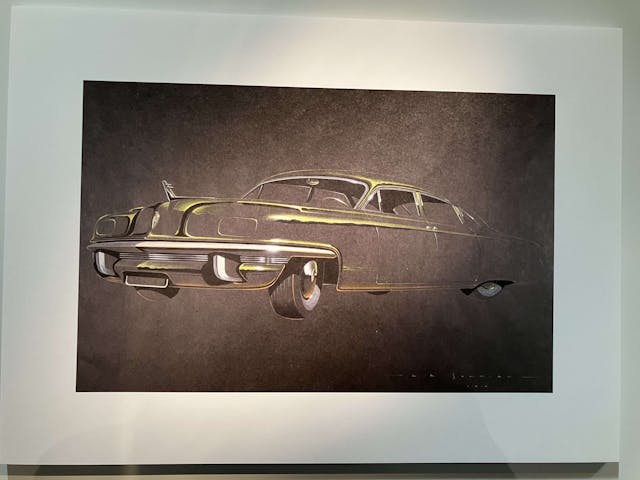

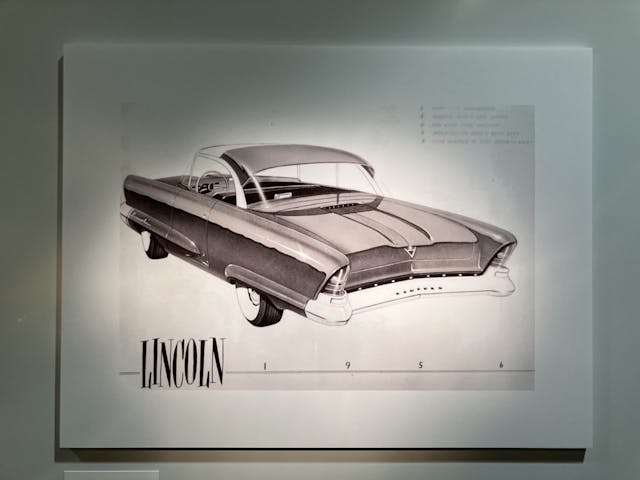

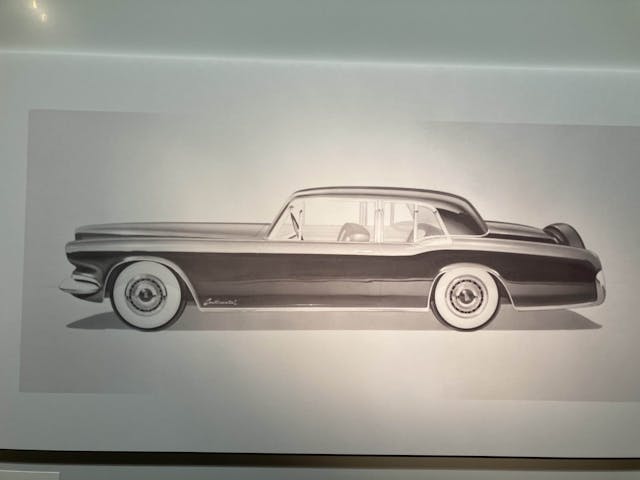

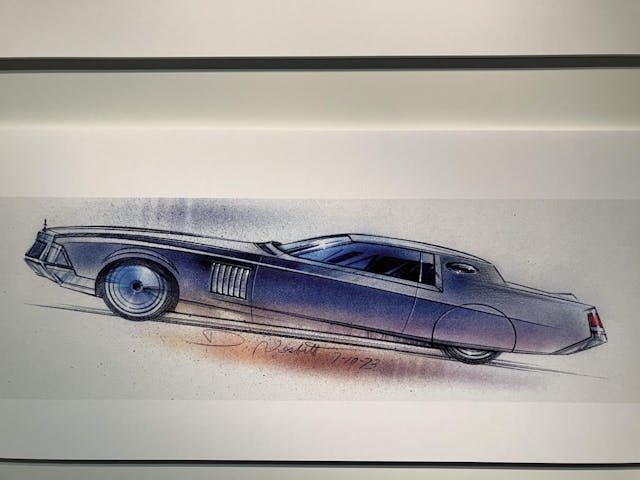

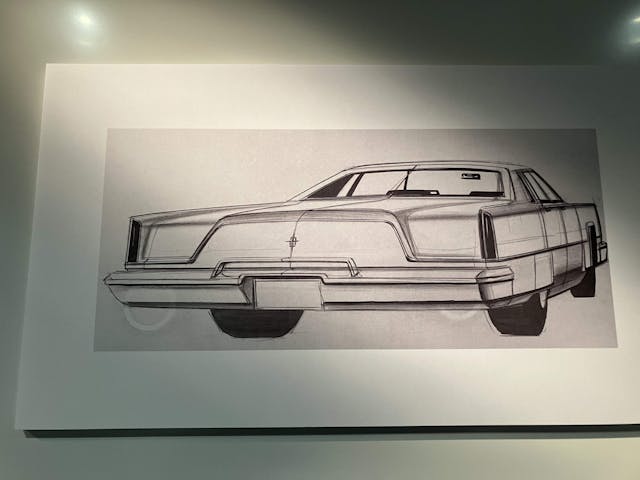

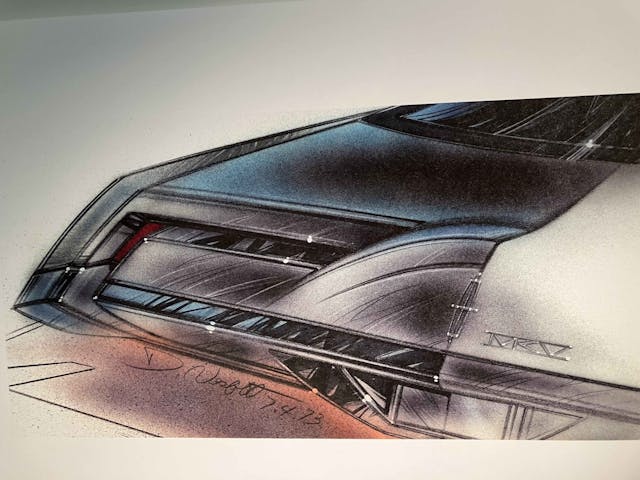

By the mid-’60s, these lucrative contract manufacturing arrangements had transformed Pininfarina and Bertone into small industrial empires. Both companies built car bodies by the thousands, yet their fortunes depended as much on ideas as they did on sheet metal. Being perceived as the cutting edge of automobile design was crucial to keep commissions coming in, so wowing the crowds at the Turin, Paris, or Geneva motor shows with sensational show cars was an integral part of these firms’ business. And the results were as spectacular as the cars themselves: Design commissions came pouring in from France to Japan and everywhere in between. It seemed the Turinese masters could do no wrong, but their success was due in no small part to favorable circumstances.

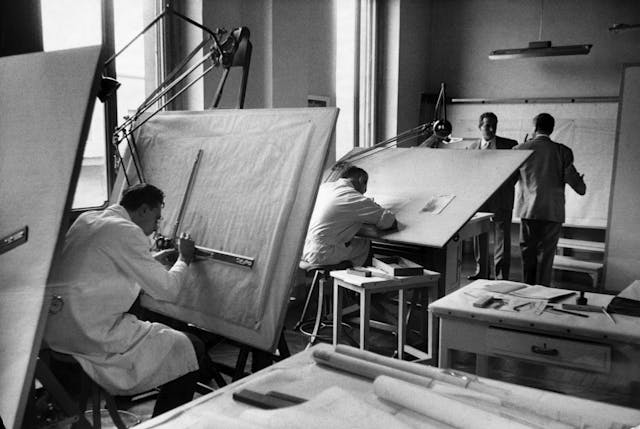

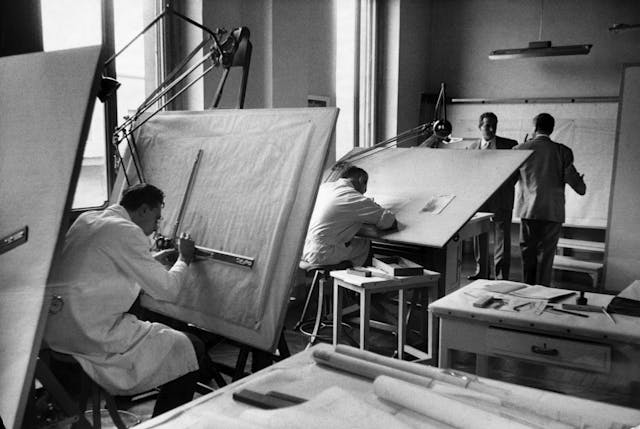

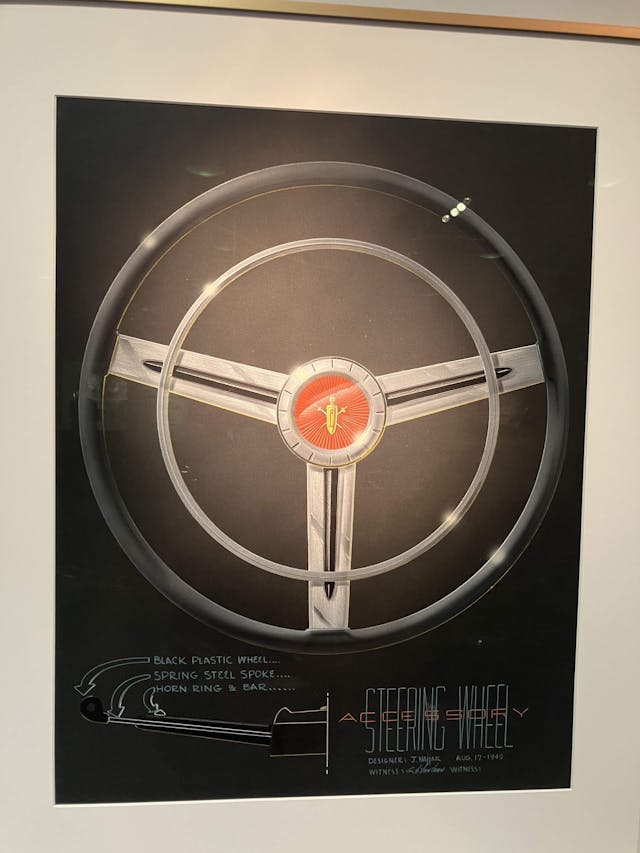

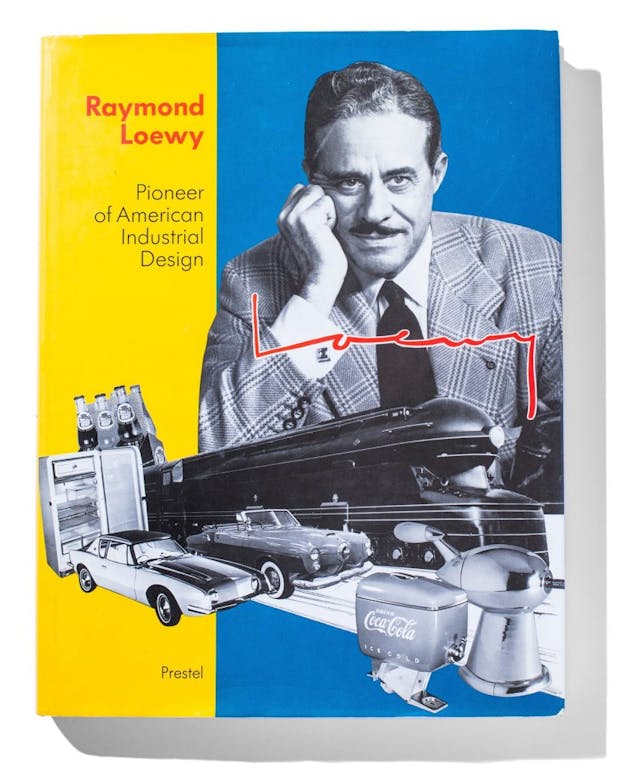

As we intend it today, car design was practically invented in Detroit in the late 1920s when GM established its “Art & Colour” section. It didn’t take long for each of the Big Three to have a well-funded and fully-staffed design department. But, strange as it may sound to our modern ears, during the ’50s and ’60s, most European automakers had yet to realize the essential role design played in market success. If they had an in-house design team, it was often understaffed and placed under the engineering department’s thumb. Management frequently had little understanding or appreciation for design matters and, lured by their flashy dream cars, didn’t think twice about handing the job to the Italians.

Of course, that’s not to say these people weren’t good. Unencumbered by the internal pressures the home teams were subjected to, the Italian studios repeatedly delivered the freshest, most original proposals. Sometimes, when one particular automaker was stuck in a dangerous creative rut, that outside input—think Giugiaro’s work for VW in the 1970s, for example—could even prove vital. But nothing lasts forever, and as the 1980s gave way to the 1990s, dark storm clouds were already looming on the horizon.

The first cracks began appearing right in the contract manufacturing business that had served Bertone and Pininfarina so well. Quality standards across the industry increased, while more advanced, flexible production methods allowed different cars to be made on the same line. As a result, automakers lost the incentive to outsource the production of lower-volume models. Moreover, if an international customer faltered, falling back on Fiat’s shoulders was no longer possible. Italy’s former industrial giant was all but broke heading into the turn of the new millennium and could no longer offer the support that had been so crucial four decades earlier. Few things can dig a larger hole in a company’s finances quicker than an idle factory, but the problems didn’t stop there.

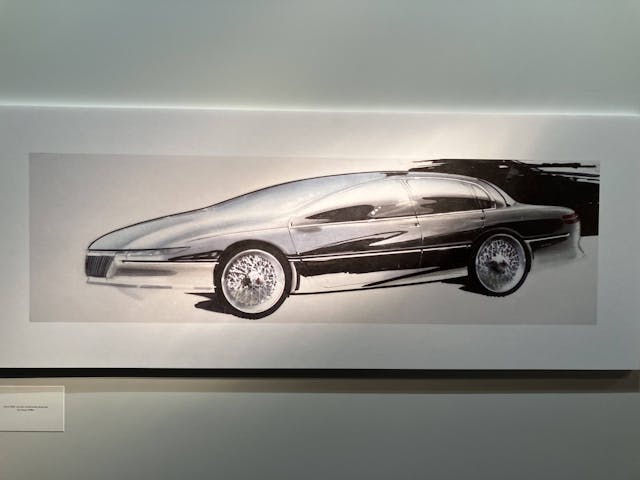

By the time the last 747 full of Cadillac Allantés left Turin’s airport, design culture was much more widespread worldwide. Automotive executives were now acutely aware of design’s importance, and wanted to keep tighter control over it. Consequently, manufacturers invested heavily in their own design studios and often had multiple ones on different continents. With that, any incentive to involve third parties in the process was gone.

Especially when said third party counted most of your competitors among its customers. In an excellent biography published a few years ago, the legendary designer Ercole Spada shared a poignant anecdote from his time at BMW. He recalled how the company routinely asked each of Turin’s most prominent studios for proposals despite not intending to pursue any. But, since Pininfarina, Bertone, and ItalDesign all worked with BMW’s rivals, having these companies “compete” against its own design studio was, for the Bavarian firm, an indirect way to get a glimpse of its rivals’ general direction.

Last but certainly not least, complacency set in. There may still have been a space for Turin’s storied design firms in the modern era if they had kept their foot hard on the accelerator and their gaze locked on the horizon. Perhaps even more than in their 1960s heyday, being at the forefront of automobile design was a matter of life or death. Yet, one look at Bertone’s post-2000 output is enough to see why their phone stopped ringing.

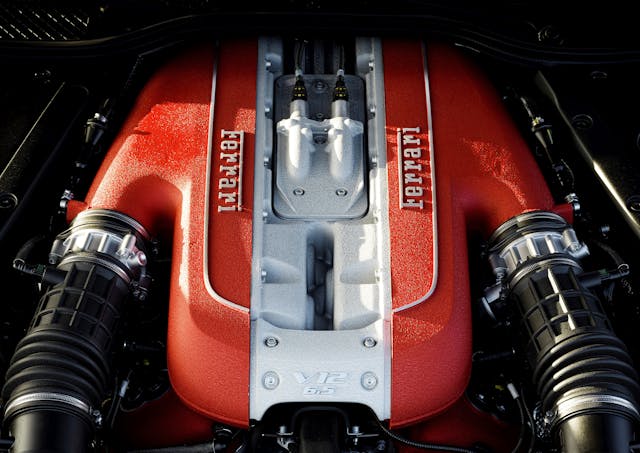

Of course, Pininfarina is still around. Its latest work, the lovely Morgan Midsummer, shows that the company hasn’t lost its touch. But the days in which every Ferrari and every Peugeot on sale was a Pininfarina design are gone, never to return.

Nevertheless, it can be argued that what was created all those years ago in Turin continues to wield a certain influence on automobile design today. As a part of our shared cultural heritage, it’s in the back of every car designer’s mind, providing inspiration and being reinterpreted in novel ways. There are many examples out there, but the best one may be Hyundai’s brilliant Ioniq 5. It’s a resolutely contemporary and highly distinctive design, yet its design language’s roots are in Giugiaro’s “folded paper” cars from the 1970s.

Ultimately, the tale of Turin’s fallen design giants is as much about their amazing cars as it is about the fleeting nature of success. Left behind by the industry they once ruled, what’s left of the Italian “Carrozzieri” currently faces an uncertain future. What is certain, however, is that their massive legacy will stay with us for a very, very long time.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

The post The Rise and Fall of Turin’s Design Firms appeared first on Hagerty Media.

