Sadly, Ducati’s Supermono Single Was Never Built to Mingle

Ducati has just unveiled a new single-cylinder roadster, the Hypermotard 698 Mono. The new bike inspires nostalgia for the sporty single that, more than 30 years after its introduction, remains one of the firm’s best-loved, rarest, and most valuable models: the Supermono race bike of the 1990s.

Like a rock star who died young, the Supermono had everything required to become a legend. It was a beautiful, brilliant creature that shone briefly before being extinguished, leaving its fans wanting more—in this case, a road-going version that was promised but never produced.

On its debut in 1993, the Supermono was instantly successful. Ducati’s works rider Mauro Lucchiari rode one to win the European Supermono championship in its debut season. Its numerous race wins over the next few years included a 1995 Isle of Man Singles TT victory by New Zealander Robert Holden.

And the Supermono was more than just a winner. It was small, ingeniously engineered, and exotic—a lightweight construction of magnesium, aluminum, and carbon fiber. And it was delightfully styled, by South African designer Pierre Terblanche, who would go on to shape many V-twins for the Bologna firm.

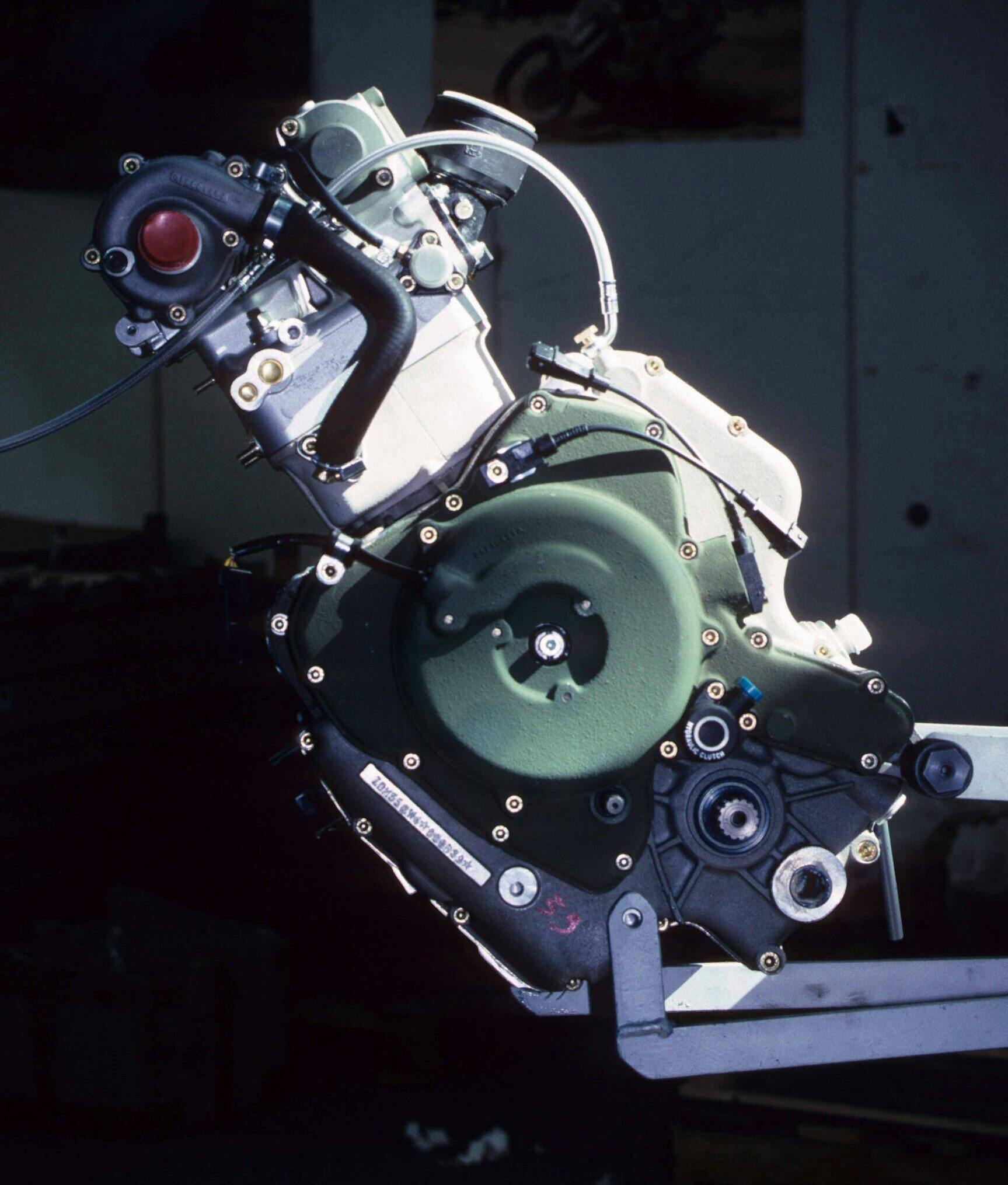

Few bikes have had more illustrious parentage. Its 549cc, liquid-cooled engine was designed by Ducati’s chief engineer Massimo Bordi, who had created the eight-valve, DOHC desmodromic V-twin that had revitalized the firm’s image. The single was essentially the V-twin with its vertical cylinder replaced by a vibration-canceling dummy connecting rod.

And the Supermono development team was led by a young engineer named Claudio Domenicali, who had joined Ducati in 1991, not long out of Università di Bologna. He would rise swiftly through the ranks at Ducati, eventually becoming CEO in 2013, and has since led the firm to unprecedented success.

My chance to ride the Supermono came in June 1993, after I had managed to bypass Ducati’s press department in order to speak to Bordi, who said I could use the factory’s test track. On arrival I met Domenicali, who had been tasked with putting Bordi’s dummy conrod theory into practice.

This had not been straightforward, as he explained. “Engineer Bordi had the idea and gave it to us to develop, but there was a phase when we were not sure it was good. Then we made a computer program that calculated all the forces generated by the movement of the system, and we realized what the problems were.”

The engineers had initially assumed that the dummy conrod and balance-rod should weigh the same as the piston assembly, but that had proved false and the final set-up was lighter. “We spent lots of time on this; not just on the weight but on its distribution too,” Domenicali said.

The effort had been worthwhile, however. The engine produced its peak output of 75 bhp (74 hp) at 10,000 rpm—much higher than most singles—and could safely be revved to 11,000 rpm. Its smoothness meant the frame and other components could be lighter for further increased performance.

