Porsche’s First Four-Door Was a Studebaker

It’s fairly well known among aficionados of automotive trivia that Studebaker was the official American distributor for Mercedes-Benz cars in the 1950s. Less well known is the fact that the independent automaker based in South Bend, Indiana, had an earlier relationship with another German automaker, Porsche. Ironically, at the same time that the automotive operations of the Studebaker Corporation were deteriorating financially, Studebaker’s tie-up with Porsche helped it get established as a serious automaker.

Long before the Panamera, Cayenne, or Macan changed Porsche’s image from that of a maker of high-performance two-door sports cars to a manufacturer of luxury executive and family cars, Porsche developed a four-door sedan for Studebaker.

The history of the Porsche company dates to the engineering consultancy founded by Prof. Dr. Ing. h.c. Ferdinand Porsche in 1931 with his son-in-law Anton Piëch and Adolf Rosenberger, a businessman and gentleman racer who had succeeded both as a privateer and as a factory driver for Mercedes-Benz. While the engineering firm was started by Dr. Porsche, the first Porsche cars were developed by his son Ferry in 1947 while the elder Porsche was still in prison for his contribution to the Nazi war effort and the use of slave labor in his Stuttgart facility.

Ferdinand Porsche died at the age of 75 in early 1951, soon after his family secured his release from prison by paying French authorities a fine that was essentially a ransom. Late that year Ferry Porsche came to the United States to meet with Porsche’s North American importer and distributor, Max Hoffman. He asked Ferry if he was interested in doing contract engineering for American firms. Porsche jumped at the opportunity to provide additional revenue for his fledgling company, so Hoffman put Ferry in touch with a friend, Richard Hutchinson, Studebaker’s vice president for exports.

By the early 1950s, Detroit’s Big Three automakers were using their great resources and economies of scale to put serious pressure on independents like Studebaker. Hoffman, who by then was also importing and distributing Volkswagens, suggested that Studebaker should sell something small and inexpensive, like the Beetle, as no American car company was then serving that market. Hutchinson didn’t need much convincing; he had earlier negotiated with the British occupation authorities, who had started the postwar VW company out of the ruins of the Wolfsburg KdF plant, to ship him one of the first Beetles in the United States.

(Impressed by the Type I, Hutchinson had actually negotiated a contract to be the American distributor for VW, but Harold Vance, the president of Studebaker, killed the project.)

Still, Hoffman and Hutchinson arranged for a team from Porsche to meet with Studebaker executives in the spring of 1952. Ferry Porsche was accompanied to South Bend by designers Karl Rabe and Erwin Komenda as well as chassis engineer Leopold Schmid.

They brought with them a standard 356 coupe out of Hoffman’s inventory and an experimental four-seater designated Type 530, essentially a 356 that was stretched enough to make room for a rear seat, with longer doors for rear seat access and a slightly raised roofline for headroom in back.

According to Hoffman, the initial testing of the 530 at Studebaker’s proving grounds did not go well. With Ferry Porsche in the passenger seat and Vance and Hutchinson in the back, Hoffman steered the prototype around the track. He was not impressed. “It was a terrible car,” he told automotive historian Karl Ludvigsen. Still, the Studebaker execs were impressed enough to continue the meetings, with the company’s VP of engineering, Stanwood Sparrow, and chief engineer, Harold Churchill, joining in.

Instead of having Porsche develop an American people’s car (something Henry Ford had originally accomplished with the Model T), Studebaker ended up contracting with Porsche to develop a conventional front-engine car similar to the existing ’52 Studebaker Champion sedan, only with more power and less weight. It was also designed to take advantage of modern manufacturing methods.

Despite Hutchinson and Hoffman’s enthusiasm for the idea, it’s not surprising that the Studebaker managers in general were not very interested in a small, air-cooled, rear-engine American people’s car. None other than Henry Ford II turned down the opportunity to acquire the entire Volkswagen company, when presented with that offer gratis by the British in 1948.

The design brief that Studebaker gave Porsche specified a six-cylinder, air-cooled engine, a three-speed transmission, and a maximum achievable speed of 85 mph.