]]>

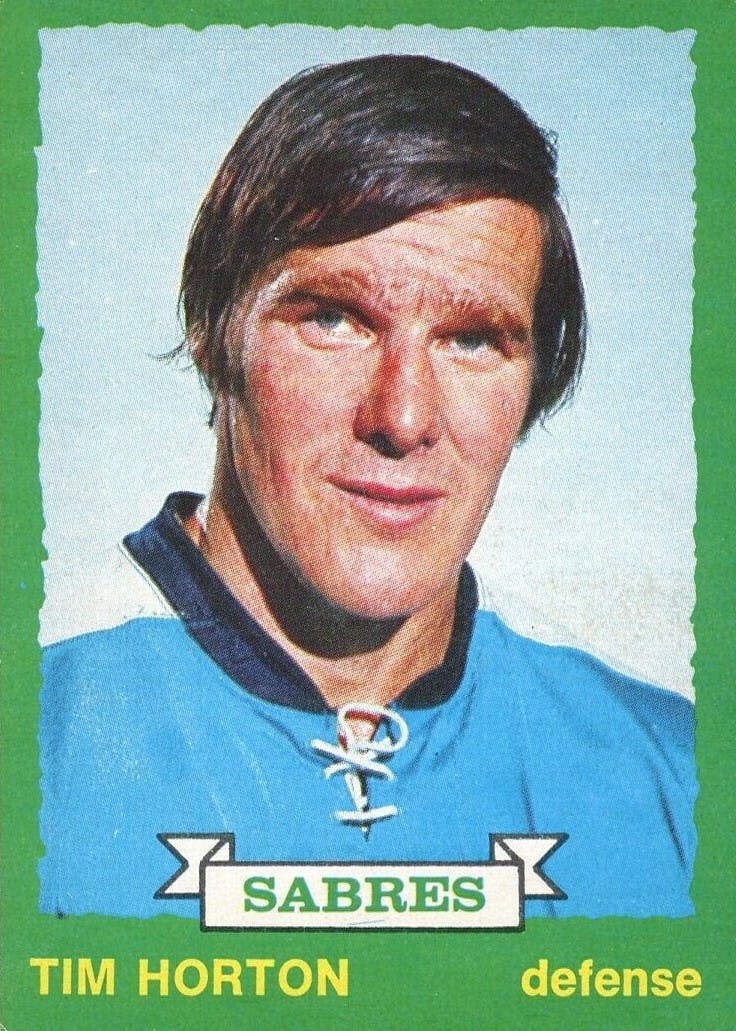

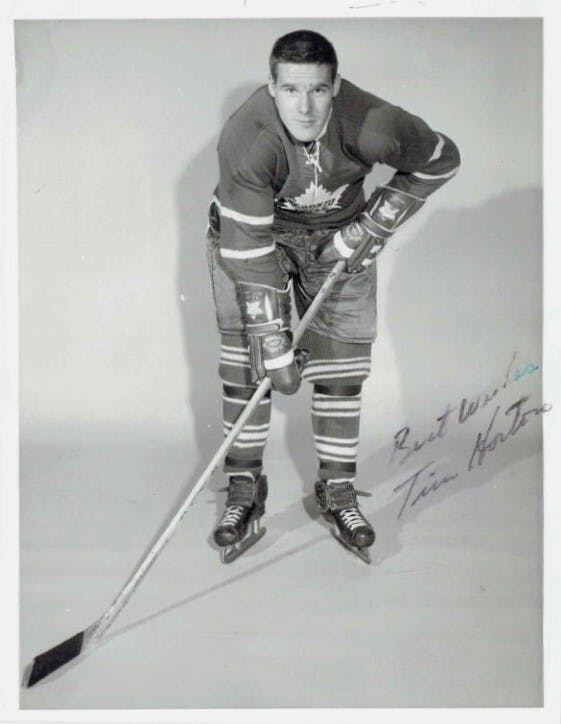

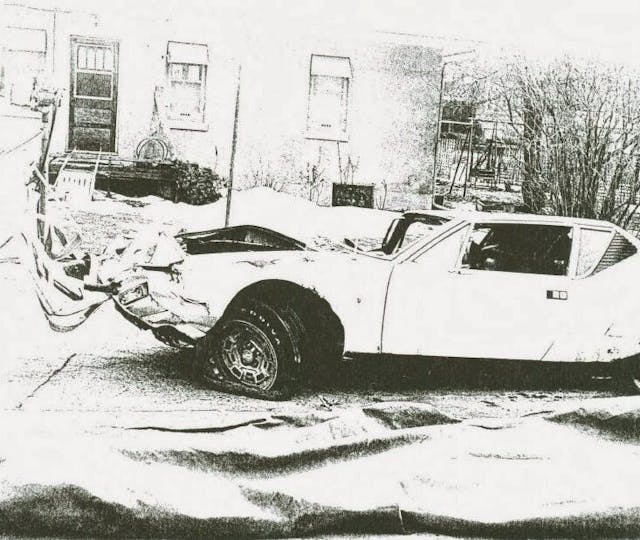

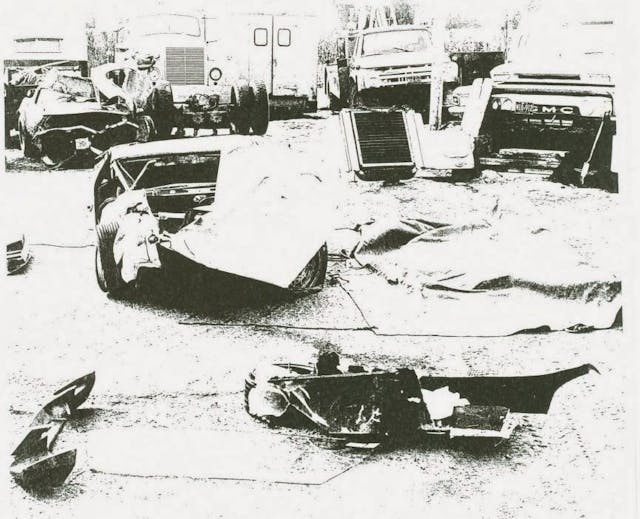

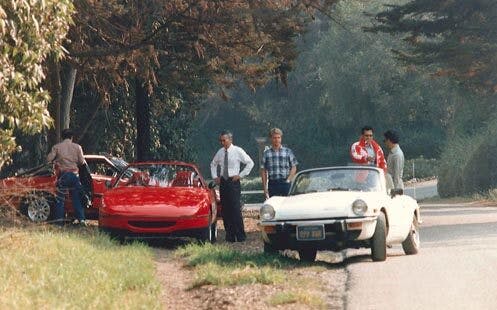

Most of the 20th-century Italian cars you’ll find in North American car graveyards today will be Fiat 124 Sport Spiders and X1/9s, with the occasional Alfa Romeo 164 thrown in for variety. For the first Italian machine in the Final Parking Space series, however, we’ve got a much rarer find: a genuine Maserati Biturbo Spyder, found in a boneyard located between Denver and Cheyenne.

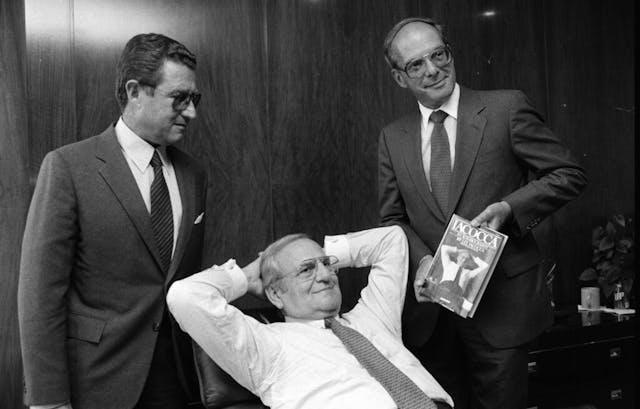

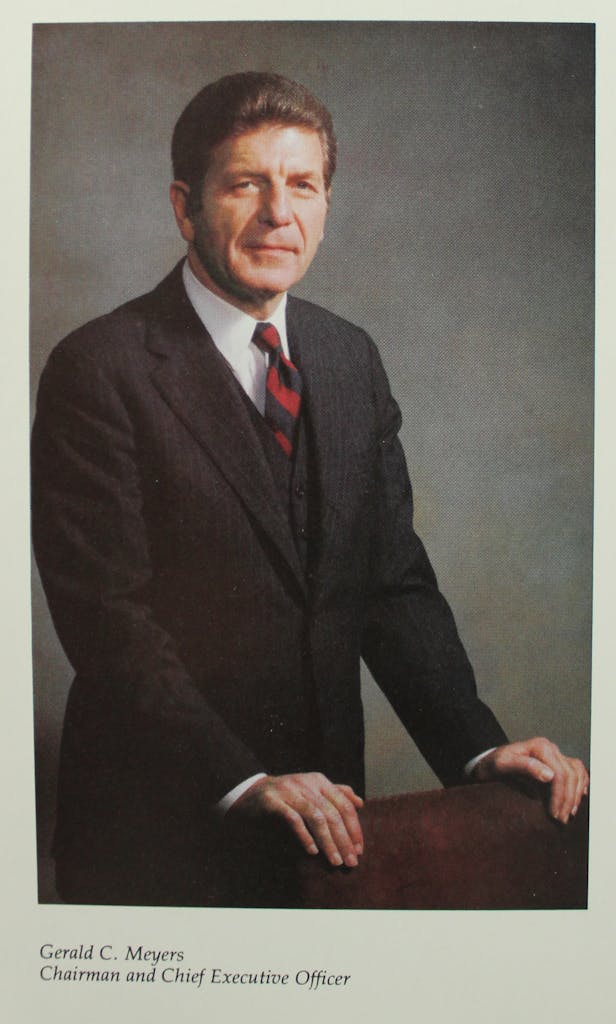

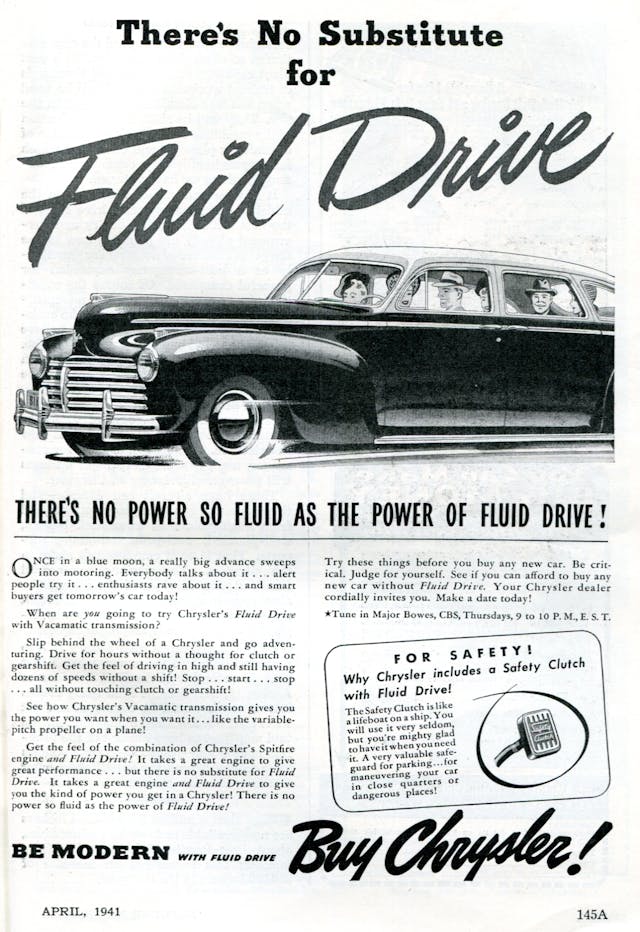

1989 was an interesting year for the Maserati brand, because that was when the longtime friendship between Maserati owner Alejandro de Tomaso and Chrysler president Lee Iacocca resulted in a collaboration between the two companies that produced a car called, awkwardly, Chrysler’s TC by Maserati.

The TC by Maserati was based on a variation of Chrysler’s company-reviving K platform and assembled in Milan. I’ve documented five discarded TCs during the past decade, and those articles have never failed to spur heated debate over the TC’s genuine Maserati-ness.

In fact, I’ve managed to find even more examples of the Biturbo than the TC during my adventures in junkyard history, and even the most devoted trident-heads must accept those cars as true Maseratis.

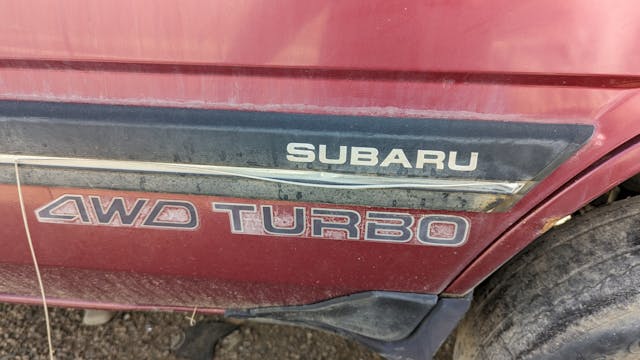

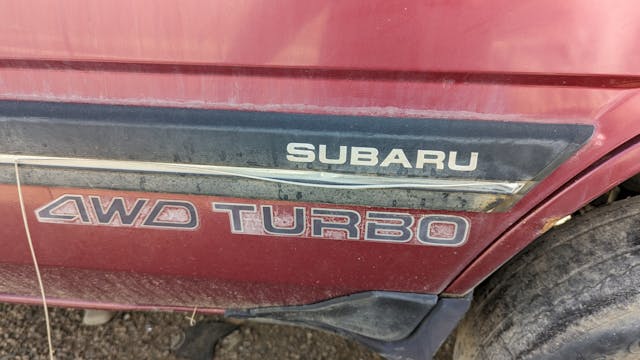

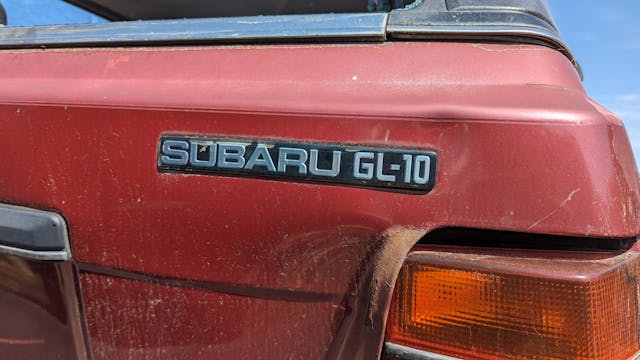

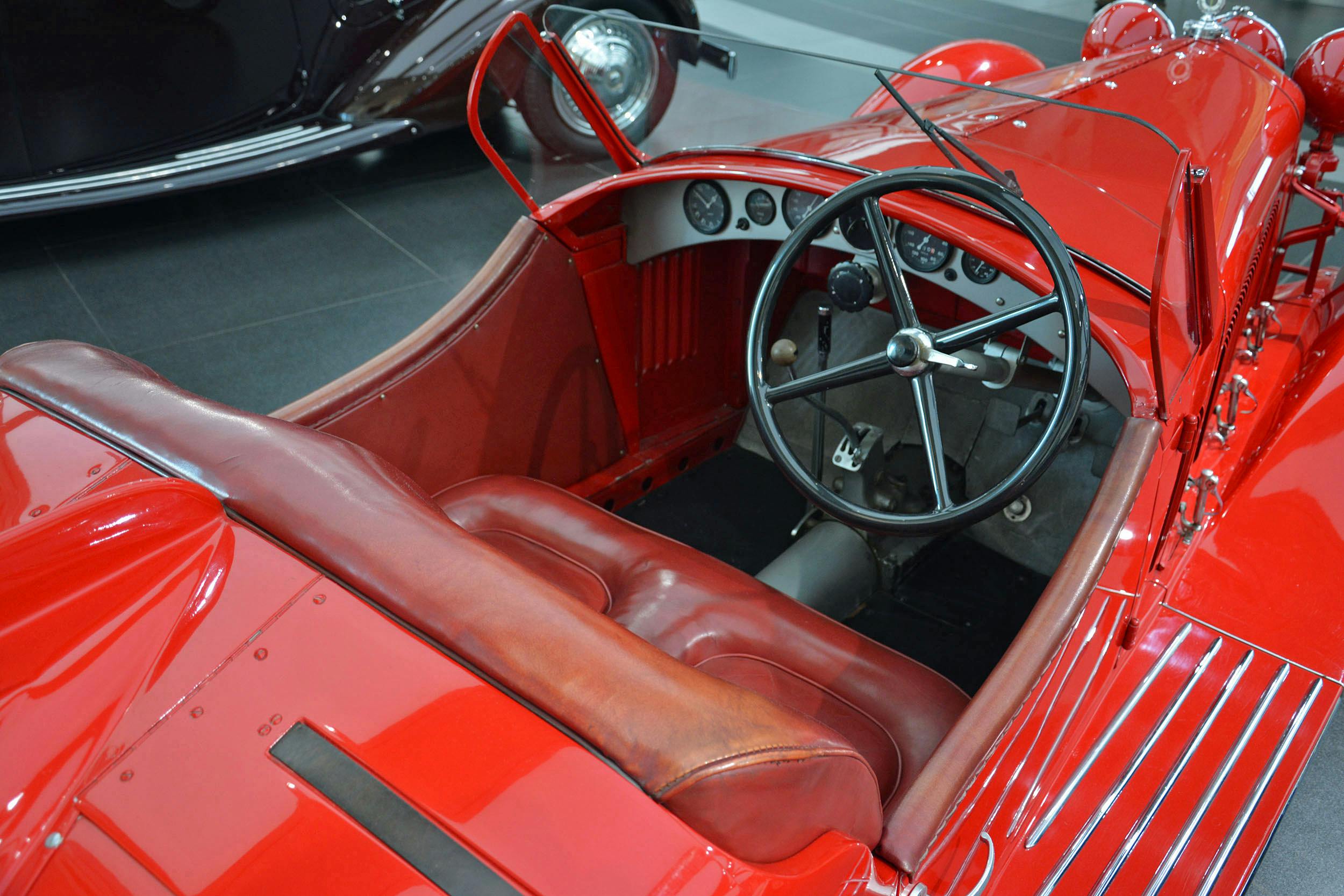

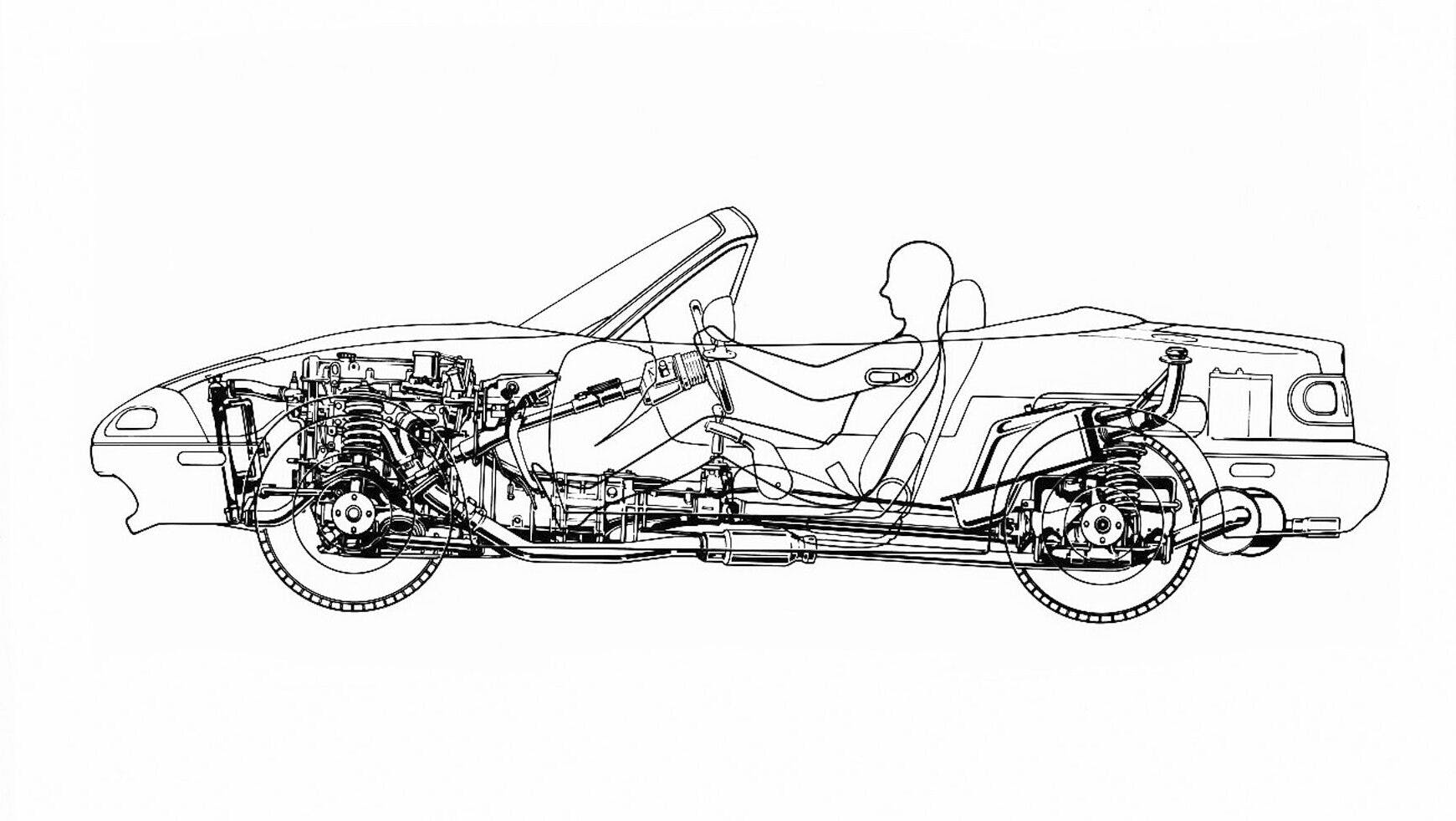

The Biturbo was Maserati’s first attempt to build a mass-production car, and it went on sale in the United States as a 1984 model. It was available here through 1990, at various times as a four-door sedan (known as the 425 or 430), a two-door coupe, and as a convertible (known as the Spyder). This car is the first Spyder I’ve found in a car graveyard.