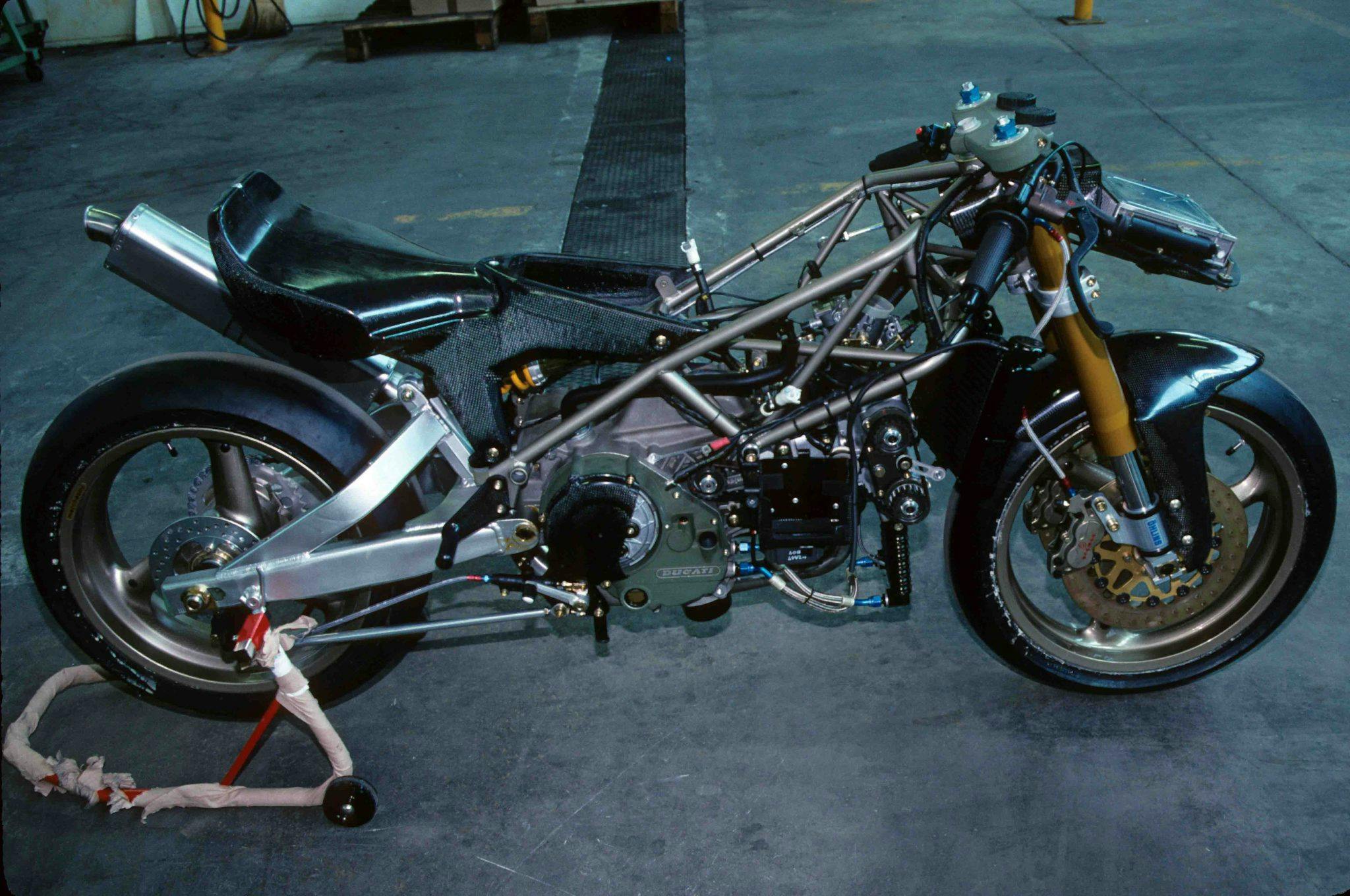

At the time of my visit, the second batch of 15 hand-assembled Supermonos sat in line, awaiting their carbon-fiber bodywork before being ready for shipment. Alongside, on stands, were partially built engines, each with a distinctive crankcase hump hiding the dummy conrod arrangement.

Whether stripped or fully dressed, the Supermono was an exquisite motorcycle. Its low screen sat above the carbon fibre fairing’s nose duct, which split before feeding the Weber-Marelli injection system. The tailpiece supported its own weight with another stylish sweep of carbon.

Exotic materials were everywhere. The striking, flat-topped fuel tank was made from a blend of Kevlar and carbon fiber. And the purposeful look was backed up by classy details: magnesium triple-clamps and engine cases; and carbon-fiber brackets holding instruments, the battery-box, the footrests, and the silencer.

The frame, a minimalist blend of 22mm and 16mm steel tubes, weighed only 6 kg (13 pounds) and used the motor as a stressed member, in traditional Ducati fashion. Its stiffness-to-weight ratio was the factory’s highest yet, Domenicali said. The swing-arm was a sturdy aluminum structure.