Ferdinand Porsche had Austrian ethnicity and was Czech by birth, not German. Ferry Porsche built the first production Porsche cars in a sawmill in Gmünd, Austria. Later, Reutter Karosserie in Zuffenhausen, near Stuttgart, Germany where the Porsche engineering firm was located, took over body assembly. When Ferry Porsche and his crew returned to Zuffenhausen from America, they were still working in wooden sheds. The Porsche company built its first proper assembly plant across the road from Reutter in 1952. The money from Studebaker made the move to that factory possible.

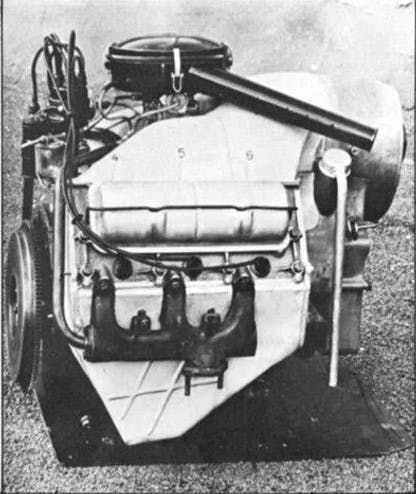

The six-cylinder engine that Porsche came up with was rather novel. It was a V-6 design, a configuration which was not very common in the early 1950s. The only V-6 in production at the time was a relatively small 2.0-liter engine by Lancia. Larger displacement V-6 engines aren’t smooth because of inherently unbalanced secondary rotational couples. Today that problem is addressed by counter-rotating balancing shafts.

To address primary balancing issues, most V-6 engines are 60-degree designs. (The GM 3800 was a 90-degree design made by hacking off two cylinders from a V-8, but it ran like a 60-degree six due to trick, offset crankshaft journals.) Instead, Porsche went with a 120-degree design because the crankshaft would have only three throws, with two connecting rods on each journal, compared to the six journals needed for a 60-degree motor. It was cheaper and simpler to manufacture and the relatively compact and lightweight crankshaft meant the unbalanced forces were reduced. According to Karl Ludvigsen, it may have been the first 120-degree V-6 ever made.

The engine was further novel in that it had hybrid cooling. The cylinder heads were air-cooled, while the cylinders were water-cooled with a small radiator placed inside the ductwork for the head. The use of liquid cooling for the cylinders also provided a reliable source of heat for the passenger cabin.

Ferry Porsche and Karl Rabe returned to South Bend in the early fall of 1952, with drawings and 1:5 scale models. Studebaker approved the overall design but apparently had misgivings about the hybrid cooled engine. Studebaker commissioned Porsche to also develop fully air- and liquid-cooled versions of the V-6.

Another contract was drawn up for Porsche to build a prototype and several extra engines for testing, and Porsche gave the project the internal designation of Type 542.

In early 1953, Porsche moved into its new factory, where development of the 542 proceeded, with fabrication of the body and engines taking place in the fall of that year.

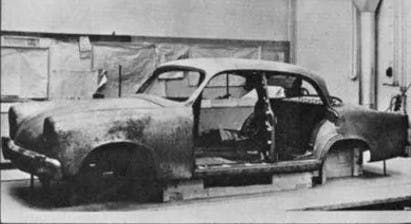

The result was a four-door sedan, with pontoon fenders, that was slightly wider and a bit shorter in length (111-inch wheelbase vs. 115) than the 1952 Champion. The design brief from South Bend specified the use of many production Studebaker parts including wheels, drum brakes, the Commander model’s transmission (a three-speed manual with overdrive), door handles, steering wheel, and a Saginaw steering box.

Those specifications were relatively easy to accommodate but another Studebaker requirement posed a greater challenge. Porsche was developing a unibody architecture but Studebaker’s assembly plants in Indiana and California were set up to build body-on-frame (BOF) vehicles. BOF car bodies typically end at the firewall, with a separate front “clip” mounted separately to the frame. A body made with unibody construction is necessarily longer than the main part of a BOF body. To accommodate such a body, not only would the assembly plants need to be reconfigured, but Studebaker would have issues shipping the bodies by rail to California. To save space, bodies were placed vertically on special railcars, but the longer unibodies would not fit in the mountain tunnels on the way to the Golden State.