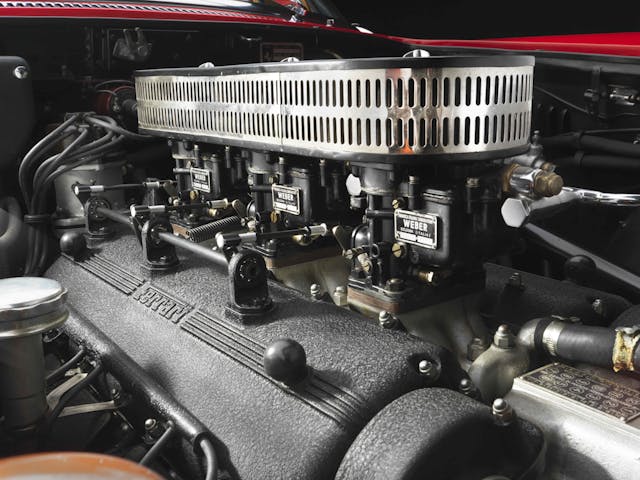

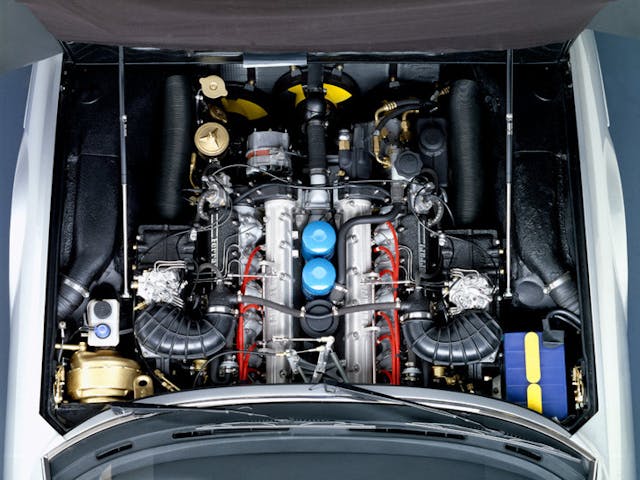

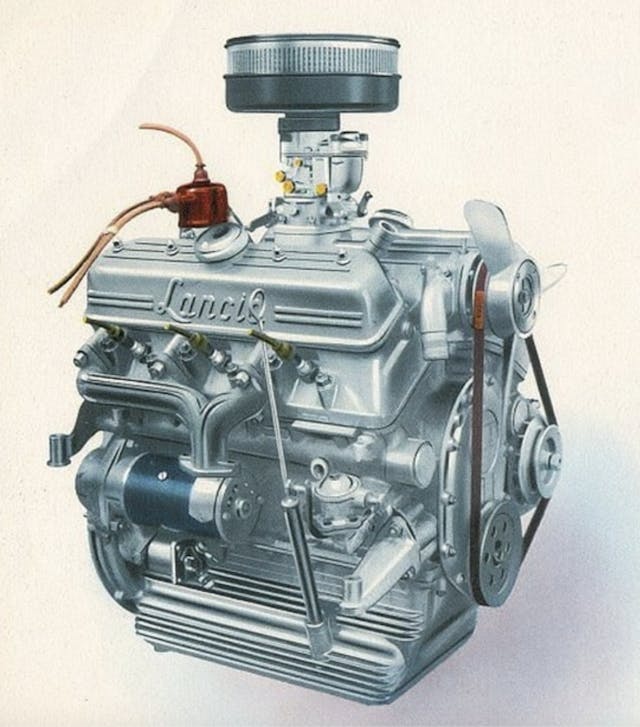

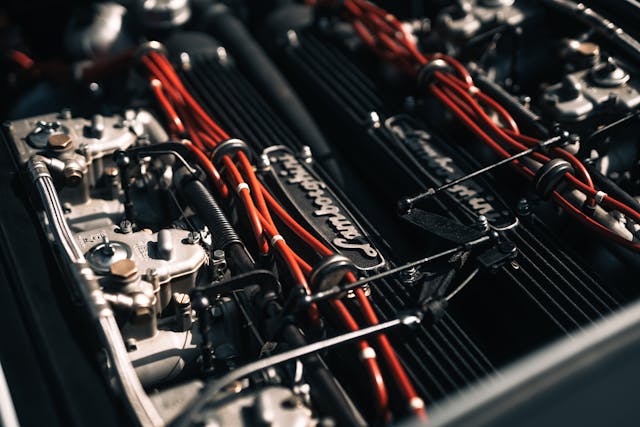

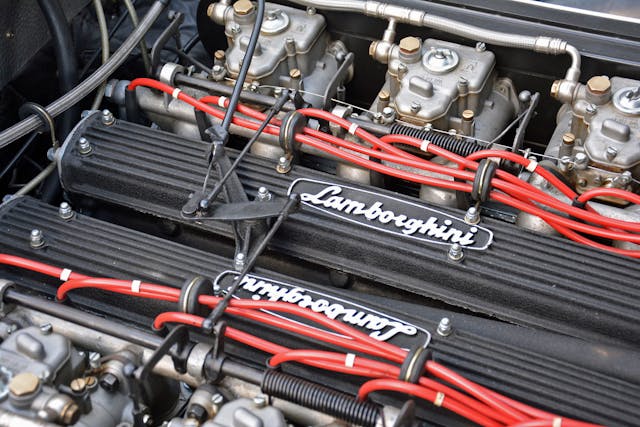

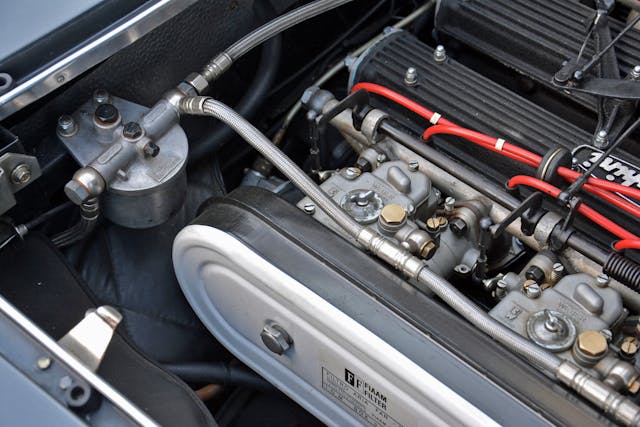

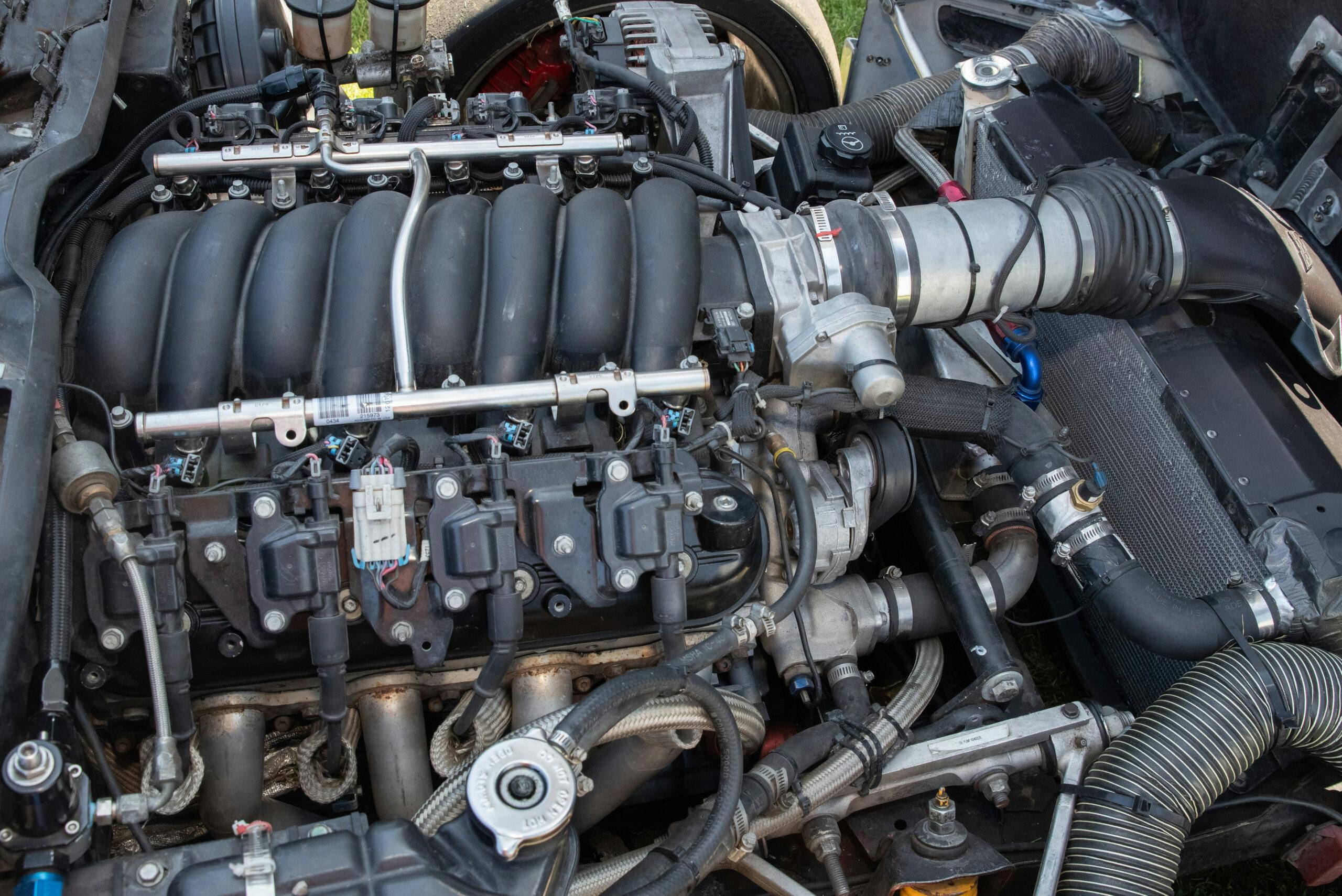

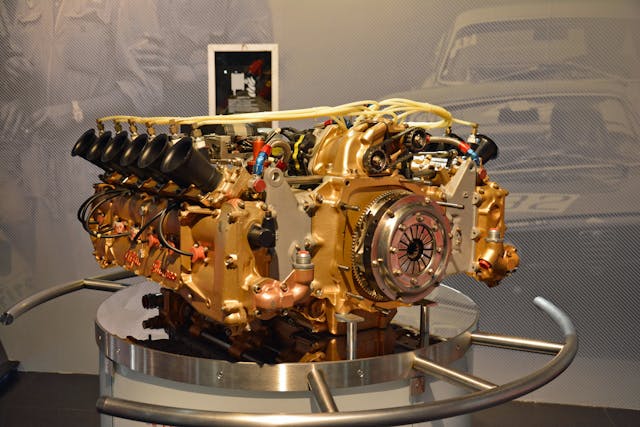

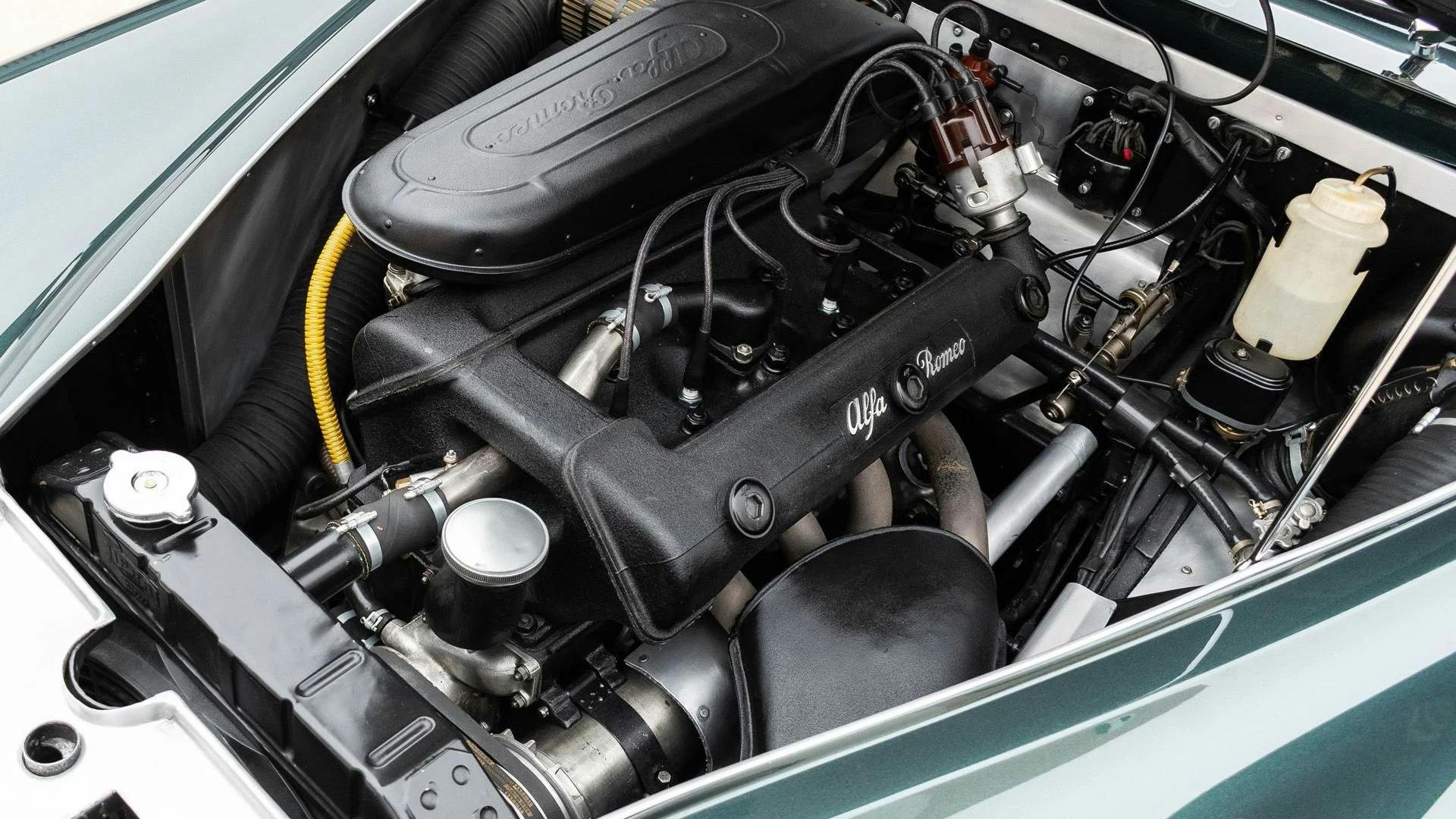

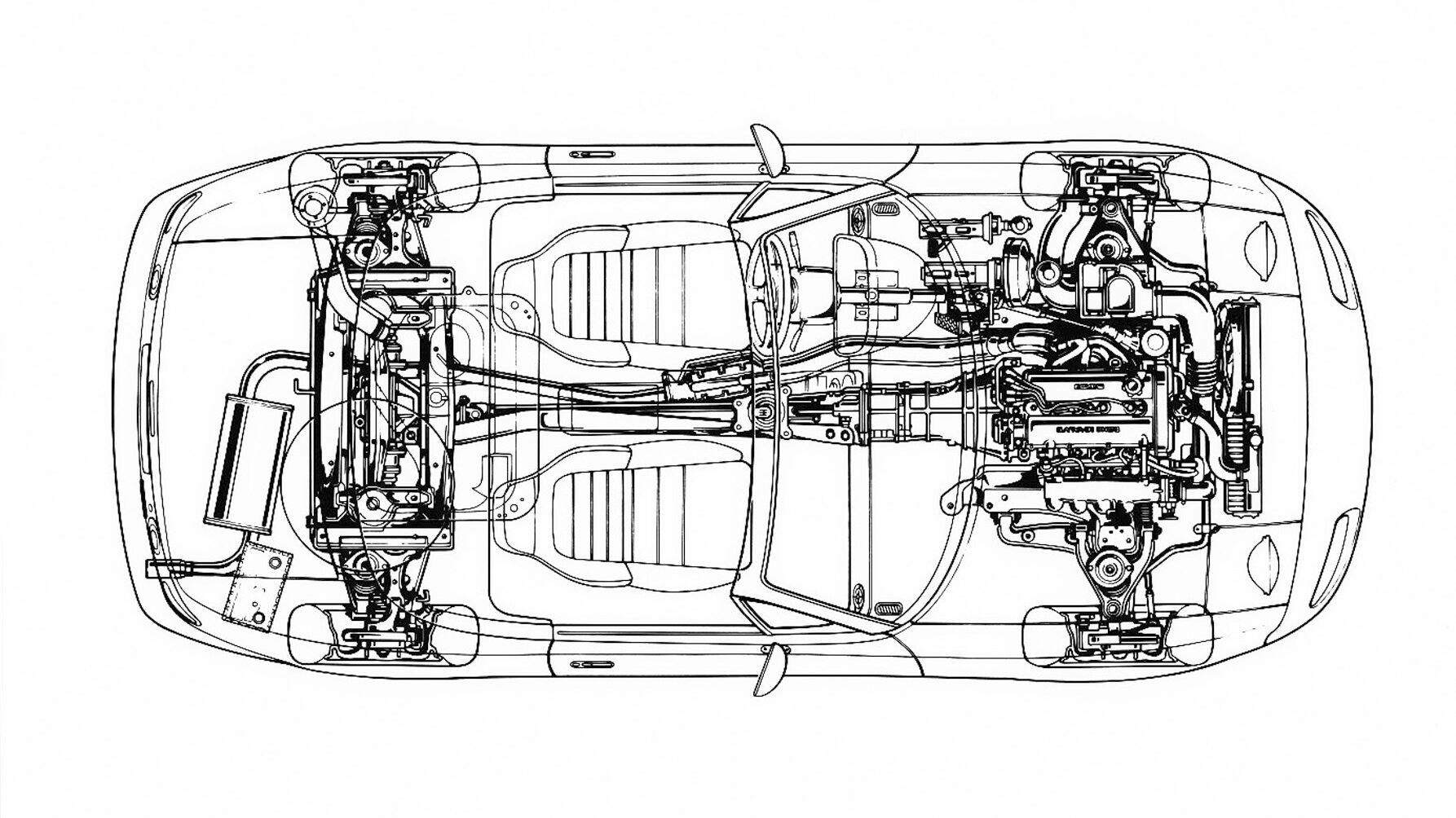

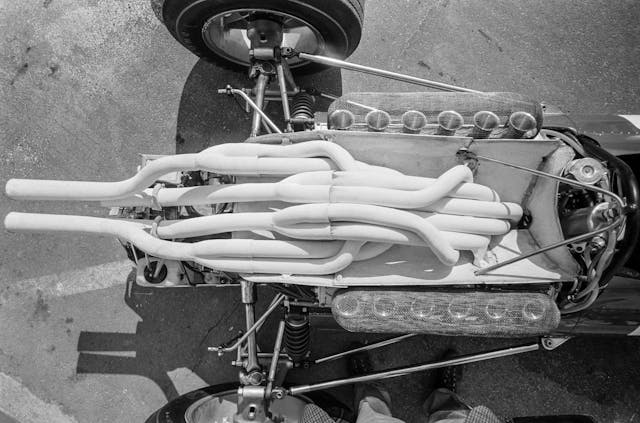

The heart of the Biturbo, and the origin of its name, is a screaming overhead-cam V-6 with twin turbochargers.

Unfortunately, the 1984-1986 Biturbos sold on our side of the Atlantic used a blow-through fuel-delivery system featuring a Weber carburetor inside a pressurized box, with no intercoolers. Forced induction systems with carburetors never did prove very reliable for daily street use, and the carbureted/non-intercooled Biturbo proved to be a legend of costly mechanical misery in the real world.

This car came from the factory with both Weber-Marelli electronic fuel injection and an intercooler, rated at 225 horsepower and 246 pound-feet in U.S.-market configuration. This more modern fuel-delivery rig didn’t solve all of the Biturbo’s reliability problems, but it didn’t hurt.

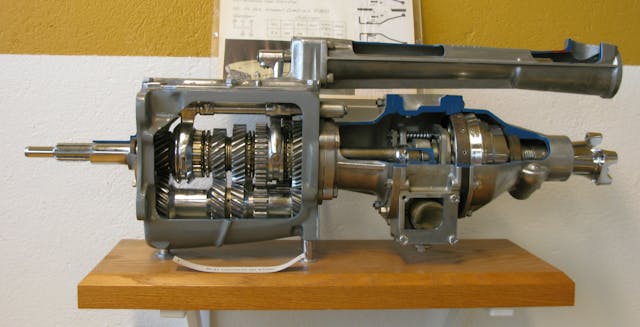

A three-speed automatic was available in the American Biturbo, but this car has the five-speed manual that its engine deserved.

When everything worked correctly, the 1989 Biturbo was fast and decadent, with nearly as much power as a new 1989 BMW M6 for about ten grand cheaper. The Spyder for that year had an MSRP of $44,995, or about $116,500 in 2024 dollars. Sure, a Peugeot 505 Turbo had an MSRP of $26,335 ($68,186 after inflation) and just 45 fewer horses, but was it Italian? Well, was it?

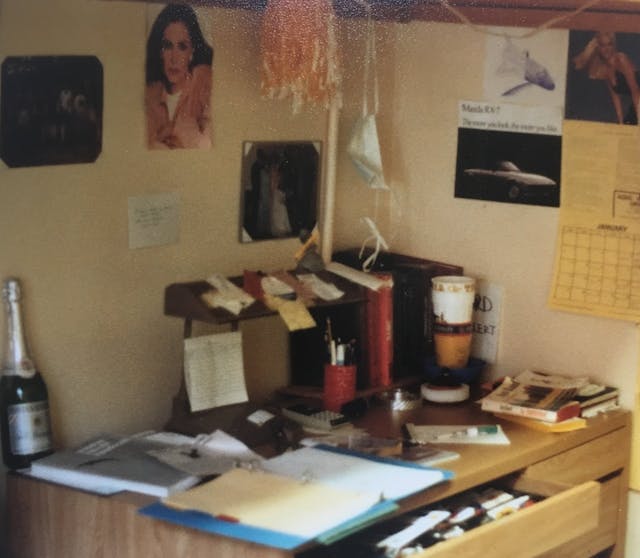

Soon after the time the first Biturbos hit American roads, I was a broke college student delivering pizzas with my Competition Orange 1968 Mercury Cyclone in Newport Beach, California. At that time and place, bent bankers and their henchmen were busily looting Orange County S&Ls, and the free-flowing cash resulted in Biturbos appearing everywhere for a couple of years. Then, like a switch had been flipped, they disappeared.