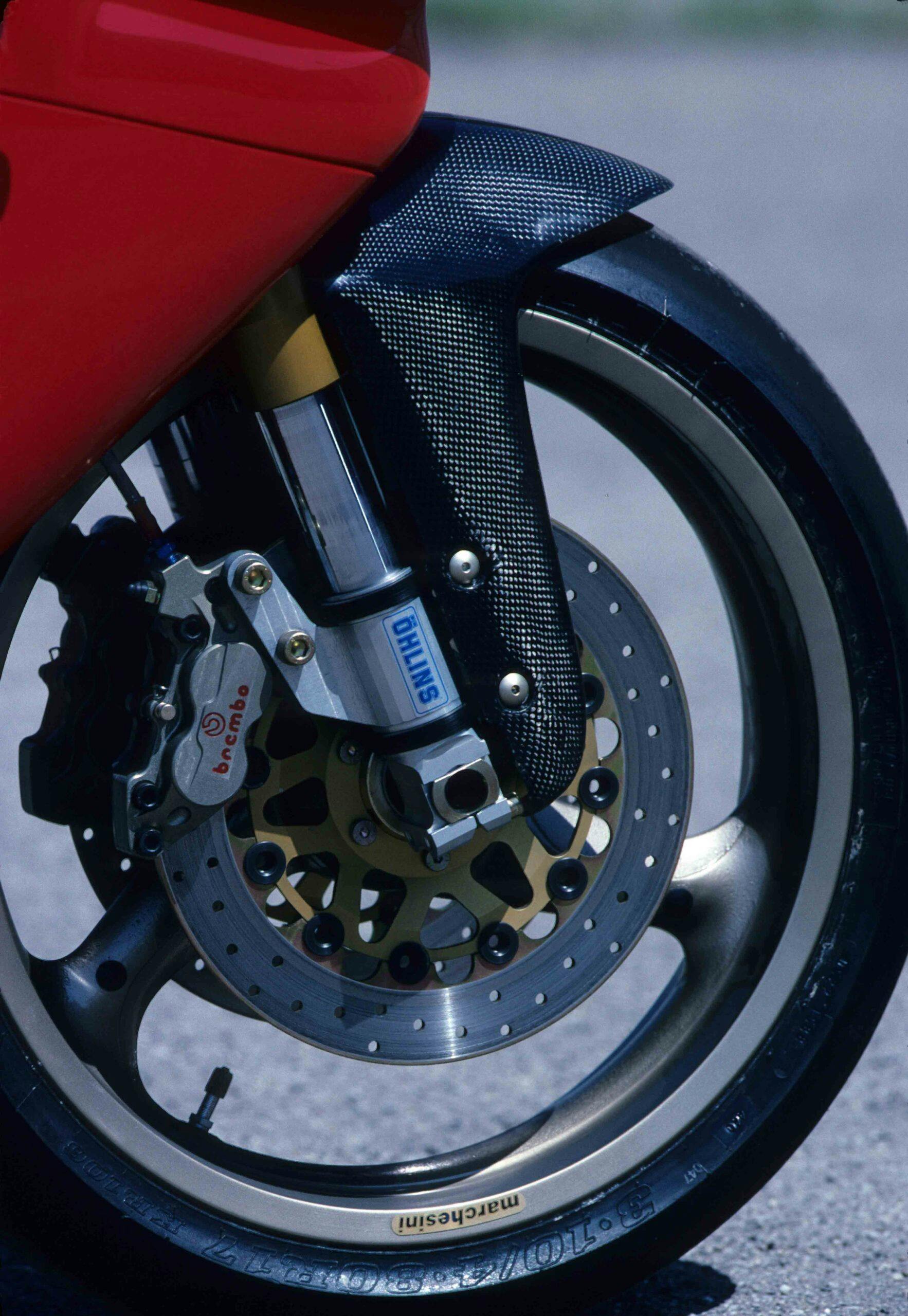

Sophisticated, race-quality suspension came from Öhlins, comprising upside-down forks and a rear shock unit worked directly by the swing-arm. The 280 mm (11-inch) Brembo front brake discs seemed huge for a bike so small. Another Italian specialist, Marchesini, supplied the lightweight magnesium wheels.

Lucchiari’s championship-leading bike was the only Supermono reserved for the factory’s own use, so that was what I’d be riding. Domenicali started its engine using rollers, in racing fashion, and blipped the throttle until it was thoroughly warmed. After pulling away I was equally careful to warm the Michelin slick tires.