The finished 542’s “unibody” was actually made in two parts, with a separate front end with its own boxed structures, essentially two unibodies bolted together. Two different front structures were designed to accommodate a radiator for the water-cooled version, and air ducts for the air-cooled edition. Reutter was responsible for fabricating the 542’s body.

Like other Studebakers, the front suspension used coil springs and tube shocks but instead of conventional A-arms as used in American cars, the 542 used dual trailing arms like you would find on a VW Beetle. Unlike other Studebakers, the 542 had independent rear suspension, not for better performance, but because fixing the differential in place allowed for a lower driveshaft and a flatter interior floor. The semi-diagonal trailing arm rear suspension presaged its use years later by Porsche and BMW.

Regarding the engines, Ferry Porsche would have rather used aluminum but Studebaker was used to casting and machining iron and steel, so the air-cooled version—designated 542L, for luft, German for air—had both iron heads and individually finned, cast-iron cylinders. The heads and cylinders were fastened to the crankcase with long bolts, a setup familiar to anyone who has rebuilt an air-cooled VW or Porsche engine. Porsche made the crankcases for both engines as short as possible, to save some weight with the ferrous parts.

Both the 542L and the 542W (W for wasser, water) were overhead valve designs with wedge combustion chambers, and had the same oversquare dimensions with 3054cc (186-cubic-inch) displacements. Both motors used aluminum pistons.

It’s clear that Porsche was using the 542 project to expand and develop its own technical abilities. While the 542W got a conventional forged steel crankshaft, the 542L had a cast one made from nodular spheroidal-graphite iron—again, a technology that would be embraced by the industry later.

Ignition systems from both Autolite and Delco-Remy were tried. Fuel was supplied by a single Stromberg carburetor through a six-armed intake manifold that stretched across the wide 120-degree vee, although at least one prototype engine had dual carbs.

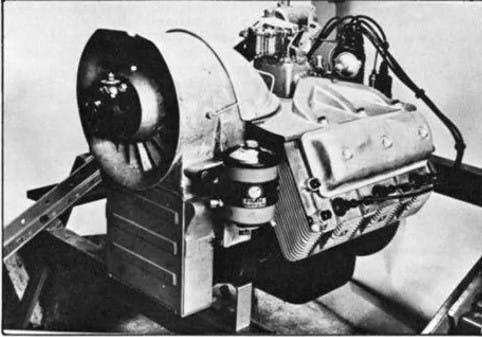

The 542L used an axial-flow fan, instead of the squirrel-cage fans on air-cooled VWs and Porsches. Concentric with the cooling fan and driven by the same belt was the engine’s generator and an oil cooler, a critical component for air-cooled engines, was integrated into the air flow. To keep things compact, all the ancillaries of the 542W were mounted inside the vee. Because of the need to drive the cooling fan, the 542L had slightly less power: 98 bhp (96.7 hp) at 3700 rpm, compared to the 542W’s 106 (104.5) @ 3500 rpm.

In early 1953, Raymond Loewy, Studebaker’s outside design consultant, and Robert Bourke, who was working in South Bend for the Loewy studio, traveled to Stuttgart to see how things were going with the body. Since the finished prototype doesn’t look out of place with Studebaker’s lineup at the time, it’s clear that Loewy and Bourke had some input. While styling was not actually part of Porsche’s commission, the finished product also shows some Porsche DNA. It was nothing revolutionary, after all Studebaker was a rather staid company, but the result can well be described as handsome.

Studebaker management got its first look at the finished 542 in March, 1954 on the occasion of the Geneva auto show. While the 542 was not displayed at the show, Harold Churchill, by then VP of engineering in South Bend, and Klaus von Rucker, a German-born engineer who was second in command at Studebaker’s R&D department, were at the show. Ferry Porsche drove them back to Stuttgart in the 542.