This car appears to have been sold all the way across the country from Lincoln Savings & Loan, so it doesn’t benefit from that Late 1980s Robber Baron bad-boy mystique.

If you had one of these cars, you had to display one of these distinctive mobile phone antennas on your ride. A lot of them were fake, though.

This car appears to have been parked for at least a couple of decades, so I believe the 28,280 miles showing on the odometer represent the real final figure.

There’s some rust-through and the harsh High Plains Colorado climate has ruined most of the leather and wood inside. These cars are worth pretty decent money in good condition, but I suspect that it would take $50,000 to turn one like this into a $25,000 car.

Still, it has plenty of good parts available for local Biturbo enthusiasts. I bought the decklid badge for my garage wall, of course.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

The post Final Parking Space: 1989 Maserati Biturbo Spyder appeared first on Hagerty Media.

]]>

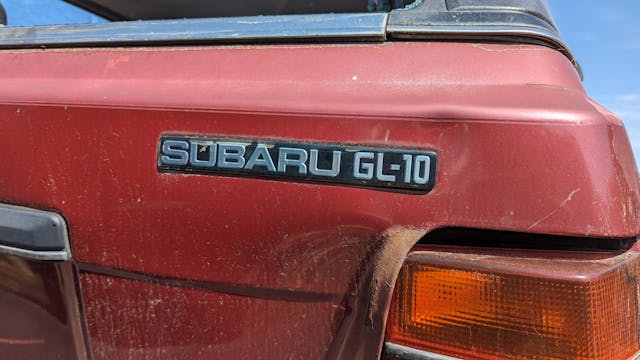

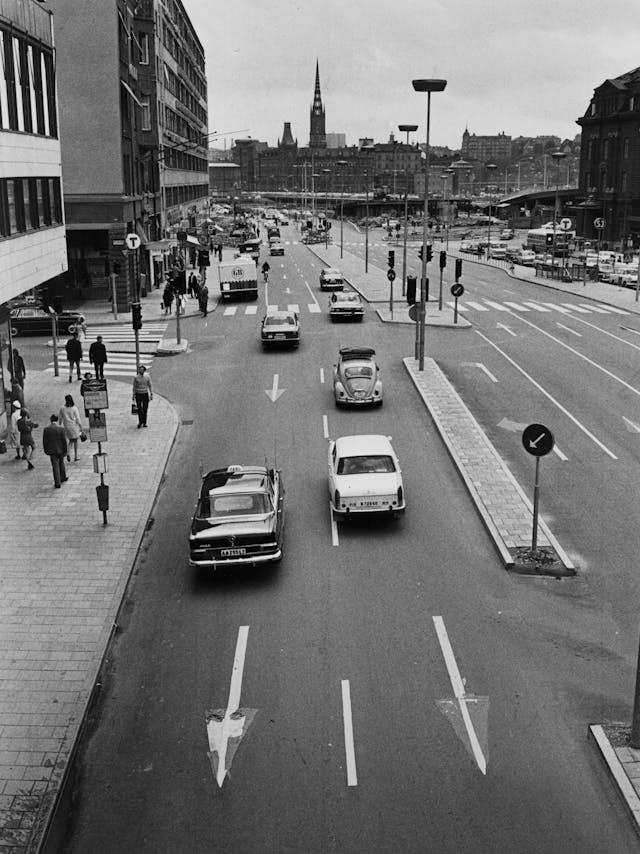

The Type 1 Volkswagen first went on sale in the United States in 1949, and two were sold. After that, VW dealers here did increasingly well with the Type 1—eventually known as der Käfer or the Beetle— with each passing year, with the American Beetle sales pinnacle reached in 1968. These cars have become uncommon in car graveyards in recent years, but I found this fairly solid ’70 in Colorado last winter.

For the 1970 model year, Volkswagen of America offered five models, all built in West Germany: the Beetle, the Karmann Ghia, the Fastback, the Squareback, and the Transporter (which was pitched as the Volkswagen Station Wagon at the time).

The 1970 Beetle was available as a convertible, as a two-door sedan, and as a two-door sedan with sunroof. Today’s FPS car is the latter type, which had a list price of $1929 when new (about $16,001 in 2024 dollars). The non-sunroof sedan cost just $1839 that year ($15,254 after inflation).

The Beetle wasn’t the cheapest new car Americans could buy in 1970, but it was a lot of car for the money. The 1970 Austin America (known as the Austin 1100/1300 in its homeland) had an MSRP of $1815, while American Renault dealers offered a new 10 for a mere $1775. The 1970 Toyota Corolla two-door sedan had an astonishing list price of $1686, which helped it become the second-best-selling import (after the Beetle) in the United States that year, while Mazda offered the $1798 1200 two-door. For the adventurous, there was the motorcycle-engine-powered Honda 600, priced to sell at $1398, and Malcolm Bricklin was eager to sell you a new Subaru 360 for only $1297. How about a 1970 Fiat 850 sedan for $1504? The Ford Pinto and Chevrolet Vega debuted as 1971 models, so the most affordable new American-built 1970 car was the $1879 AMC Gremlin.

The first factory-installed Beetle sunroofs opened up most of the roof with a big sliding fabric cover, but a more modern metal sunroof operated by a crank handle replaced that type for 1964.

The final U.S.-market air-cooled Beetles were sold as 1979 models, which meant that Beetles were very easy to find in American junkyards until fairly deep into the 1990s. You’ll still run across discarded Beetles today, though most of them will be in rough shape and they tend to get picked clean in a hurry.

Volkswagen introduced the Super Beetle, which received a futuristic MacPherson strut front suspension and lengthened snout, as a 1971 model in the United States. Most of the Beetles you’ll find in the boneyards today will be of the Super variety, which makes today’s non-Super an especially good find for the junkyard connoisseur.

I’ve owned a few Beetles over the years, including a genuinely terrifying ’58 Sunroof Sedan with hot-rodded Type 3 engine that I purchased at age 17 for $50 at an Oakland junkyard. It acquired the name “Hubert the Hatred Bug” due to being the least Herbie-like Beetle imaginable. Later, I acquired a 1973 Super Beetle and thought it neither handled nor rode better than the regular Beetle; your opinion of the Super may differ.

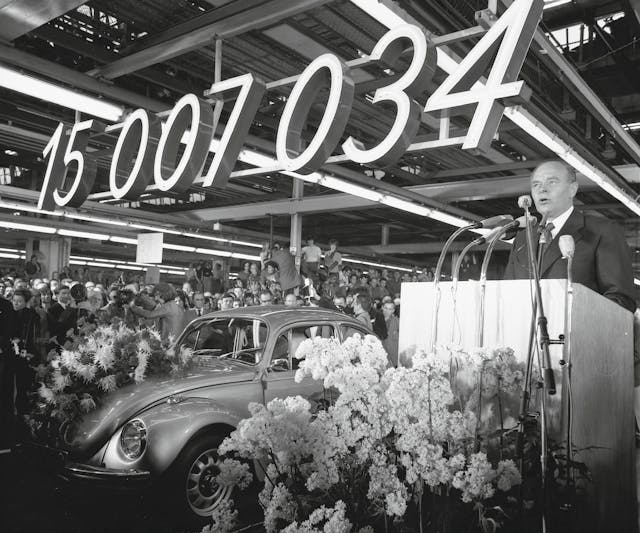

The Type 1 Beetle was obsolete very early on, being a 1930s design optimized for ease of manufacture, but it was so cheap to build and simple to maintain that customers were willing to buy it for decade after decade. Beetle production blew past that of the seemingly unbeatable Model T Ford in 1972, when the 15,007,034th example rolled off the line, and the final Vocho was assembled in Mexico in 2003. That means a last-year Beetle will be legal to import to the United States in just four years!

The first water-cooled Volkswagen offered in the United States was the 1974 Dasher, which was really an Audi 80. It was the introduction of the Rabbit a year later (plus increasingly strict safety and emissions standards) that finally doomed the Type 1 Beetle here; Beetle sales dropped from 226,098 in 1974 to 78,412 in 1975 and then fell off an even steeper cliff after that. For the 1978 and 1979 model years, the only new Beetles available here were Super convertibles.

The original engine in this car was a 1585cc boxer-four rated at 57 horsepower, although there’s plenty of debate on the subject of air-cooled VW power numbers to this day. These engines are hilariously easy to swap and were once cheap and plentiful, though, so the chances that we are looking at this car’s original plant aren’t very good.

This is a single-port carbureted engine with a generator, so it could be the original 1600… or maybe it’s the ninth engine to power this car. Generally, junkyard Type 1 engines get grabbed right away these days, but this car had just been placed in the yard when I arrived.

The hateful Automatic Stickshift three-speed transmission was available as an option in the 1970 Beetle, but this car has the regular four-on-the-floor manual.

To get into reverse, you push down on the gearshift and then into the second-gear position (this can be a frustrating process in a VW with worn-out shifter linkage components).

By air-cooled Volkswagen standards, this car isn’t especially rusty. I’m surprised that it ended up at a Pick Your Part yard, to be honest… and now here’s the bad news for you VW fanatics itching to go buy parts from it: I shot these photos last December and the car got crushed months ago. I shoot so many vehicles in their final parking spaces that I can’t write about every one of them while they’re still around.

It even had the original factory Sapphire XI AM radio.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

The post Final Parking Space: 1970 Volkswagen Beetle Sunroof Sedan appeared first on Hagerty Media.

]]>

The American Motors Corporation did good business selling small, sensible cars bearing the Rambler brand during the late 1950s through early 1960s. Rambler sales peaked in the 1962 model year, after which competition from new compact and midsize offerings from the Detroit Big Three made life tougher for the not-so-big Kenosha outfit. During the middle 1960s, AMC battled for midsize sales against the likes of the Chevrolet Chevelle and Plymouth Belvedere with its Rambler Classic. Today we’ll admire the first AMC product in this series with a Classic 660 found in a yard located between Denver and Cheyenne.

The Classic began life as a 1961 model during George Romney’s reign at AMC, then got a complete redesign for 1963 and became bigger and more modern-looking. Unfortunately for AMC, Ford introduced the Fairlane as a 1962 model, while Chrysler was right there with brand-new B-Body midsize machinery at the same time. As if that wasn’t enough, GM stepped up with the Chevelle and its A-Body siblings for the 1964 model year.

AMC, by then without Romney (who had gone on to become governor of Michigan), completely redesigned the Classic for 1965 and it looked just as slick as its many rivals. The following year, the Rambler name entered a phase-out period that was completed when the final AMC Ramblers were sold as 1969 models (the last year for Rambler as a separate marque was 1968).

The 1965 Classic was a bit smaller than the Fairlane, Chevelle, and Belvedere, though somewhat bigger than the Commander from soon-to-be-gone Studebaker.

The ’65 Classic offered plenty of value per dollar; the list price for this car would have been $2287 (about $22,894 in 2024 dollars). Its most menacing sales rival was the Chevelle Malibu, which had an MSRP of $2299 ($23,105 in today’s money) with roughly similar equipment.

This car is a 660, which was the mid-priced trim level slotted between the 550 and 770. Rambler shoppers who wanted to pinch a penny until it screamed could get a zero-frills Rambler 550 two-door sedan for just $2142 ($21,443 after inflation), which just barely undercut the cheapest Ford Fairlane Six ($2183) and Chevelle 300 ($2156) two-door sedans. Studebaker would sell you a new Commander two-door for a mere $2125 that year, but found few takers for that deal.

The 1965 Classic’s light weight (curb weight of 2882 pounds for the 660 four-door) made it respectably quick even with a six-cylinder engine. This car was built with an AMC 232-cubic-incher rated at 145 horsepower. If you wanted a genuine factory hot rod Classic for ’65, a 327-cubic-inch V-8 (not related to Chevrolet’s 327) with 270 horses was available.

But back to the straight six: This incredibly successful engine family went on to serve American Motors and then Chrysler all the way through 2006, when the final 4.0-liter versions were bolted into Jeep Wranglers. The 232 was used in new AMC cars through 1979.

Automatic transmissions were very costly during the middle 1960s and the Classic didn’t get a four-on-the-floor manual transmission until 1966, so the thrifty original buyer of this car went with the base three-speed column-shift manual.

At least it has a factory AM radio, a $58.50 option ($586 now).

You had to pay extra to get a heater in the cheapest 1965 Studebakers, but a genuine Weather Eye heater/ventilation system was standard equipment in every 1965 Rambler Classic.

AMC sold more than 200,000 Classics for 1965, and the most popular version was the 660 sedan. I still find Classics regularly in car graveyards, so these cars aren’t particularly rare even today.

This one is just too rough and too common to be worth restoring, but some of its parts should live on in other Ramblers.

Its final parking space has it right next to another affordable American machine that deserved a better fate: A 1979 Dodge Aspen station wagon.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

The post Final Parking Space: 1965 Rambler Classic 660 4-Door Sedan appeared first on Hagerty Media.

]]>

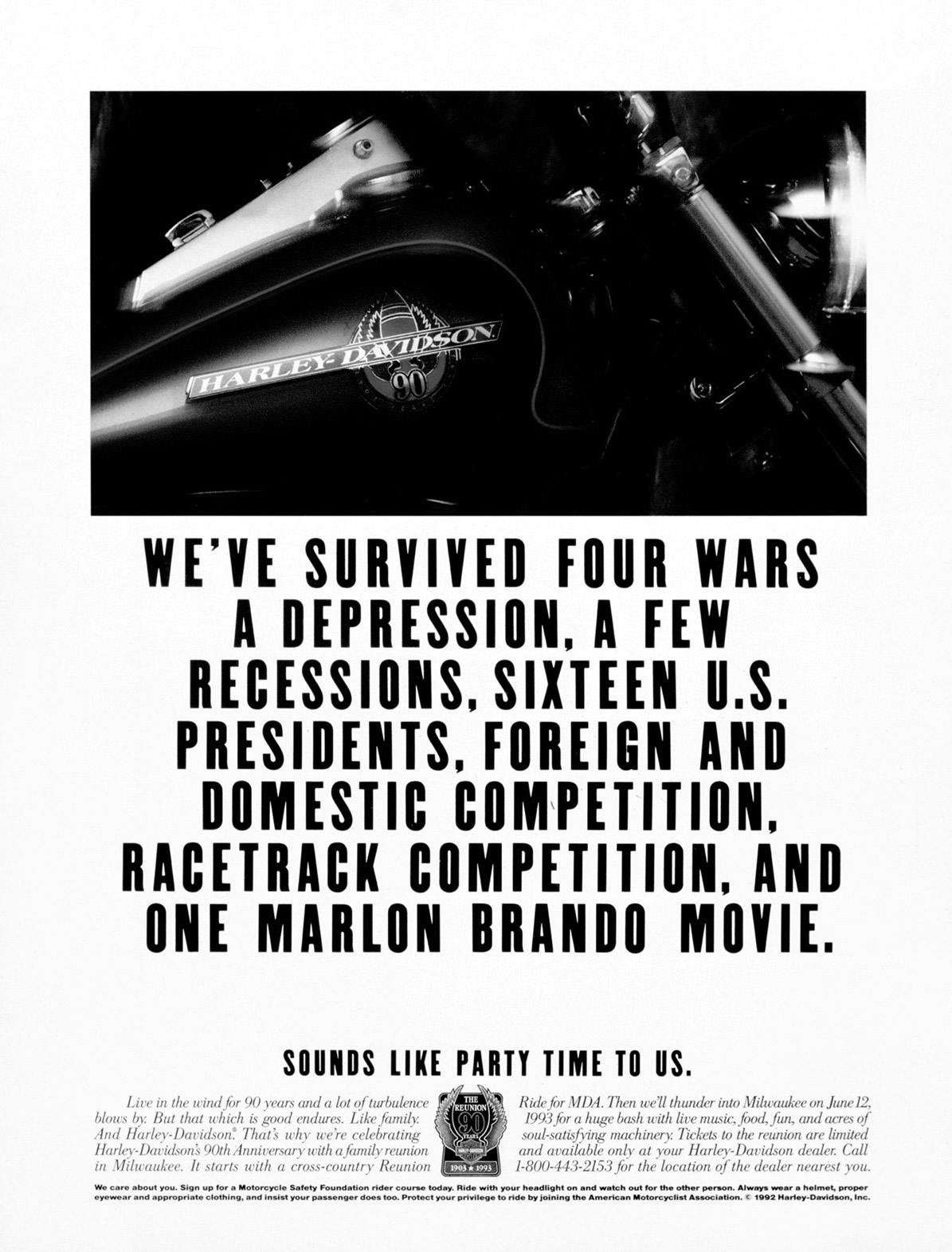

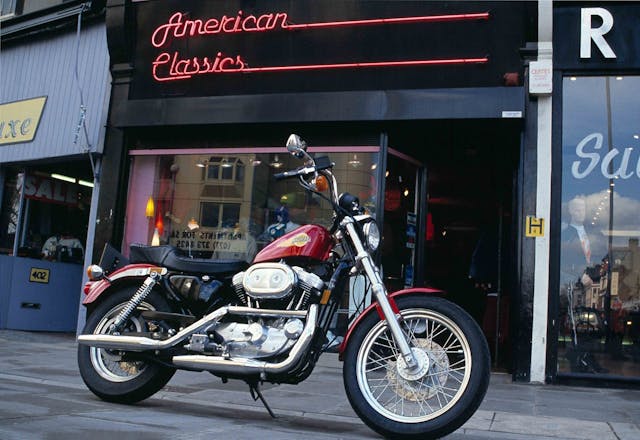

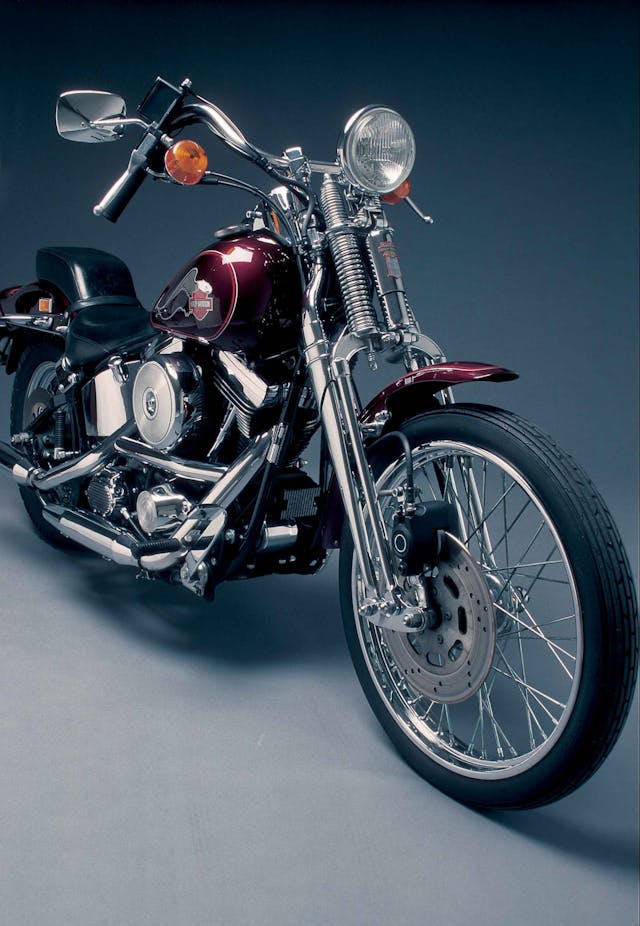

Four decades on from its launch, Harley-Davidson’s original FXST Softail is not a bike that would stand out in most crowds. It’s a simply styled cruiser with raised handlebars, a thick dual seat, and an air-cooled V-twin engine with cylinders set at the Milwaukee marque’s traditional 45-degree angle.

But that first Softail more than justified the swirling dry-ice drama of Harley’s publicity photo. In fact, this relatively restrained 1338cc model is among the most significant in the company’s 121-year history.