The “factory test track” sounded glamorous but was in reality a narrow, little-used ribbon of asphalt that wound round the Borgo Panigale plant, occasionally passing doors where I had to trust that the workers inside knew what was happening and wouldn’t suddenly emerge pushing a pallet of parts.

Thankfully that didn’t happen, and the supremely light and agile Supermono was ideally suited to the track. Its claimed dry weight was just 118 kg (260 pounds), and this was mostly held low, due partly to the engine’s horizontal surviving cylinder. The bike responded instantly to the slightest pressure on its low handlebars.

And it was quick—far quicker than any single I’d previously ridden. The track essentially comprised just two short straights, separated by a curve, with tight loops at either end. But there was enough space for the Supermono to demonstrate its acceleration as I wound open the throttle exiting the slow turns and trod down through the race-style down-for-up gearbox.

As the revs rose to send the little red bike charging forward, its exhaust note hardened from a gentle chuffing to an angry road-drill snarl. When I shut off at the end of the straight, with the white-faced tachometer nudging 10,500 rpm, the lack of vibration—just a slight tingle through bars, pegs, and the thinly padded seat—ensured that it felt like no other single-cylinder motorcycle.

Inevitably, the highly tuned little motor couldn’t match a bigger V-twin’s midrange performance, so it relied on its close-ratio gearbox to cover for a lack of urgency below 6000 rpm. But it wheelied easily on the throttle in first gear, and kicked hard through the seat in its lower three ratios. Given more space, it would have been good for over 140 mph.

I’m tall, and I struggled to get comfortable on a bike whose racy, feet-high riding position was designed for a much smaller pilot. That didn’t prevent it from feeling delightfully precise and controllable as I began to enter turns harder, relying on the taut suspension and warm, sticky slicks.

The Supermono cornered and stopped as well as just about anything on two wheels, and its racing lap times proved it had the performance to embarrass plenty of much bigger bikes. The prospect of a road-going replica was mouth-watering—and, in 1993, very much part of Ducati’s plan. Bordi’s engine design incorporated a boss for a starter motor in the crankcase.

Back in the race department, after my dozen-or-so laps, Domenicali confirmed that Strada, or Street, derivatives were on the way. “There will be two versions,” he said. “One will be a super-sports, with water cooling and fuel-injection, like a replica of the race bike. The other will have a lower price and different road styling, with an air-cooled motor and carburetor.” After a pause, he added: “We have all we need to complete the project, but we have so many projects under development that we don’t know when these ones will be started.”

Ultimately, those other projects would halt the Supermono street bike project in its tracks. Firstly, the recently launched M900 Monster became an unexpected hit, starting a naked V-twin dynasty. Months later, the firm unveiled the 916 that took superbike desirability to unprecedented heights.

With demand for the V-twins soaring, and Ducati’s financial problems already causing delays in production, the factory simply never reached the point at which it could commit to a road-going single.

Bordi and Domenicali had hoped to have both Supermono streetbikes on sale in 1995. In reality, only the race bike was produced, and in tiny numbers: just 40 units of the original 549cc bike in 1993, followed by a further 27, with larger capacity of 572cc, in 1995.

A few road-going Supermonos were built, a decade or so later by British engineer and Ducati expert Alistair Wager, who had worked as a mechanic on 20 of the 67 race bikes. Wager bought a batch of Supermono parts from Ducati, commissioned many more from a range of suppliers, and assembled a small run of superb street-legal singles that incorporated a few improvements of his own. All were quickly sold.

These days the genuine Supermono racer’s rarity merely adds to its allure, and of course to its value. When, every so often, a clean and original example reaches auction, the serious bidding starts north of $100,000.

Soon, though, the new Hypermotard 698 Mono will offer a more realistic alternative. Its 659cc “Superquadro Mono” engine makes 77 bhp (76 hp), features desmodromic valvegear, and is smoothed by twin balancer shafts instead of a Supermono-style dummy conrod.

More than three decades after the Supermono conquered all on the track, Claudio Domenicali is finally set to put a single-cylinder Ducati on the street.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Sounds like an interesting experience. I expected there would be a lack of torque but was still a bit surprised to hear how smooth the power was.