After further shakedown tests in the Swiss mountains, the 542, with dark metallic blue paint and saddle brown upholstery, was shipped to Indiana along with the extra engines in the autumn of 1954. In an article for Special Interest Autos, Karl Ludvigsen says that the car was tested with both engines. Since only a single prototype is mentioned, presumably the engine swap was done in South Bend, likely facilitated by the bolt-on front ends. Likewise, both engines were fully dynamometer-tested.

Though the 542 missed the target weight by over 500 pounds, Studebaker personnel were still impressed with the prototype. Harold Churchill considered the Type 542 to have been “an excellent job.” Ed Reynolds, who was on the staff of Studebaker’s proving grounds, called the 542 “a solid little thing.”

Why, then, did the Type 542 never see production? The simplest explanation is a lack of money. “By the time it arrived, the interest in it had departed,” Reynolds said. That departing interest was likely due to Studebaker’s pressing financial concerns. Less than a month after the 542 arrived for testing, Studebaker’s financially struggling automotive operations were merged with Packard to form the ill-fated Studebaker-Packard Corporation.

What about the 542L and 542W engines? Studebaker could have used a modern six-cylinder engine, and didn’t introduce its own overhead valve inline six until 1961. Like the 542 project as a whole, a lack of finances probably killed the Porsche-designed bent six. Churchill said, “The problem was the capital to tool it.” To put the engine into production would likely have cost $15 million to $20 million in 1954.

To get an idea of how precarious Studebaker’s finances were, that figure works out to about $200 million in 2024 dollars. That seems like a lot of money but it is a fraction of the cost of putting a brand-new engine into production these days, which is close to a billion dollars or so.

Studebaker did have a respite from following at least some of Max Hoffman’s original advice. In 1959, the company introduced its first compact car, the Lark. The Lark sold over a quarter million units in its first two years, reviving the company, at least until the Big Three automakers introduced their own compact cars. Lark sales halved in 1962 and Studebaker ended production at South Bend just before Christmas in 1963. Studebaker car production would end for good when its plant in Hamilton, Ontario, shut down in 1966, though a few knock-down kits may have been assembled after that by Studebaker’s importer in Israel.

The prototype 542 no longer exists except in photographs. At least one 542L engine still exists in Porsche’s corporate collection and has been on display in the company’s museum in Stuttgart.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Great Story. Porsche engineering has contributed to a number of vehicles quietly.

The one many never knew about was the 1988 Fiero suspension. Lotus got the credit but the truth was Porsche Engineering Tuned it.

Pontiac wanted to get a new suspension for the car from even before it went into production. It was 1988 before they had the money.

In 1984-85 Pontiac had the suspension they designed but they hired Porsche to tune the turn in and on center feel.

Remember this was at a time Chevy was going head to head with Porsche with the Corvette in Showroom stock racing. Also Pontiac had two 2.9 Turbo prototypes they called the Porsche Eaters. Their tail lights would light up and state this at night. The tail lamps were removed and Chevy was not told of Porsches help.

Keep in mind Porsche has purchased a Corvette at this time and tore it down looking for where they were getting beat. In the End the Corvette was banned and the Z/28 came in and continued to win.

GM at this time had a number of SCCA road racers that were also their engineers on suspensions so they really put a lot of effort into this and the engines. GM would run out of money by the time they got to the interior.

Tom Goad Pontiac racer and engineer was very sensitive to the fact that he and his team made the 1988 Suspension. He declare it was GM but Porche did help in the tune do to their work with rear engine cars.

GM also has used Lotus as recent as the LNF turbo 2.0. They did a lot of work for the oil and heads as did SAAB engineering.

Mercury Marine enlisted Porsche to help develop an outboard motor. In 2005 Mercury introduced the Verado, a 2.6 liter supercharged, intercooled inline 6. Power ranged from 200 HP to 275 HP depending on model. It was considered by many to be overweight and needlessly complex.

I always enjoy your well informed comments and your fair, even-handed approach to the sometimes passionate world of classic cars. I don’t consider a Hagerty article as read until I have read your comments. Just one point: how about writing them out first in a word processor that checks for spelling and grammar, and then copy/paste them? There are enough clangers, typos, and mistakes that the reading experience can be a bit rocky…

Great article! l don’t recall the subject of the Porsche/Stude prototypes having been better covered!