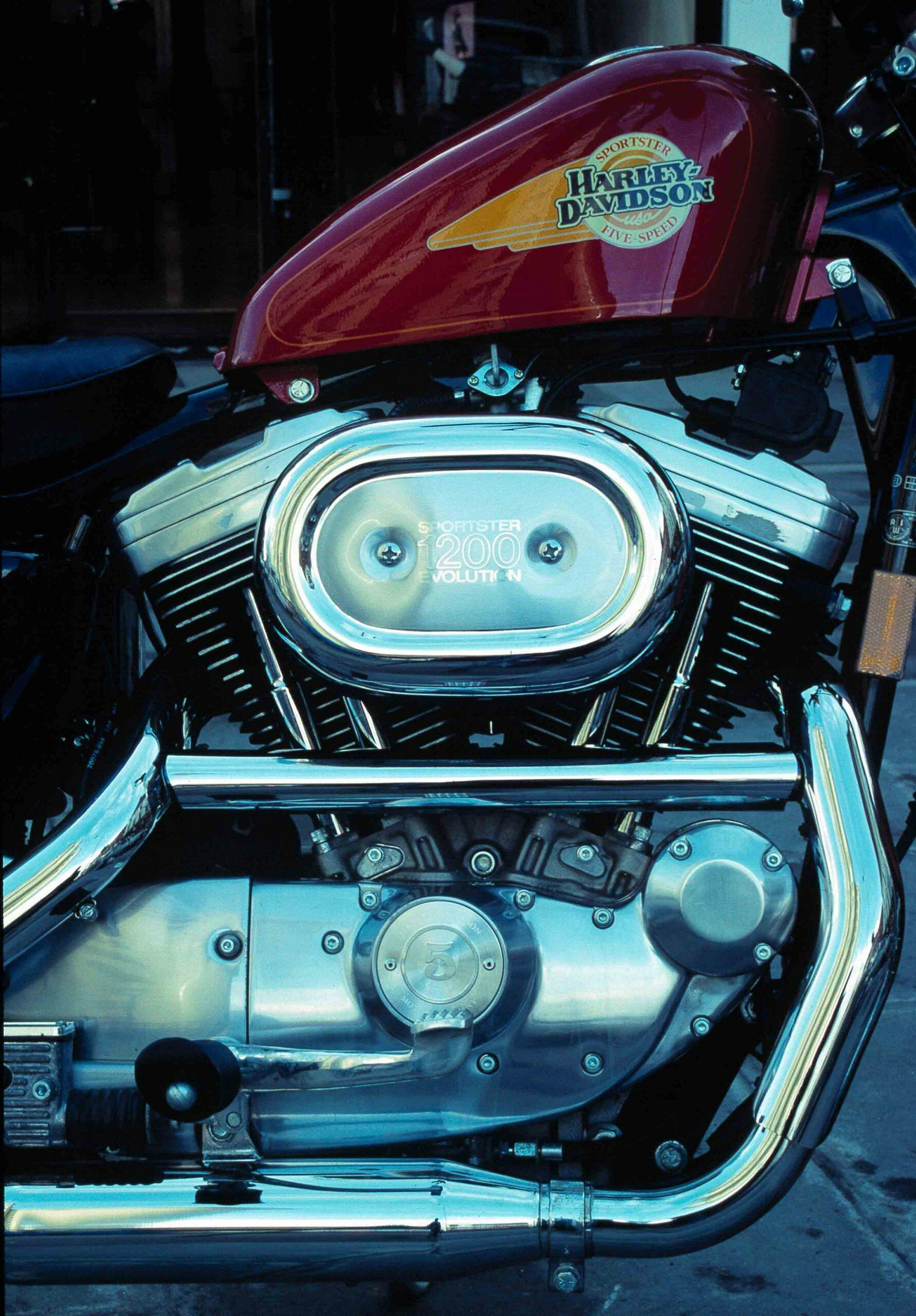

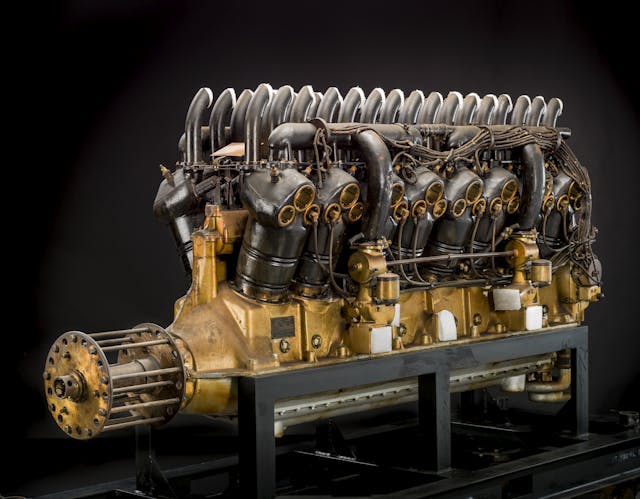

Back in 1984, the Softail was one of the five models fitted with Harley’s Evolution V-twin engine. With its aluminum cylinder barrels and heads, and more importantly its increased performance, cooler running, and much improved reliability over the previous Shovelhead unit, the Evolution brought the ailing firm rumbling out of the dark ages and into the light.

The FXST offered an additional attraction with its chassis. Its Softail name highlighted the new steel frame whose hidden suspension units cleverly allowed a comfortable ride while giving the impression of an old-style “hardtail” rear end. Before long, there would be a whole family of Softails.

Most importantly of all, the Evo-engined models appeared at a pivotal time, like a cavalry division charging over the horizon just as the surrounded soldiers with their antiquated rifles were facing slaughter.

Harley-Davidson’s situation in 1984 was dire. The firm has had well-documented worries in recent years, what with an aging customer base and production falling below 200,000 units from a 2006 peak of almost 350,000. To put that into context, however, things were rough for the company at the dawn of the 1980s, too. While Harley engineers had been finalizing development of the Evolution engine in 1982, production had been less than 25,000. This was below the threshold set by its financial backers, who were entitled to foreclose at any time. The financially strapped company had recently laid off 40 percent of its workforce and cut the salaries of those who remained.

The U.S. motorcycle market had plunged in the late 1970s, unheeded by both Harley and the Japanese manufacturers, who had continued to increase production until they had warehouses full of bikes that could not be sold, even at a discount. Worse still for Harley, its owners AMF (American Machine and Foundry) had boosted production by compromising on quality. By 1984, the result was unreliable bikes, dissatisfied customers, and unhappy dealers faced with increasing warranty work. The firm’s reputation was arguably at an all-time low.

At least there were some positives. Back in 1976, Harley executives had drawn up a long-term plan based on two powertrains: an updated aircooled V-twin, which they called Evolution; and a liquid-cooled family of V-configuration engines, named Nova.

Development of both began the following year, with the Evo project in-house, and Nova contracted out to Porsche Design because Milwaukee lacked the resources to do both simultaneously. In 1981, financial constraints meant that only one project could continue, and the Evolution was chosen.

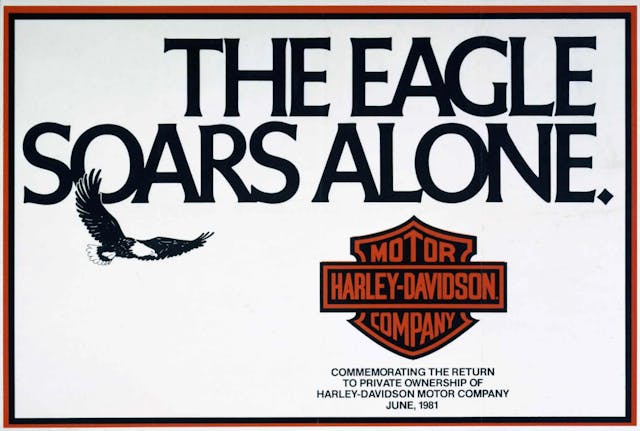

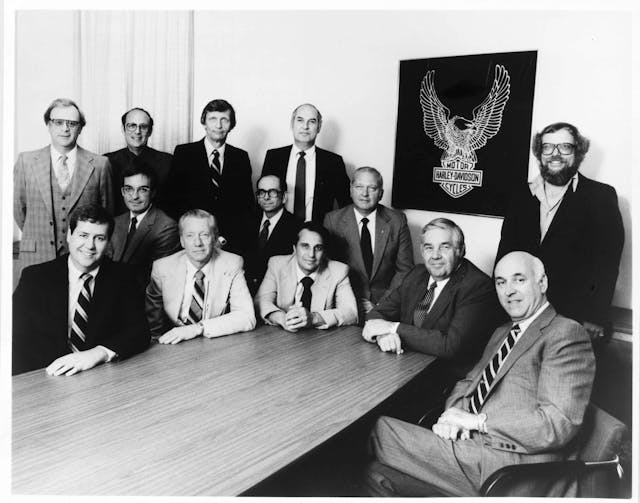

By this time, however, Harley-Davidson was a very different company. A management buyout earlier that year had seen a group of 13 senior executives, led by Vaughn Beals and including styling chief Willie G. Davidson, raise over $80 million to take control from AMF. “The Eagle Soars Alone,” ran the celebratory advertising, but the company remained in a desperate position.

The Evolution engine had been slated for introduction with the 1983 model year, but there was a distinct possibility that Harley’s banks would pull the plug first. That this didn’t happen was partly due to Beals’ successful petitioning of the International Trade Commission to put tariffs of 45 percent on Japanese motorcycles of over 700cc.

President Ronald Reagan signed the tariffs into law in April 1983, but that was far from the end of Harley’s problems. Beals and engineering chief Jeff Bleustein regarded restoring the brand’s former reputation for reliability as so vital that the Evo motor’s introduction was delayed by a year to allow further development.

“I don’t think we ever made a tougher decision,” Beals later said. “The market was terrible, which meant we needed the engine sooner rather than later… But the one vow we took, because of the reputation we had, was that when the Evolution engine came out it would be durable, oil-tight, and bulletproof. We finally decided that the 1983 introduction was too risky, because we weren’t yet confident that it was bulletproof.”

The extra time was well spent. Harley’s engineers continued their more than 5000 hours of dyno testing, redesigned some parts, and refined manufacturing processes. Development riders added to a reported total of 750,000 miles of endurance road work and high-speed laps at the Talladega Superspeedway in Alabama.

The result justified that cautious approach. The Evo engine retained its Shovelhead predecessor’s 1340cc (80-cubic inch) capacity, its cylinder dimensions, crankshaft, and basic bottom-end layout. But almost everything else was new, including the aluminum head and barrels, smaller valves, narrower valve angle, camshaft profile, stronger connecting rods, flat instead of domed pistons, reshaped combustion chambers, and higher compression ratio.

Performance was significantly improved in every respect. Peak power output was up by ten percent, to 71.5 hp at 5000rpm. Torque improved by 15 percent and moved lower down the rev range. Fuel economy was improved, and weight was reduced by 20 pounds. A comprehensively redesigned lubrication system cured the Shovelhead’s habit of leaking as well as burning oil.

The new engine was nicknamed the Blockhead, extending the line that had begun with Flathead, Knucklehead, and Panhead, but it was more commonly called the Evolution. Either way, it came with a 12-month, unlimited-mileage warranty and was an instant success.

Some U.S. motorcycle magazines had previously been reluctant to test Shovelheads due to their many issues, but response to the Evo models was much more positive. “By now you’ve heard all the rumors and read all the speculation. Stop the presses, it’s true,” reported Cycle World about the Electra Glide Classic, which it described as a “thoughtfully conceived, carefully executed major overhaul that manages to blend the tradition of the past with the ideas of the present, to come up with something that’s both modern yet familiar.”

After riding the Electra Glide in the States, British freelancer Alan Cathcart described the Evo engine in Bike as “a quantum leap forward from the days of the iron jug Shovelhead… a successful amalgamation of traditional values and modern technology, of simple pushrod design and refined execution.”

Cycle magazine was positive about another model, the half-faired FXRT Sport Glide, describing it as a “contemporary motorcycle, albeit a very expensive one, rather than a curious alien from another era… The Evolution indicates that Harley-Davidson is making progress, and at an increasing rate.”

Motorcyclist was similarly impressed by the Sport Glide. “For those who wanted to see if Harley could build a real, honest-to-Davidson 1984 motorcycle, feast your eyes. The ’84 season is here—and Harley is right here with it.”

If the models that gained Evolution engines instead of Shovelhead units all contributed to the fight, it was the all-new FXST Softail that would make the biggest impact. Its hardtail-look rear end had originated with an independent engineer from Missouri named Bill Davis, whose modified Super Glide had caught the eye of chairman Vaughn Beals at a Harley rally.

Beals negotiated to buy the rights, and Willie G. Davidson fashioned a relatively lean and simple cruiser whose rigid-look rear end incorporated a hidden pair of shock units sitting horizontally beneath the engine. The Softail engine was held solidly rather than rubber-mounted as with the other Evo units, and for its first year only it had a four- instead of five-speed gearbox.

The Softail wasn’t the most comfortable or practical of Harley’s 1984 models, and it wasn’t the least expensive, either. But its blend of more up-to-date engineering and determinedly old-fashioned style hit the spot, and it quickly became not only very popular but—even more importantly—very profitable too.

Harley-Davidson wasn’t out of financial trouble just yet, even though the year ended with U.S. sales up by 31 percent to over 38,000 in a market that continued to fall. Domestic sales were up again in 1985, putting Harley second behind only Honda in the 850cc-plus category, but that was the year in which the company came closer than ever, before or since, to going bust.

The problem was that Citycorp, which had previously backstopped the company through the difficult times, had new people in important positions. They decided that another recession was looming—and that Harley, despite the upturn in its fortunes, would not survive it, so Citycorp’s best option was to liquidate the firm.

In March 1985, Harley was given an extended deadline of December 31 to find a new backer or file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. Beals later spoke of “hawking begging bowls round Wall Street” that summer as he and chief financial officer Richard Teerlink struggled to convince potential investors that Citycorp’s pessimism was unjustified.

Finally, with time fast running out and all alternatives exhausted, Beals, Teerlink, and colleague Tom Gelb were introduced to a Harley-riding banker named Bob Koe, of Chicago-based Heller Financial, who set up a meeting with his boss, Norm Blake, on the morning of December 23. Blake listened to their pitch… and turned them down.

Somehow, with the bankruptcy seeming almost inevitable, the Harley trio persuaded Koe to arrange another meeting with Blake that afternoon. They finally agreed a deal, more generous to Heller, which gave Citycorp $49M, and Harley $49.5M of working capital. Even then, holiday season delays meant the final transaction was completed with minutes to spare on December 31.

Harley was saved, and Heller’s confidence would be rewarded as the Milwaukee firm defied the general downturn to begin an astonishing period of growth. In 1986, it matched Honda for big-bike sales. The following year Harley was listed on the New York Stock Exchange, and also petitioned the IRC to end the tariff on Japanese bikes ahead of time. President Reagan visited the factory in York, Pennsylvania, to offer congratulations.

A succession of Evolution-engined models powered the recovery. The FLST Heritage Softail of 1986 featured a fat front end inspired by the Hydra-Glide of the 1950s. The Low Rider Custom had a skinny 21-inch front wheel, high bars, and lots of laid-back attitude. In 1988, the FXSTS Springer Softail went further back through time with its updated version of an old-style springer front suspension system.

The Sportster family was also updated with Evolution engines, starting in 1986 with an entry-level model in traditional 883cc capacity, followed soon after by a similarly styled 1100cc variant. Both were popular, the smaller model boosted by Harley’s innovative offer to repay the full $3995 price if its rider traded up to a big twin within two years.

In 1990 came the unmistakable FLSTF Fat Boy, with disc wheels, industrial look, and silver finish with yellow detailing. A year later it was followed by the Dyna Glide Sturgis, named after the South Dakota rally that had become an August fixture for a growing legion of Harley riders.

Willie G’s final Evolution-powered project was one of his finest: The FLTR Road Glide of 1998 featured a frame-mounted fairing and a long, low look that would remain popular for more than two decades. A year later, the Glide and most other Big Twins were fitted with the new Twin Cam 88 engine, a bigger, more powerful V-twin that was another step forward.

The Evo unit continued to power some Softail models for a couple more years, along with the hotted-up, limited-edition FXR Super Glide variants that began the Custom Vehicle Operations line in 1999 and 2000. By this time, Harley’s total production was nudging 200,000. Revenue was close to $3 billion, and profit almost $350 million, the company having set new records for 15 consecutive years.

The Evolution engine, it’s fair to say, had proved a considerable success.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

The post How the Evolution Saved Harley-Davidson appeared first on Hagerty Media.

]]>

Last week, we admired a majestic 1984 Mercedes-Benz S-Class in a Colorado car graveyard, adding to a collection of Final Parking Space machines from (West) Germany that includes BMW, Volkswagen, and Ford-Werke. Plenty of lesser-known German manufacturers have sold cars in the United States, of course, and today we’ve got a discarded example of one of the best-looking cars to come out of Bremen: a Borgward Isabella Coupé, photographed in a self-service yard just south of Denver, Colorado.

Carl Borgward came up in the Bremen car industry, rising through the ranks at Hansa-Lloyd and selling cars badged with his own name starting in 1924. After World War II, he began building Lloyds, Goliaths, and Borgwards, with the Borgward Hansa his first postwar model.

In 1954, the Isabella replaced the Hansa, though Hansa Isabella badging was used for a while.

The Isabella sedan came first, followed by convertible and wagon versions in 1955. The Isabella Coupé appeared in 1957, and production continued in West Germany until the company went (controversially) broke in 1961. Borgward production using the old tooling from the Bremen plant resumed in Monterrey, Mexico, in 1967 and continued through 1970.

The Isabella sold reasonably well in the United States, considering the obscurity of the Borgward brand here. For the 1959 model year, just over 7500 cars were sold out of American Borgward dealerships.

The U.S.-market MSRP for a 1959 Isabella Coupé was $3750, or about $40,388 in 2024 dollars. The base 1959 Porsche 356 coupe listed at $3665 ($39,472 after inflation), while a new 1959 Jaguar XK150 coupe cost $4500 ($48,465 in today’s money).

Meanwhile, GM’s Chevrolet division offered a new 1959 Corvette for just $3,875 ($41,734). The Isabella Coupé faced some serious competition in its price range.

These cars haven’t held their value quite as well as the 356 or Corvette (though nice ones do change hands for real money) and restoration parts are tougher to source, so there are affordable project Isabella Coupés out there for the adventurous. A 24 Hours of Lemons team found this ’59 and raced it several times with the original drivetrain, winning the coveted Index of Effluency award in the process.

Not bad for a race car with 66 horsepower under the hood… 60 years earlier.

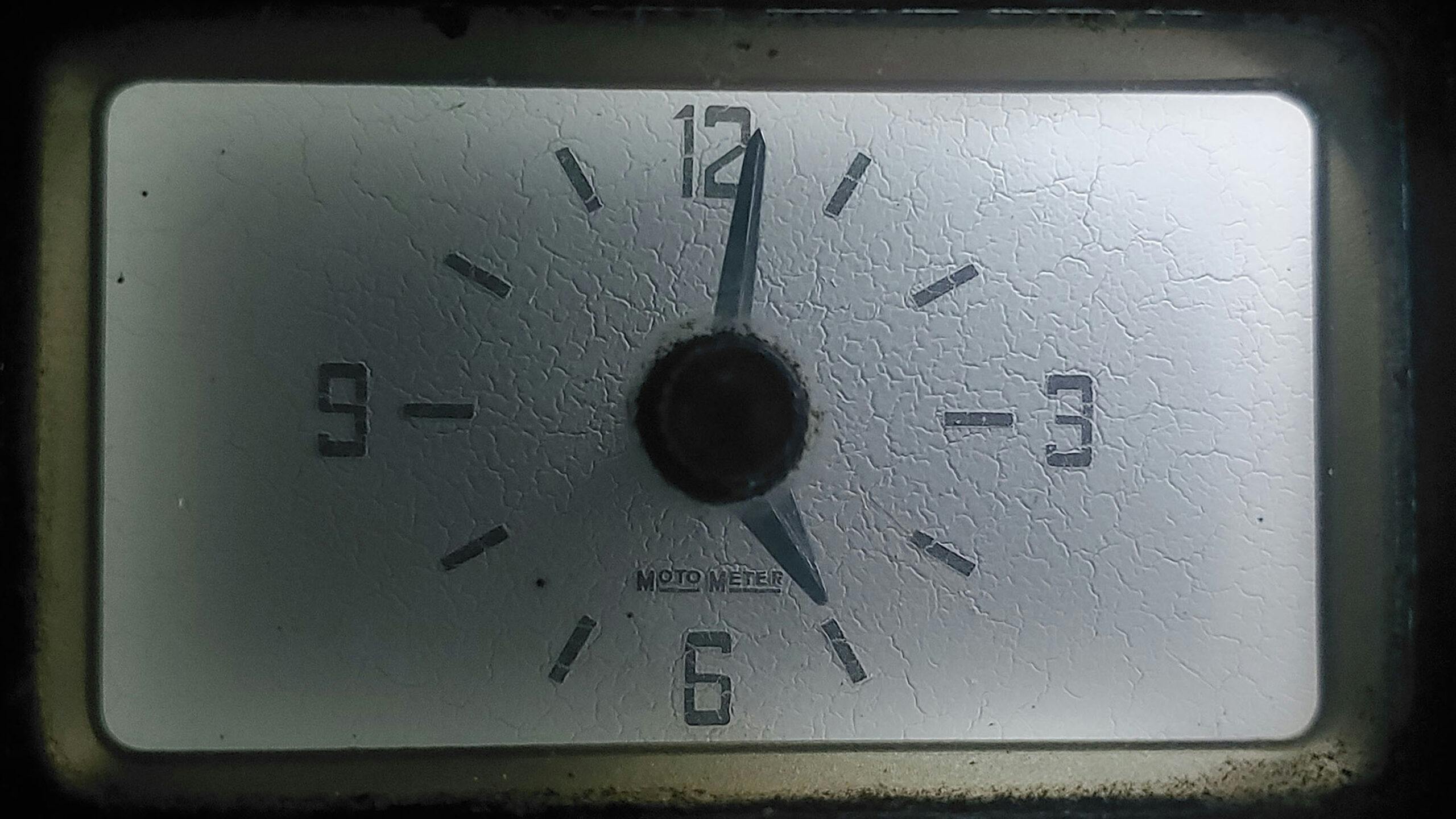

The Fistful of Cotter Pins team members were kind enough to give me the MotoMeter dash clock out of their race Borgward. The mechanism is bad but the face still looks good when illuminated in my garage.

The clock in this car has experienced too many decades outdoors in the harsh climate of High Plains Colorado to be worth harvesting for my collection.

The engine in this car is a 1.5-liter overhead-valve straight-four with a distinctive carburetor location atop the valve cover.

The transmission is a four-speed column-shift manual.

The odometer shows 55,215 miles, and that may well be the actual final total.

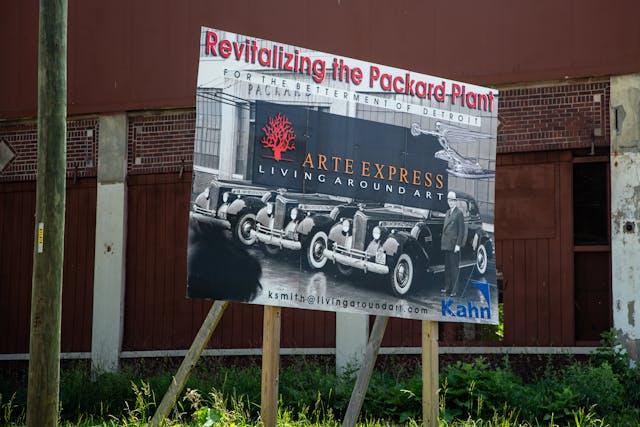

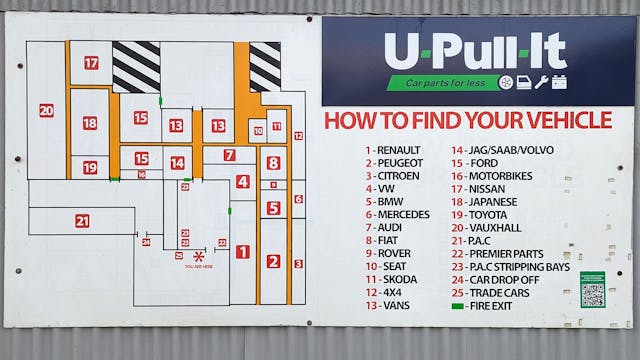

This car was in the Colorado Auto & Parts “private reserve” yard, off-limits to customers for many years. Then that lot was sold, and many of its former inhabitants were moved to the regular U-Pull section. We’ve seen some of those cars in earlier episodes of this series, including a 1958 Edsel Citation, a 1963 Chevrolet Corvair Monza, and a 1963 Chrysler Newport sedan.

The good news about this car is that CAP will sell you the whole thing, being a non-corporate yard owned by the Corns family since the late 1950s. You’ll be able to check out the famous radial-engine-powered 1939 Plymouth, built on the premises, in the office when you visit.

This car appears to be a bit too rough to be economically viable as a restoration, but there are still plenty of good parts to help fix up nicer Isabellas. Or you could make a race car out of it, which we recommend.

I like to use ancient film cameras to shoot junkyard vehicles, and I took a few photographs of this car (and many others) with a 1920s Ansco Memo.

This double exposure (always a hazard with century-old cameras) came out looking interesting, and the Isabella was an appropriate subject.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

The post Final Parking Space: 1959 Borgward Isabella Coupé appeared first on Hagerty Media.

]]>

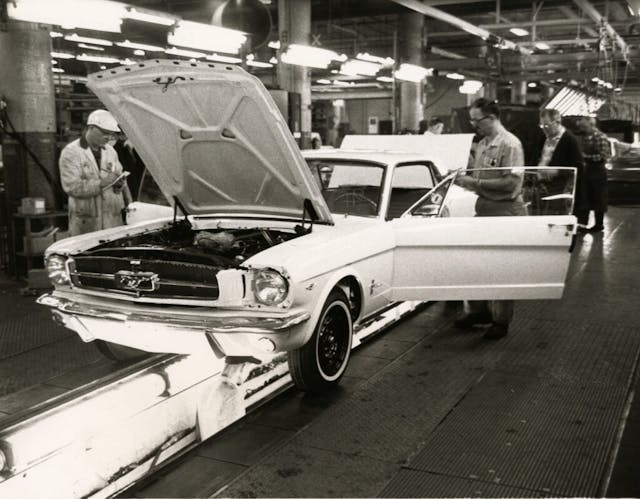

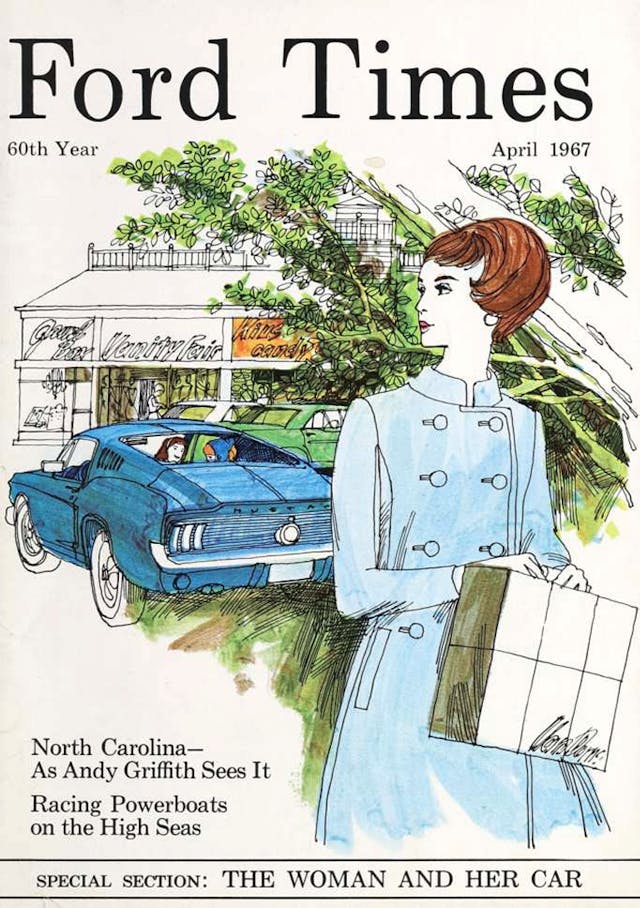

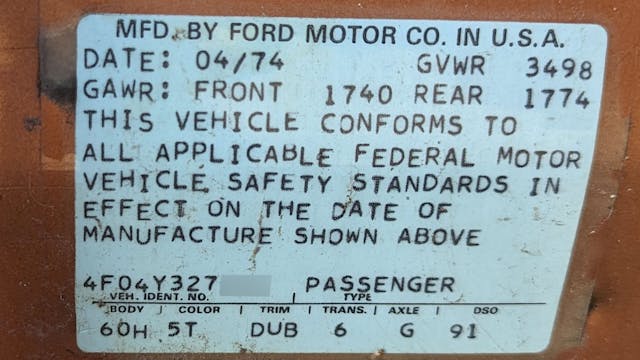

April 17 marks sixty years since the Ford Mustang’s public debut at the 1964 New York World’s Fair. The original pony car immediately became a pop-culture and automotive phenom, and it remains one of the most impactful cars in history. We’re celebrating with stories of the events surrounding the Mustang’s launch, the history of the early cars, and tales from owners. Click here to follow along with our multi-week 60 Years of Mustang coverage. —Ed.

The beauty of celebrating an automotive icon like the Ford Mustang is there are more historic moments to commemorate and significant places to visit than there are candles on the pony car’s birthday cake. As the Mustang turns 60 on April 17, enthusiasts have plenty of opportunities to pay proper homage.

Of course, there are many impressive museums out there to whet your Mustang appetite—including The Henry Ford, the Gilmore Car Museum, the Mustang Owners Museum, and the Mustang Museum of America. And the Flat Rock Assembly Plant, which manufactures current Mustangs, offers a potential photo op with your ride (although the last time we checked there were no tours).

If you’re looking for something a little different, however, here are some suggested destinations where Mustang history was made. Some of them don’t look like they used to, so keep an eye out for ghosts of Mustangs past.

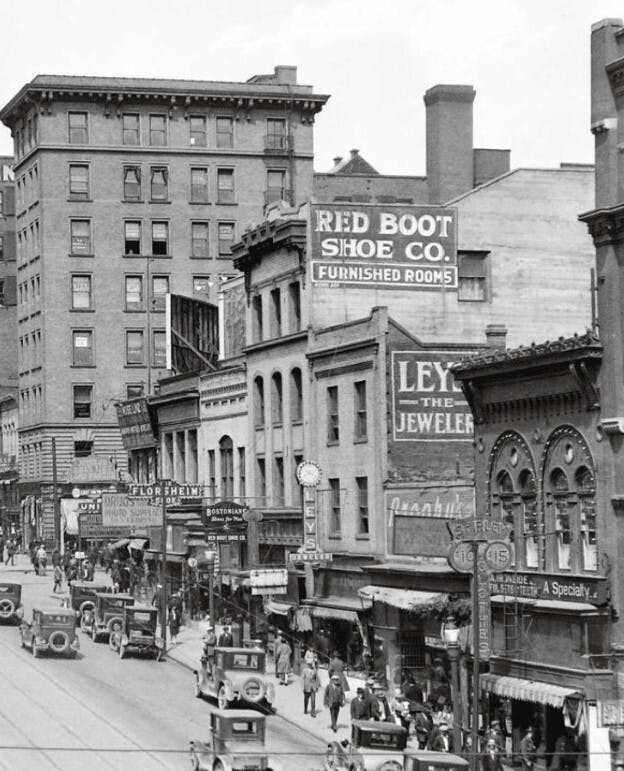

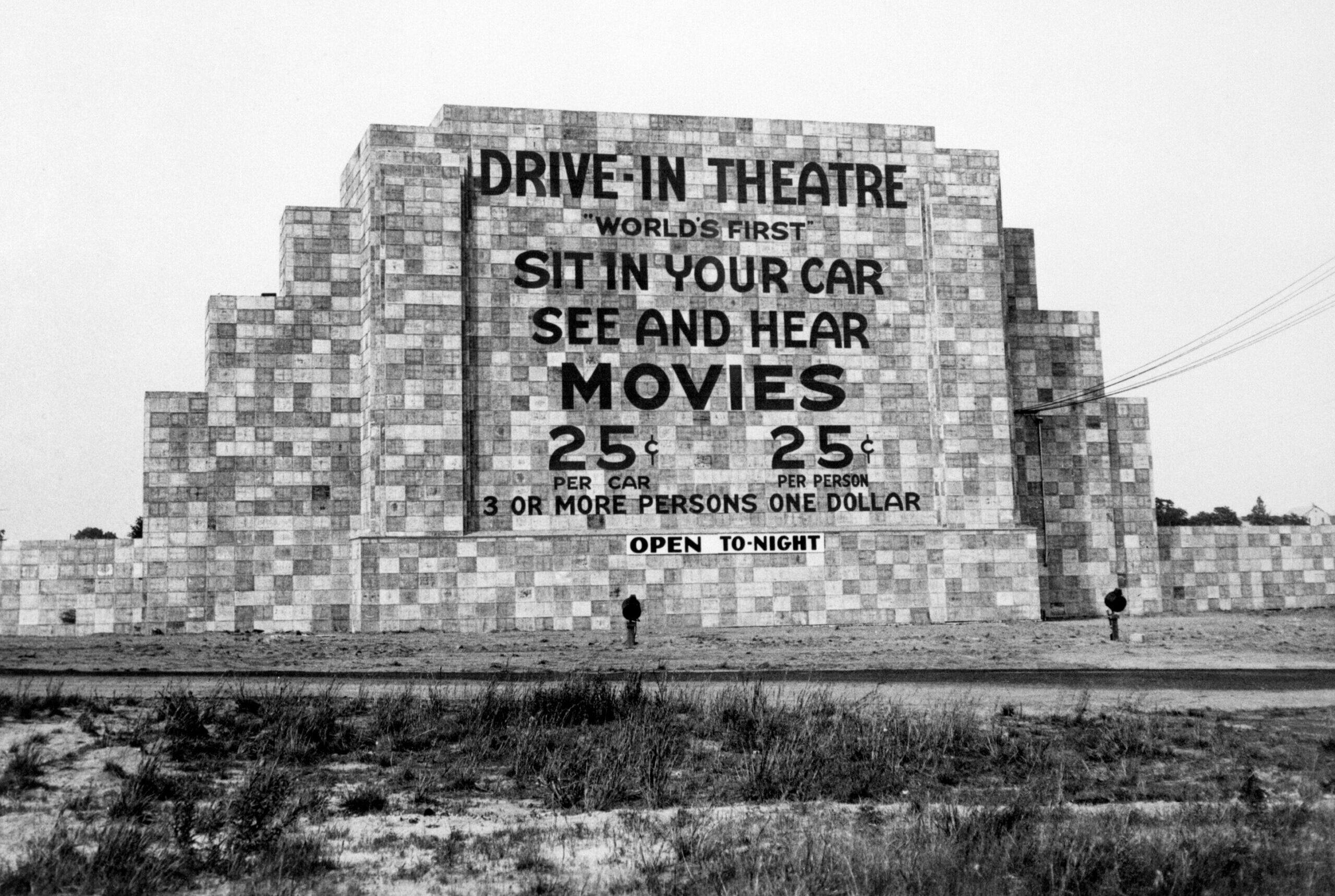

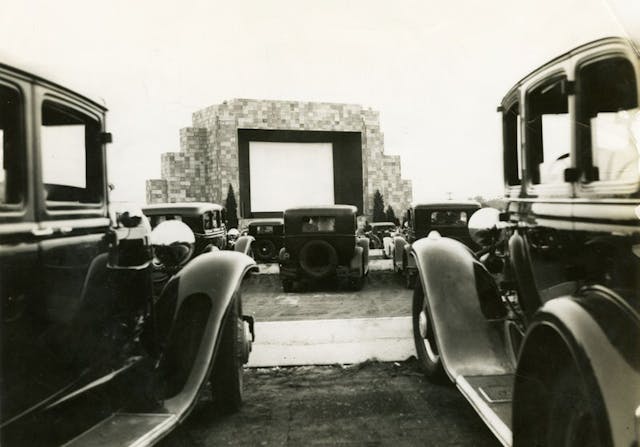

1964–65 New York World’s Fair site

Although the public unveiling of the Mustang was held on April 17, 1964—which is considered the official birthdate of the car—members of the press were given a sneak peek three days earlier. Both showings were held in front of the Ford Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair. Although the Fair featured 140 pavilions and 110 restaurants during its two summers at Flushing Meadows Corona Park in Queens, few of the original structures remain. Skeletons include the New York State Pavilion, a pair of towers topped with circular observation platforms (they are no longer operational); the roofless Tent of Tomorrow pavilion; and the iconic Unisphere, a 120-foot-tall stainless-steel globe. (If you’re in the Detroit area, you can get a taste of the ’64–65 World’s Fair by checking out the giant Uniroyal tire that was originally a Ferris Wheel.)

Dearborn Mustang Plant

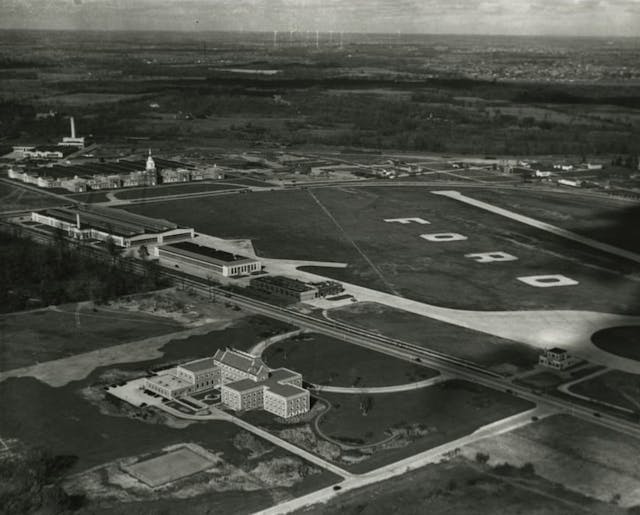

Mustang production began at Ford’s Dearborn Assembly Plant on Miller Road, and although Ford also built Mustangs at facilities in Edison, New Jersey, and San Jose, California, only D.A.P. (as it was often called) was active for four decades. After more than 6.7 million ponies rolled off the line in Dearborn, the final Mustang produced there was completed at 1:07 p.m. on Monday, May 10, 2004.

Riverside International Raceway

Mustangs and motorsports are forever linked, and Mustangs often made history at California’s Riverside Raceway, not only for racing but for vehicle development. Carroll Shelby tested his original Cobras at Riverside, and the 1967 and ’68 Shelby Mustang models were revealed there. In 1970, with Riverside serving as the Trans-American Sedan Series championship finale, Parnelli Jones came back to win in a Bud Moore Ford Mustang, giving Jones the unofficial driver championship by one point. It was the first and only year that every Detroit pony car manufacturer had a factory-backed team in Trans-Am.

Alas, Riverside closed on July 2, 1989 and was bulldozed to make room for a shopping mall that opened in 1992. Riverside’s old administration building remained until 2005, when it was torn down to make way for townhouses. If you’re moved to pay a visit to the former location of the southern California track, the Moreno Valley mall is located at 22500 Town Circle in Moreno Valley, about a half-hour south of San Bernardino.

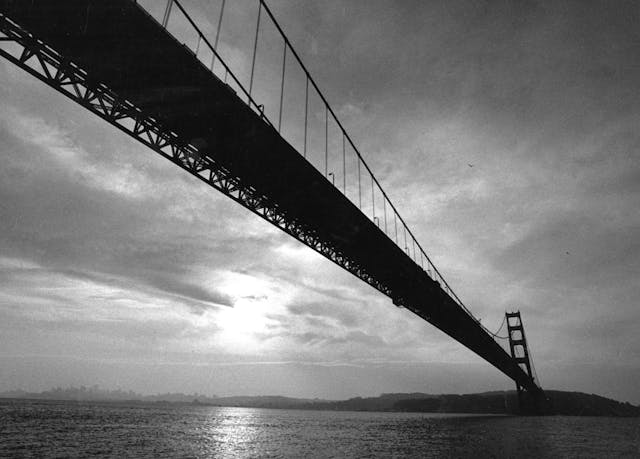

Bullitt movie locations, San Francisco

There may be no more famous Mustang than the 1968 GT390 fastback driven by Steve McQueen in the legendary movie Bullitt. Certainly there’s no Mustang that’s worth more; in 2020, the Highland Green Bullitt car sold for $3.74 million. Many consider the movie’s chase scene the best in film history, and although we don’t encourage any Mustang enthusiasts to recreate that iconic chase, you could—if you really, really wanted to—on the hilly section of San Francisco’s Fillmore Street.

Shelby American at LAX

Carroll Shelby started Shelby American in 1962 and completed the 260 Roadster—later known as the Cobra—soon after. Within a couple of months, Shelby set up shop in Venice, California, and by June 1963 he was being courted by Ford, which was hellbent on beating Ferrari at Le Mans. Shelby succeeded, winning the GT Class at the storied French endurance race the following year, thanks to the Daytona Coupe.

After outgrowing the Venice location, Shelby American moved to a hangar on the south end of Los Angeles International Airport in 1965, and it became the birthplace of the famous Shelby Mustang GT350. Shelby moved his operations again in 1967 after losing his lease at LAX, and today the hangar is home to the Japanese aviation firm Nippon Cargo Airlines.