Studebaker evolved their own engines as resources and circumstances dictated (like not getting use of an AMC six, as they had hoped). l’m not sure that the hybrid cooling system would not have been any better accepted than, say, the “rope” driveshaft on Pontiac Tempests. It would have perhaps just been another excuse for those folks who are fans of other brands to think of Studebaker as “oddball”.

The premise of the title of the article is a really interesting observation! However the last sentence of the first paragraph is a little ambiguous. l pretty sure it was intended to read something like “….Studebaker’s tie-up with the fledgling Porsche concern helped establish the German company as a serious auto maker”. The original wording sort of sounded like Studebaker was not previously a serious auto maker – and nothing could be further from the truth.

RE: Porsche’s First Four-Door Was a Studebaker

This four-door sedan resembles the 1955 Willys four-door sedan?

The VW Bettle was imported into the USA beginning in 1949?

A few factual corrections to this article…

“while the elder Porsche was still in prison for his contribution to the Nazi war effort and the use of slave labor in his Stuttgart facility.” – Ferdinand Porsche was acquitted of this accusation and found innocent of the charges by three separate tribunals – first the American, then the British, and finally the French (after his imprisonment and release).

“Ferdinand Porsche had Austrian ethnicity and was Czech by birth, not German.” – with the ever-changing country boundaries that occurred within Europe during the 19th and 20th centuries, a person’s ‘ethnicity’ and identity were NOT defined by their country of residence nor citizenship. The majority of Austrians are of German ethnicity. There were large swaths of ethnic Germans living in Hungary, Rumania, Czechoslovakia, Poland, even Russia (Volga region) as well as other countries. Ferdinand Porsche was German – period!

Indeed. Born in 1875 in the Austro-Hungarian empire, Ferdinand Porsche was not “Czech” or even “Austrian” in any way at all — he was an ethnic German born in Bohemia (which would later form part of Czechoslovakia, and is a constituent part of the Czech Republic).

Porsche also developed the V2 engine for the Harley Davidson V-Rod in 2002. I wonder if Porsche got the idea for the 924 with the transaxle and independent in the rear from the 1964 Tempest with 50/50 weight distribution.

Not likely. The transaxle layout, in more or less the current form, was used by Lancia in 1950 and Pegaso in 1951 and probably by others before that. The Tempest used swing axles (see early Corvair) while the 924, 944, and 968 transaxle Porsches used semi trailing arms in the rear. While both are independent suspensions there is a huge difference in the way they handle. Having spun a 1963 326 V8 Tempest Convertible 180 degrees on the old S curve on Lake Shore Drive in Chicago in 1971 and having driven a 944 Turbo on the autobahn at 160+ in 1986, I can tell you there is a world of difference between the two as far as handling between the swing axle and a semi trailing arm set up. Porsche more or less got the semi trailing arm suspension layout on the 924 and 944 from later model VW’s. (at least the original steel versions). VW quit using swing axles after 1968. Too bad Pontiac never got the chance to adapt the 1965+ Corvair rear suspension on a production transaxle Tempest.

1960-1963

I did not know of Porsche and Studebaker working together on a car or engine before. Pretty cool to see even if the car never saw production.

Count Albrecht von Goertz’s styling studies for what would become the BMW 507 were done at Studebaker.

Fascinating story. Could Studebaker have sold that car at a profit? Somehow I think that it would have been expensive… and Americans buy cars by the pound.

Fascinating article, wonderful historical value, kudos to the author.

This car is in the Studebaker National Museum in South Bend Indiana

The car at the Studebaker National Museum is a standard 1959 Lark with a production Porsche air cooled 4 fitted in the ‘trunk’. It is not the Porsche built 542 bodied prototype featured in the article.

Memories of the Lark. It was the pursuit vehicle of choice for the police force in my neck of the woods during the mid-sixties.

The picture you show of a “1952” Studebaker Champion is a 1953 Model designed by Raymond Lowe

Studebaker had a transaxle on a 1917 Studebaker seven passenger touring car my dad had one !

Very informative history. Two thumbs up even with corrections!