The Empire State Building

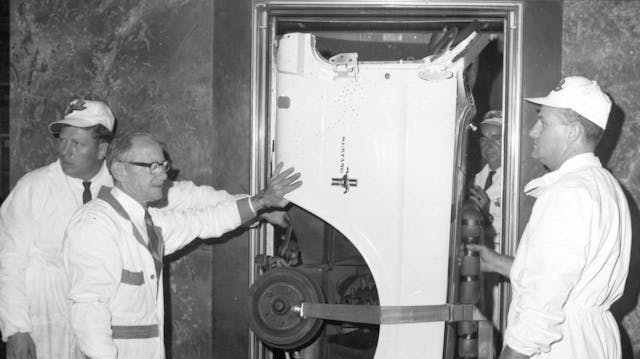

Yes, we’re back in New York, but this is the one site that hasn’t changed much in the last six decades (even if the view has). And the story is so incredible that we had to end with it. In 1965, with the Mustang selling at a record-setting pace in the U.S., the general manager of the Empire State Building—then the tallest building in the world—came up with a big idea. Robert L. Leury wondered if Ford might be interested in displaying a Mustang on the 86th-floor observation deck. As crazy as it sounds, Ford was all in … except its technicians had to figure out how to get a car up there.

A crew of engineers took meticulous measurements (or so they thought) and decided that by disassembling a Mustang into four sections, they could fit everything inside the Empire State Building’s seven-foot tall elevations, then reassemble the car up top. On the night of October 20, 1965, after taking the Mustang apart as planned, the crew discovered that the steering column was a quarter-inch too tall for the elevator. Undeterred, they improvised and made it fit, and the car was completed by the next morning. The Mustang was displayed for five months before it was taken apart and removed. The stunt was recreated with a 2015 Mustang GT to celebrate the Mustang’s 50th anniversary.

Did we miss something cool? Do you know of some historic sites that your fellow Mustang enthusiasts might enjoy visiting? Please let us know in the comments section below.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

The post 6 Historic Mustang Sites That Are Worth a Visit (Just Beware of Ghosts) appeared first on Hagerty Media.

]]>

April 17 marks sixty years since the Ford Mustang’s public debut at the 1964 New York World’s Fair. The original pony car immediately became a pop-culture and automotive phenom, and it remains one of the most impactful cars in history. We’re celebrating with stories of the events surrounding the Mustang’s launch, the history of the early cars, and tales from owners. Click here to follow along with our multi-week 60 Years of Mustang coverage. -Ed.

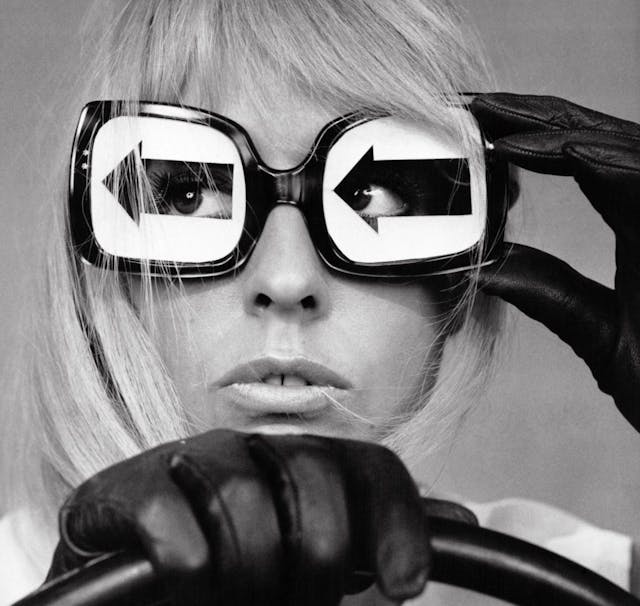

Car people over a certain age certainly remember the April 1964 debut of Ford’s first Mustang. Enthusiasts yawned at first due to the car’s lowly Falcon-based platform and powertrains, but most were eventually charmed by its sporty looks, multiple appealing options, and affordable pricing.

U.S. auto executives outside the Blue Oval wondered whether to take it seriously. Bob Lutz (who would later rise to top leadership levels at Ford, Chrysler, and General Motors) had been working at GM Overseas Operations (GMOO) for a bit more than a year when Mustang was launched. “The clan of car guys l hung out with agreed it was a genius marketing move,” he tells Hagerty. “We didn’t admire it as a car because of its down-and-nasty Falcon architecture, but we agreed it would be a hit. We underestimated how big of a hit, but so did everyone else. Its appeal was NOT to car guys but to average, low-to-middle-income Americans who saw it as glamorous and aspirational.”

Reaction from GM leadership was initially dismissive. According to Lutz, they calculated the entire U.S. auto sales market at the time at 100,000 units. “Let’s say it’s a smash hit and gets 50 percent of that segment. ‘That’s 50,000 units. Why bother?’ They failed to realize that Ford did not intend [the Mustang to be] part of the ‘sports car’ segment but as cheap, sporty, aspirational family transportation. Once they fully grasped what Ford had pulled off, it was all-hands-on-deck, full speed ahead.”

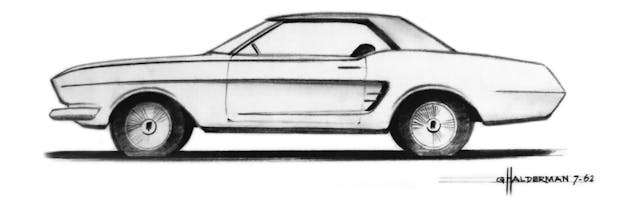

GM and its Chevrolet Division didn’t see that initial ’65 Mustang as a serious threat, but few outside (or even inside) the company knew that Chevy designers had been quietly exploring the same idea of a youthful, sporty compact coupe since soon after the Chevy II debuted for 1962. The project was inspired by the elegant 1963 Buick Riviera “personal coupe” that was launched to take on Ford’s four-seat Thunderbird. Chevrolet styling chief Irv Rybicki wondered whether something similar to the Chevy II in concept but smaller and much more affordable—which could share the Chevy II’s unibody platform and mechanicals—might make sense for Chevrolet. When Rybicki suggested exploring such a car to GM Design Vice President William L. “Bill” Mitchell, Mitchell was intrigued. “By God, that’s not a bad idea!” he reportedly said, “But let’s do it outside the building where no one in the corporation can see what we’re up to.”

“So, we went across the street to our warehouse, created a little room there and started a program,” Rybicki later told us. “And in five months, they had a Chevy II-based clay model dimensionally very close to the future Mustang that no one outside of Ford knew was being developed. But when Rybicki showed it to then-Chevrolet general manager S. E. “Bunkie” Knudsen, Knudsen liked it but decided not to pursue it: “I’ll tell you, fellows,” he said, “one thing we don’t need right now is another car.”

Aside from its popular full-size line, Chevy’s stable at the time included the rear-engine Corvair, the compact Chevy II, the mid-size Malibu, and the Corvette sports car. Rybicki’s proposed sporty compact coupe would add a sixth separate car, and Knudsen didn’t see the need to invest the substantial money, time, and human resources it would take to make that happen.

Rybicki didn’t give up on the idea. Like Ford’s Iacocca, he could see America’s emerging youth market coming. In late 1963, Rybicki had Henry “Hank” Haga’s Chevrolet #2 Studio design a sleek Chevy II-based sporty coupe concept car called “Super Nova.” Mitchell liked it so much that he had it developed into a fiberglass-bodied running car and dispatched it to the April 4, 1964 New York Auto Show, where its appearance two weeks before the Mustang’s April 17 debut at the New York World’s Fair made some Ford folks nervous.

“I recall some of the Ford people coming over while I was standing there and asking whether we were going to build that car,” Knudsen said. “I remarked, ‘If they’ll let us, we’ll build it.’” But when he tried selling it to GM leadership, then-GM president Jack Gordon turned him down.

Camaro/Firebird

When the Mustang bowed to thundering media and public applause, then-Pontiac general manager Elliot M. “Pete” Estes was one GM leader who took it seriously: “I happened to be at Styling when the first Mustang rolled into the garage,” he later recalled. “Everybody was standing around saying what a disaster it was and how market research showed there was no market for it. I didn’t say anything but had a feeling that this thing was going to backfire on us.”

Jerry Palmer, who joined GM Design in 1966 and rose to executive director over all cars and trucks before his 2002 retirement, recalls seeing that first Mustang in its Ford Design studio while still in school at Detroit’s Society of Arts and Crafts (now the College of Creative Studies). “Homer LaGasse, who was on the Mustang design team, arranged a trip for our seniors to go through the studio,” Palmer relates. “The concept was a hot little car, but we were a little disappointed by the actual car.”

Retired GM designer Dick Ruzzin, who had been there for about a year and a half when Mustang was launched, says, on the contrary, that everyone there was surprised. “The design to me was very good as it had some of the character of the recent Lincoln, the sheer slab side and peaked fenders,” he recalls today. “I thought it was a great-looking car, but it was not seen as a performance car in any way. The muscle car era was just beginning, and Mustang responded to that and was part of that movement as it evolved through the years.”

Because the rear-engine compact Corvair was getting a Corvette-look redesign for 1965, GM brass believed that its new style, its bucket-seat Monza coupe and convertible models, and its optional turbocharged engine would help it compete quite well with Ford’s new sporty car. Even Mitchell was telling everyone that the ’65 Corvair was Chevy’s answer to the Mustang.

After Mustang sales topped 100,000 in its first four months alone, with no sign of slowing on its way to the biggest first-year sales success of any new car in history, GM leaders found instant enlightenment. They suddenly decided to hurry up and counter Mustang with the small, sporty coupe and convertible that would become the 1967 Camaro and—partly to appease John DeLorean, who had succeeded Estes as Pontiac general manager and was lobbying hard for a two-seat sports car—a Pontiac variant to be known as the Firebird.

Barracuda/Challenger

Chrysler Corporation actually beat Mustang to market by a couple of weeks with its first Plymouth Barracuda. Believing rumors that Ford was developing a new sporty compact based on its inexpensive Falcon chassis and running gear, Chrysler execs saw an important new market segment and wanted an entry. “Chrysler predicted the ‘specialty compact’ segment would grow to 1.5 million sales by 1970,” Motor Trend reported, “of which it could easily claim 200,000 or more.” With a limited budget, stylist Irv Ritchie sketched the fastback coupe that debuted as a Barracuda option package on the compact Valiant on April 1, 1964.

“The 1964 Plymouth Barracuda was essentially a fastback version of the Plymouth Valiant,” wrote Chandler Stark for musclecarclub.com in 2015, “and it was actually marketed as the Plymouth Valiant Barracuda initially. It used the same wheelbase dimensions and Chrysler A-body platform but with a massive wraparound rear window and taillight … At this stage, the Barracuda was more of a budget car …built for convenience and reliability, not performance.”

That hurry-up car was badly outsold by the Mustang, and it took three years to design and develop the much more competitive second-generation Barracuda for ‘67, which (like the Mustang) offered coupe, convertible, and fastback body styles. Three more years later, Chrysler’s Dodge brand jumped in with its slightly larger, more upscale ‘70 Challenger on an all-new shared platform.

Retired Chrysler Design (and Engineering) vice-president Tom Gale explains that the Mustang arrived a few years before his time there began. “But I was very aware of its impact. For me, the lesson was getting the proportions right, which the Mustang did with its long hood and short deck. The 64-1/2 Mustang, albeit derived from the Falcon, really nailed the proportion with great style and gutsy leadership from Hal Sperlich and Lee Iacocca. Contrast that with the Plymouth Barracuda of the time, where it took until 1967 to make the improved design, which was still based on the A-body Valiant/Dart. But it wasn’t until 1970 with the E-body Barracuda/Challenger that competitors’ cars hit their stride and, in many ways, went beyond Mustang.”

One other Chrysler effort was the original 1966-67 Dodge Charger: a bucket-seat, fastback variant of the mid-size Coronet. Positioned as an upscale “personal luxury” coupe, its targets were much more the Thunderbird, Toronado, and Riviera than the Mustang, and it suffered the same slow-sales fate as AMC’s similar Rambler Marlin.

AMC and the Javelin

Over at the much smaller American Motors, design chief Dick Teague was challenged to design a viable Mustang competitor. A few months before Mustang’s debut, AMC had shown a concept fastback coupe, based on the compact Rambler American, called the Tarpon. Teague wanted to build that car as an answer to Mustang, but then-CEO Roy Abernethy ordered him to upsize that design on the mid-size Rambler Classic platform; that effort became the unlovely Rambler Marlin “personal luxury” coupe. But by mid-1965, Abernethy agreed that the Marlin was a loser, so Tarpon designer Bob Nixon (by then head of small-car exterior design) started work on a replacement initially known as the Rogue, a name AMC was using for its Rambler American hardtop coupe.

Even as the Rogue was taking shape, Chuck Mashigan’s advanced styling studio in October 1965 developed a design study for a Rambler American-based sporty fastback two-seat coupe that Teague named “AMX,” for American Motors Experimental. Teague proposed publicly exhibiting the AMX (which inspired the 1968 two-seat production AMX) and other advanced styling studies to demonstrate that AMC—under new Board chairman Robert Evans—was moving in a new, more youthful direction.

That idea evolved into an impressive “Project IV” traveling show that toured 10 North American cities in 1966, showcasing four concept cars that included the AMX and a longer “AMX II” 2+2 coupe designed by freelance stylist Vince Gardner.

Meanwhile, the production “pony car” project, with styling strongly influenced by the AMX and AMX II, was already under development and would debut (under new Board chairman Roy D. Chapin) as the AMC Javelin for 1968.

The landscape was truly abuzz when the first Mustang hit, an indicator that conditions were ripe for just this type of car. While GM could have fielded a sport-compact Chevy almost immediately after Mustang’s debut but chose to wait and see, Ford had the youthful new market segment practically all to itself (except for that first Valiant Barracuda) from spring ’64 to autumn ’66. By then, GM offered up its ’67 Camaro and Firebird, Chrysler fielded its ’67 Gen 2 Barracuda, and corporate cousin Mercury launched its Mustang-based upscale Cougar. It took another year for AMC to launch its nicely designed ’68 Javelin, and by the time the greatly improved Gen II Camaro, Firebird, Barracuda, and Dodge Challenger arrived for 1970, America’s youthful “pony” and “muscle” car segments were already starting to fade due to safety, emissions, fuel economy, and other government-imposed mandates. It was fun while it lasted.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

The post How GM, Chrysler, and AMC Reacted to the Original Ford Mustang appeared first on Hagerty Media.

]]>

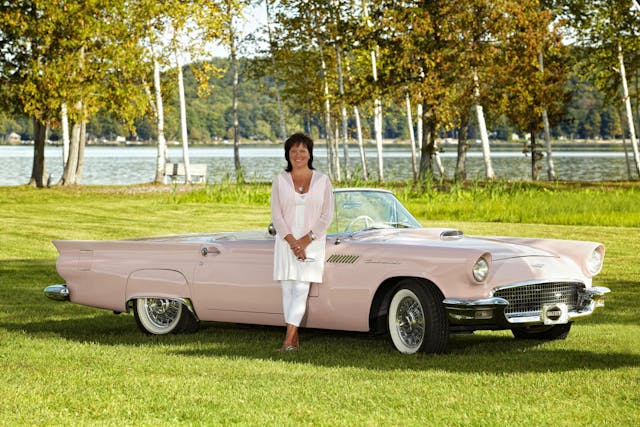

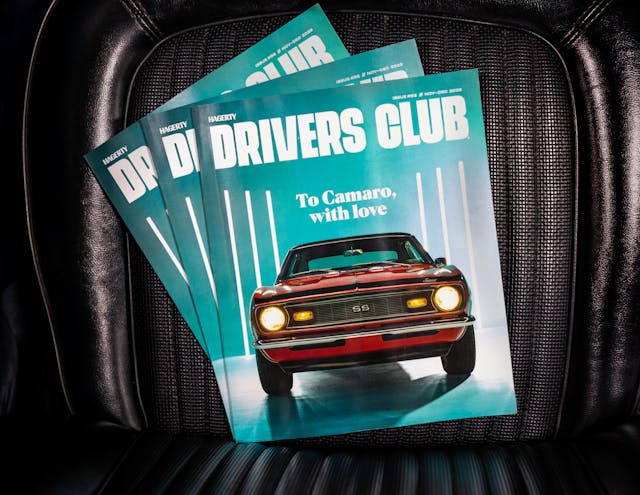

This article first appeared in Hagerty Drivers Club magazine. Click here to subscribe and join the club.

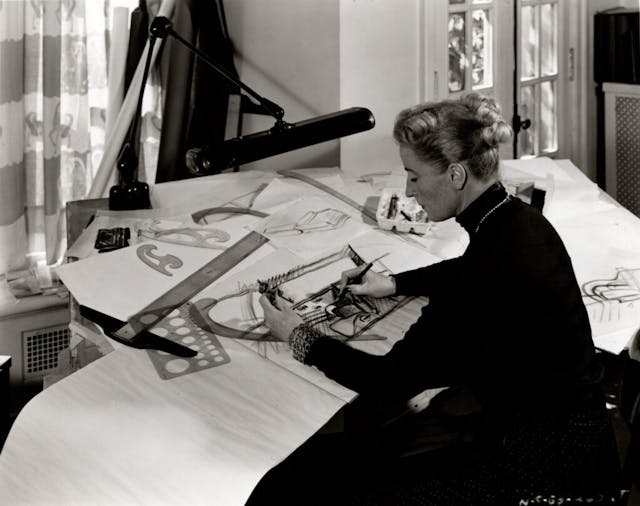

Little Nash Motors up in Kenosha, Wisconsin, came roaring out of World War II with some pretty far-out ideas. Its cars became sleeker and more interstellar, the wheels all but disappearing within wind-smoothed bodywork. The company defied convention by building a premium car that was actually small. The Rambler of 1950 was America’s first legitimate attempt at a compact alternative to the road-conquering Goliaths then in fashion. And Helene Rother, a pioneering female designer whose own story reads like an impossibly dramatic screenplay, played a key role in making it happen.

Rother’s might not be a name with which you’re familiar, but at a time when men universally ruled the auto industry, she was part of a small female vanguard that was destined to quietly put its fingerprints on American car design in the 1940s and ’50s. Notwithstanding her recent induction into the Automotive Hall of Fame, Rother’s achievements are mostly forgotten today. But in an era when small cars were not popular, her interior design for the Rambler was incredibly forward-looking and helped make this car fashionable—and, for a time, successful.

Which is why we took the opportunity to borrow an early Rambler from owner Scott Keesling in Beverly Hills, California, and, er, ramble around the city’s leafy canopied streets for a day. This joyful little car wasn’t made for speedy 0–60 times, nor did it perform aggressively around corners. Its name, Rambler, certainly doesn’t suggest quickness. Instead, it feels genial and easygoing, like spending time on a warm, sun-filled afternoon with an old friend.

***

An unlikely automotive designer, Helene Rother spent her early life a million miles away from Beverly Hills, in Leipzig, Germany, surrounded by books and art. After receiving the equivalent of a master’s degree in 1930 from the Kunstgewerbeschule, an arts and crafts school, in Hamburg, the newly married Rother began a career in visual arts and graphic design. After her daughter was born in 1932, Rother’s husband, a known Trotskyist and a member of various anti-Nazi organizations, soon became persona non grata in Hitler’s Germany and fled to France, leaving Rother and their daughter, Ina, behind.

Rother continued working in design and art, even finding some success in jewelry design before the situation in Germany became untenable. Her connection to her husband put her in danger, and she decided to take her daughter and flee. A group of Americans who had formed the Emergency Rescue Committee shortly after France fell to the Germans sent Rother an alias, counterfeit identification, and $400 to get her to Marseilles. With travel from France to the United States severely restricted, Rother and Ina made their way to Casablanca, just as the refugees did in the famous film of the same name, to await safe passage to New York.

As the war raged on, Rother never quite settled into living in New York City. Still, she found a job as an artist and started designing geometric-patterned textiles in the style of Le Corbusier and Bauhaus, a school of European minimalism that produced architecture and objects that were practical and devoid of traditional baroque flourishes. She wrote and illustrated many children’s books that were never published and drew illustrations for Marvel Comics.

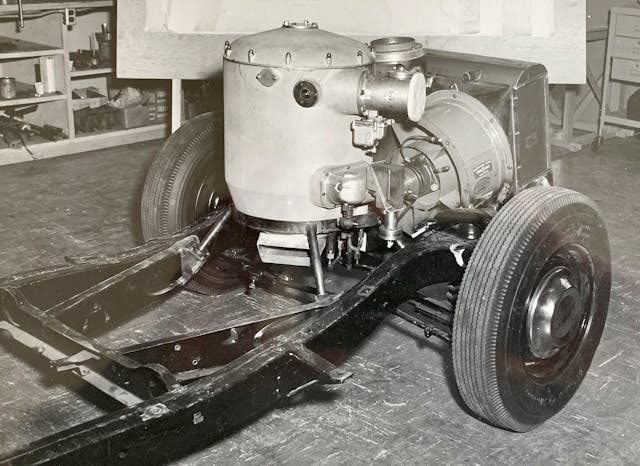

During the war, everyone did their best to get by, including car companies. With a former refrigerator salesman and car man by the name of George W. Mason running the show at Nash-Kelvinator, the company did its American duty. Instead of building powertrains for its moderately successful Ambassador Eight and Ambassador 600, it got to producing supercharged radial engines for naval aircraft. While automotive production was put on hold, in anticipation of the inevitable return to normal, Mason—a known risk-taker—never stopped new car development during those war years, including a $20 million project for a compact sedan that eventually became the Rambler.

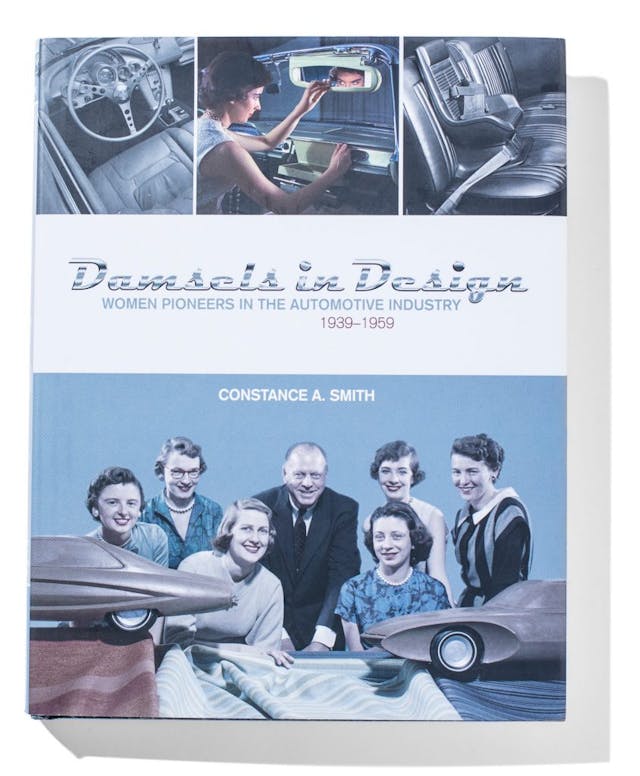

In 1942, Rother heard about an opportunity in Michigan to work for Harley Earl, the first vice president of styling at General Motors. Though the General had never hired a female designer before, much less one with radical ideas, Earl was a visionary who was seeking out like-minded creatives, regardless of their gender. According to MaryEllen Green, another of Earl’s so-called Damsels in Design—a group of female designers whom he hired after bringing Rother on board—some GM suits wanted to keep secret the hiring of any women above the secretarial level, fearing that bringing them into such a masculine industry would be a failure and an embarrassment for GM. Regardless, Rother got the job and moved to Detroit with her daughter.

“I earned less than the men I supervised,” Rother is remembered as once saying to a group of stained-glass artists. Despite her dissenters, Rother put her artistic mark on the interiors of Cadillacs, Buicks, and Pontiacs, to name a few.

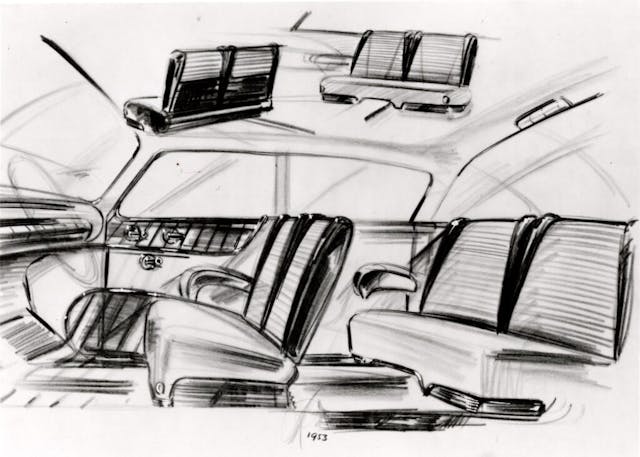

Rother turned contemporary interiors once dreary shades of black, gray, or tan into explosions of color, elegance, and convenience. “I have a long list of gadgets for use in cars beginning with outlets for heating baby bottles and canned soup, cigarette lighters on springs, umbrella holders, and so on,” Rother once wrote. Collectively, the Damsels, the pioneering women of car design, incorporated intuitive innovations, everything from improved gauge positioning to tissue dispensers. They spiced up cabins with flashy finishes and textured fabrics in the kaleidoscopic colors of an Elizabeth Arden cosmetics portfolio. As more women worked, drove, and were involved in the buying of cars, the Damsels helped GM move with the changing times.

In 1947, while still at GM, Rother started her own design studio, opening the door to her consulting for other automakers including Nash, who went on to become her main client. Rother designed seats, molding, garnish, trim pieces, and fabrics. She did extensive work on all the interiors of the revolutionary Airflyte models. The Statesman was her triumph, as she used artistic design elements incorporating color, fabrics, and texture throughout.

Statesman buyers could choose from 21 color combinations with well-considered trims and finishes. The Statesman’s interior drew particular interest for its revolutionary seating configurations. The right front seat reclined into a comfortable daybed. Fully reclined, it became a twin bed. With the addition of the driver’s seat fully reclined, the cabin became a private sleeping car. Sales skyrocketed.

***

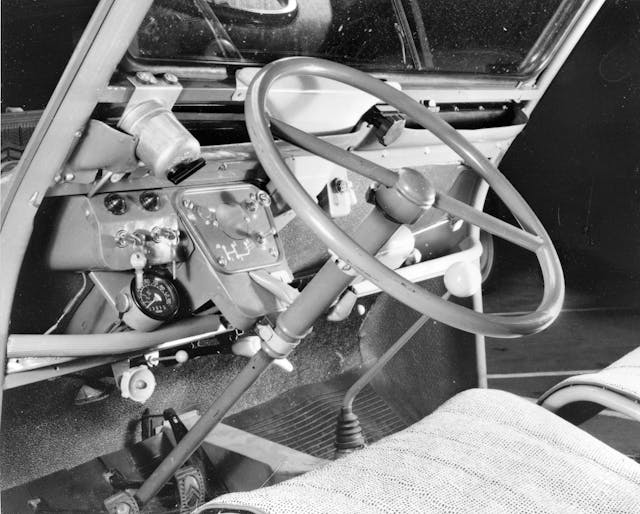

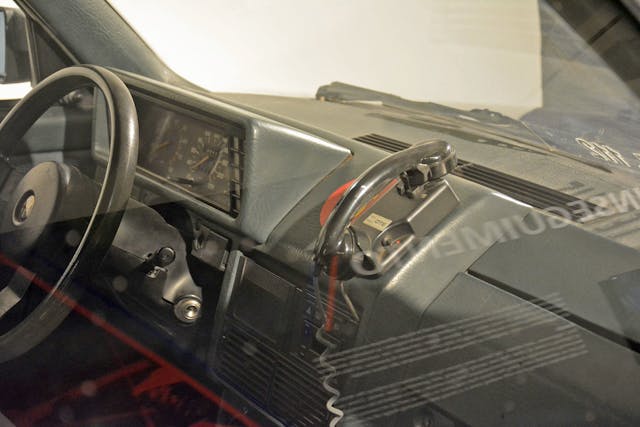

As her work gained more recognition, Rother’s prominence in the automotive industry grew. In November 1948, she became the first woman to address the Society of Automotive Engineers with a paper titled, “Are we doing a good job in our car interiors?” She inherently knew that part of the pleasure of driving a car was a driver’s interaction with the cockpit. “The instrument board of a car,” she wrote, “shows above anything else how well-styled the car is. Here the driver is in real contact with the mechanics, and here is the greatest test of good coordination between the engineer and stylist.”

Always on the hunt for what came next, Mason had been captivated by the stylish but practical designs of Italian coachbuilder Pinin Farina, as seen on the likes of Lancias, Alfa Romeos, and Maseratis, as well as the compact Cisitalia 202. This small, unfussy, yet elegant sedan likely piqued Mason’s attention, reinvigorating his $20 million wartime development idea. The time was finally right for a smaller car in the Airflyte’s lineup.

When it came time to design the body of the Rambler, there was no exterior team to speak of, as a proposed deal with Pinin Farina had not yet borne fruit. So, the company’s longtime engineers—including Nils Erik Wahlberg, who didn’t even believe in the compact car project, plus Ted Ulrich, and Meade Moore—were put to the task with only some loose design studies to work from, submitted by an independent design firm. These engineers put together a workable exterior that cribbed elements from the opulent Ambassador only in a scaled-down and more utilitarian way. At the same time, they improved mechanical issues with novel design solutions, including side air scoops to cover the connection between the fenders and the cowl. In testing, they found that the battery was 3 percent cooler than it had been previously, as it sits on the driver’s side just below the new air vent.

The Rambler, which was strongly supported by both Georges—George W. Mason and his newly hired protégé, George Romney—finally came along in 1950. As America’s postwar economy boomed, Mason and Romney saw an opportunity to put a second car in every garage. Smaller than the traditional family car but no less stylish, the Rambler was brilliantly marketed as a luxurious purchase. Certainly, there was nothing compact about its official name, the Nash Rambler Custom Convertible Landau.

Although it was smaller, the $1800 Rambler was priced several hundred dollars higher than its nearest competitors at Ford or Chevrolet. This strategy was put in place to make buyers feel as though they weren’t simply settling for a cheap, small car. Customers got a good deal for their money. In addition to Rother’s stylish interiors—which Nash promoted heavily as the work of “Madame Helene Rother of Paris” to make her sound more European—the all-new Rambler was initially only offered as a convertible and featured many standard amenities, including a radio, a heater, and whitewall tires.

The two-toned, brightly colored orange and white of the example I drove—not original—made an excellent effort of recreating what might have been an available Rother colorway. But Rother’s design was not merely stylish. The glass over the center gauge, for example, was concave, a shape that redirects light to a center focal point, which makes the driver’s information easier to see while at the same time reducing glare—rather important for a convertible. The Rambler’s interior not only looked pleasing, there was inventive purpose in every detail.

Passersby stopped to ogle the delightful Rambler as we took photos, some calling out the small charmer by name. Men and women alike beamed at what for the time would have been a diminutive pipsqueak on highways packed with rolling automotive giants. Nash’s largest car at the time the Rambler went into production, the Ambassador, is a prime example, stretching 210 inches with a 121-inch wheelbase. That’s the size of the current Cadillac Escalade. Beside modern cars, the Rambler doesn’t feel so compact as it scoots about town. It stretches longer than a modern Toyota Corolla by 3 inches, and its bulging fenders, upright greenhouse, and squared-off roofline give it the visual illusion of a more substantive car.

The Rambler’s interior asserts its Teutonic design aesthetic with clean lines and spartan ornamentation. What does exist subtly marries function and beauty. A singular, unembellished gauge using a crisp midcentury typeface displays only crucial information. (The car’s current owner added two additional gauges for vitals important to those who drive classics.) Chrome doesn’t overwhelm but rather underscores the boldly colored dash. The Rambler’s small clock sits atop a centerpiece speaker grille that could only be described as the interior’s statement jewelry. No fluffery exists, but there is art to the simplicity of it.

The bench seats are broad and comfortable, something I imagine Rother would have insisted upon. Though a small car, it can fit three abreast on the front bench and two comfortably in the rear. However, I wouldn’t want to be sandwiched between two people up front for any length of time.

The Rambler sports an inventive front suspension, one that helps explain the car’s unusual styling. The coil spring is mounted above the upper control arm to sit on top of the knuckle, attaching to the inner fender instead of a pad on the frame. This spring-above-knuckle configuration, made possible only by a high fender line, small wheels, and a casual disregard for keeping weight low, means that the springs take direct impacts from the wheel load and additionally help mitigate body roll. Also, “The lower control arms in particular are no longer subjected to vertical bending loads and hence can be made lighter, with less unsprung weight,” said Meade Moore, chief engineer at Nash at the time of the Rambler’s launch. Because this configuration stands quite tall, it limited exterior styling and design choices, helping give the Rambler a face rather like a chipmunk with its cheeks full of acorns.

Mason and Romney wisely leaned into the lifestyle of their targeted customers (mainly women) for the Rambler. One wonders if this were influenced by Rother and her belief that style meant a great deal to buyers and that women of the time liked gadgets. Images of women driving the car using its additional standard features, including the glove drawer, filled the pages of glossy magazines of the era. Marketing brochures featured the varied interior colors and textiles customers could purchase with the tagline, “There’s much of tomorrow in all Nash does today.” Ads assured potential buyers that despite its convertible top, it was just as safe as a sedan.

Initial sales of this petite econo-luxe oddball were impressive, spawning iterations of the nameplate in the form of a wagon and a hardtop. In 1950, its first production year, Nash sold over 11,000 cars. That climbed to 57,000 for 1951 with the addition of the hardtop. Although the gross national product had ballooned from about $200 billion in 1940 to $300 billion by 1950, it was accompanied by rampant inflation, housing shortages, and a scarcity of raw materials caused in part by the Korean War (one reason the Rambler was launched as a convertible was that it used less steel than a hardtop).

Rother’s growing frustration at the wholesale dismissal of women as both automotive designers and customers became apparent during a speaking engagement in Detroit in May 1952 commemorating “Get the Dents out of Your Fenders” month, which was a nationwide campaign to promote car repair in the face of dwindling new-car inventory. Barbara Tuger, a reporter with the Detroit Free Press, quoted Rother as lamenting, “Once a car is sold, little is said about how (the female buyer) should care for it.” In fact, she declared, “Less is done in this country to attract the woman buyer than in Europe.” But even Tuger seemed to belittle and even mock Rother’s accent with her article’s headline, “Oo, la, la, Zose Dents by Women Drivers.”

Rother went on to describe new cars being presented as fashion in France. “They are used as a background for a style-conscious life, and more than half the visitors at an automobile exhibition are women. Here, it is mostly the teenaged boys who come,” Rother said.

As sales started to decline in 1953, the Rambler got the long-awaited Pinin Farina magic touch. The chubby hood and fenders were stretched and slimmed by the Italians, becoming more graceful and elegant in the European mien. But neither the new looks, the launch of a less expensive two-door sedan version, nor using both Rother and Pinin Farina in advertising campaigns could help the decline in sales. Nash merged with Hudson in 1954 to form American Motors, providing Nash with a massive dealer network. Nevertheless, not even that nor the subcompact Metropolitan, now highly collectible, could save the company from its inevitable downward slide.

After leaving Nash, Rother went on to work with clients including Goodyear Tire, BFGoodrich, Magnavox, and International Harvester. Some of her stained glass still graces cathedrals around Detroit. Later in life, she dedicated herself to her own work and her horses, but her legacy quietly continued, even if it was temporarily unrecognized.

The automotive community has not showered either that first Rambler or Rother with accolades or credit where it was due. But all you have to do is look to American interior styling of the 1960s and ’70s in the Chevrolet Corvette, the Lincoln Continental, or the Pontiac Trans Am, with their flashy colorways and innovative features and design, to see the influences. The modern compact Cadillac CT4 and electric Chevrolet Bolt come with luxuries and conveniences that include smartphone connectivity and heated leather gravity seats—modern gadgets like those Rother knew drivers craved. Some full-size trucks even have optional center-console coolers. On some levels, all these vehicles can look back to the Nash Rambler and Rother’s interiors and find their DNA.

As more women entered the contemporary automotive arena, Rother’s name, among others, was resurrected. In February 2020, a well-overdue 21 years after her death at the age of 91, Rother’s significant contribution was duly acknowledged, and she was inducted posthumously into the Automotive Hall of Fame (in the same class as our own Jay Leno). No doubt it was thanks in part to the stylish collision of a freethinking designer and an innovative automaker, both a bit ahead of their time.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

The post The Free-Thinking Genius of Helene Rother and Nash Motors appeared first on Hagerty Media.

]]>

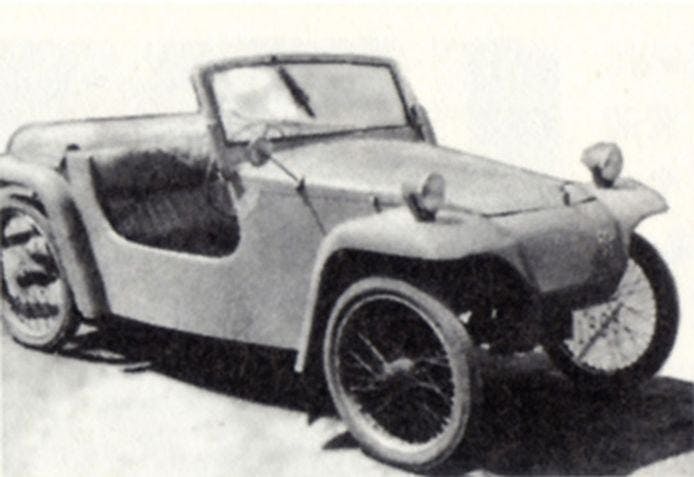

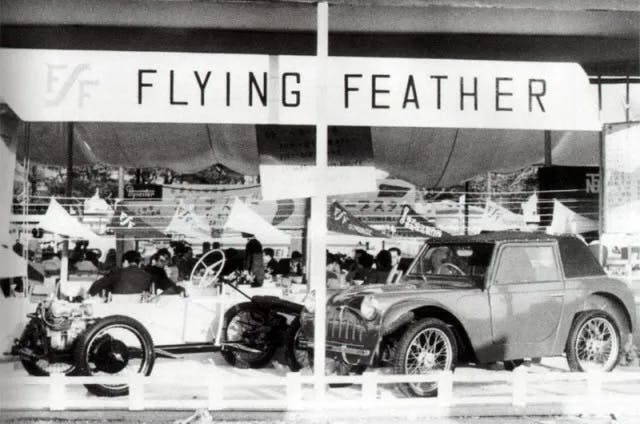

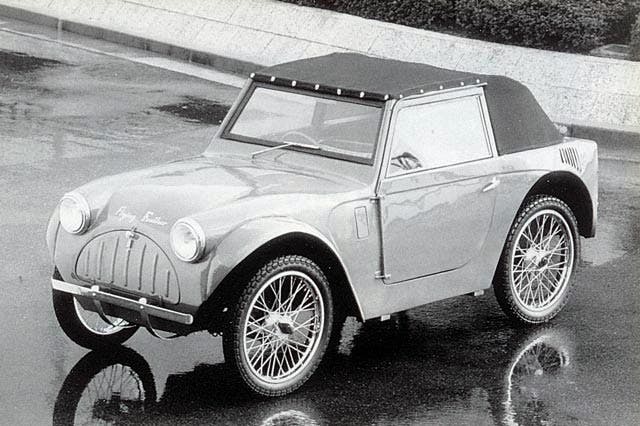

Call it a cyclecar or a microcar, the Suminoe Engineering Works Flying Feather was the right car at the right time for war-ravaged Japan of the 1940s. The driving force behind the car was Yutaka Katayama, now known as the father of the Datsun 240Z and the man who brought Nissan to the United States. However, his imaginative design met with a quick demise after only 200 examples were ever produced. The Flying Feather has become a forgotten car that should be held to much loftier status.

“Mr. K” was a Nissan man. Since 1935, he had worked for the auto manufacturer doing advertising and promotional work. After Nissan restarted production following WWII with its prewar Austin 7 DA and DB variants, plans were afoot to dive deeper into the Austin portfolio to bring more up-market sedans to Japan. Nissan was eyeing Austin’s A40 and A50, both larger cars than the ancient Austin 7.

But in 1947, Japan was struggling with ramping up production of even the most basic products. Raw materials, supply chain issues, a collapsed economy, and generally dismal working and living conditions didn’t translate to eager buyers of large English sedans. Katayama knew this, and felt that a bare-bones economy car was the way to kick off not only the rebirth of Nissan but also that of Japan. It was the same rationale that produced Germany’s Beetle and France’s 2CV. Both vehicles would begin production in 1947, the same year in which Katayama began envisioning their Japanese counterpart.

Nissan designer Ryuichi Tomiya was of a like mind with Katayama. Well-known throughout Japan for his various automotive and industrial designs, the future director of the Tomiya Research Institute would go on to design several important cars including the Fuji Cabin three-wheeler. Back in the 1940s, he was not up for rehashing Austins even though Nissan was dead set on going upmarket with the larger Austin A40 sedan.