The Audacious PR Stunt to Prove That the Chrysler LeBaron Was a World Beater

This article first appeared in Hagerty Drivers Club magazine. Click here to subscribe and join the club.

The early 1980s were a turbulent time for the U.S. economy. Inflation, high interest rates, and rising concerns about things like imported goods and a shifting job market. Sound familiar?

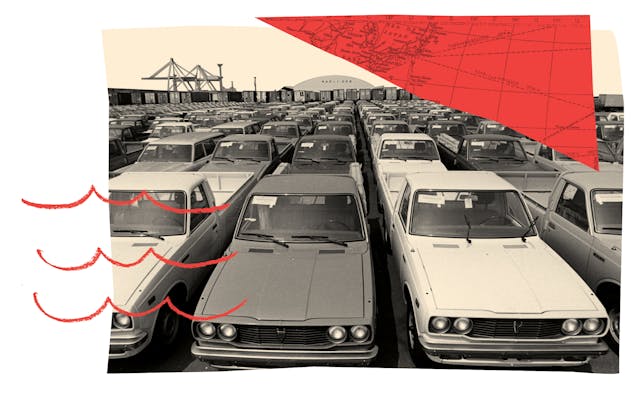

Frustration about the situation brought out lots of debate, as well as some patriotic thinking from those who thought they might be able to help boost the spirits of America and its ailing auto industry. One elaborate idea actually came close to happening, as far-fetched as it might have seemed: drive an American-built car from Japan to Detroit.

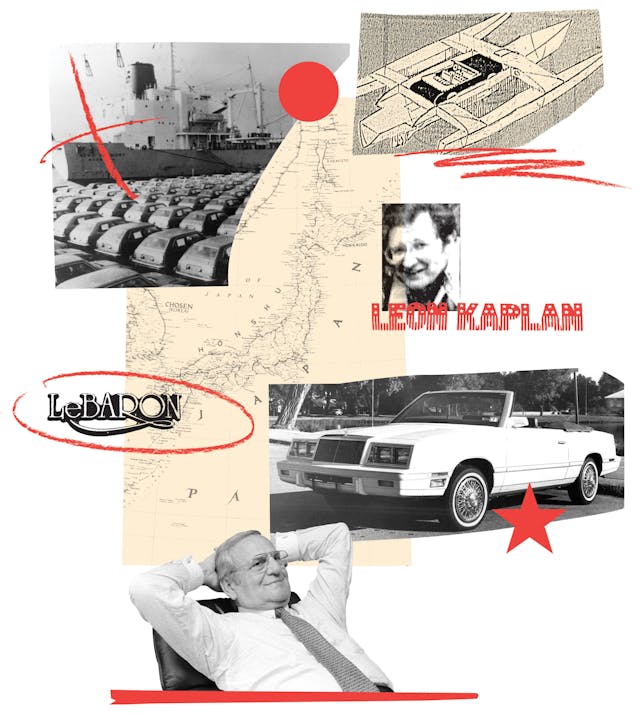

“I started to brainstorm and said, ‘What can we do? Something spectacular,’” remembers Leon Kaplan, thinking back on the events of 40-plus years ago. At the time, he was wearing many hats: repair shop owner, aviator, broadcaster, former racer. Kaplan’s Los Angeles repair shop had him working on the luxury cars of some of the movers and shakers in Hollywood and Beverly Hills going back to the 1960s. His client roster included Lucille Ball, Lloyd Bridges, Dolly Parton, Sammy Davis Jr., Debbie Reynolds, Ricardo Montalban, Shirley Jones, and a young Michael Jackson.

With his weekly Motorman radio show in Los Angeles, which he only recently retired from, as well as regular local and national television appearances, the North Carolina–born mechanic to the stars nearly hatched a scheme to have a domestic car travel under its own power more than 8000 miles from the Port of Tokyo all the way to downtown Detroit.

A red, white, and blue publicity stunt to end all publicity stunts, attempting to show that an American-built automobile was as good as anything arriving from Japan on a cargo ship.

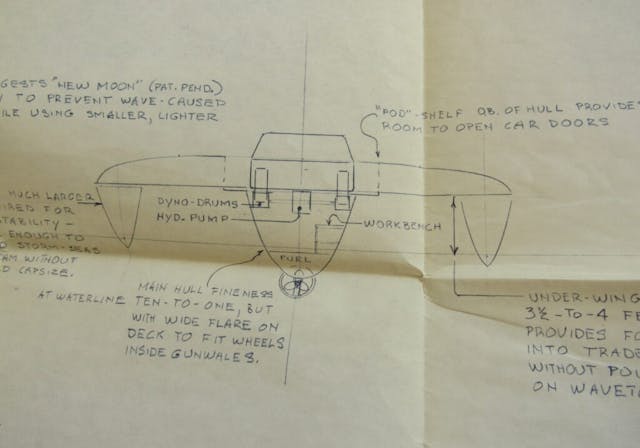

Obviously trekking across a route that was mostly over water would require some kind of gimmick, and Kaplan had come up with one. He would place a car on a custom-built vessel, with the vehicle’s drivetrain providing momentum via rollers and a hydraulic propeller system. The idea got as far as having a sailboat designer draw up plans for the 54-foot tri-hull, a layout that would help ensure stability on the high seas.

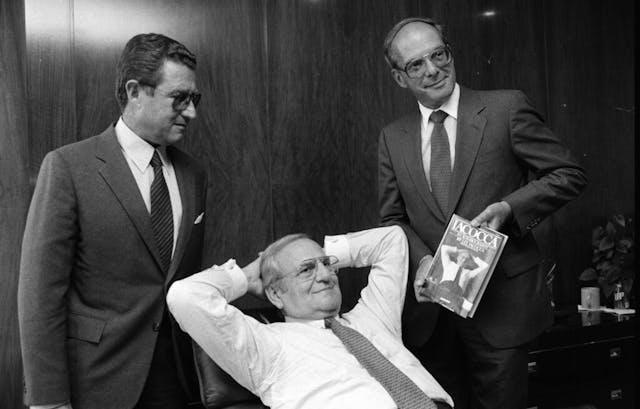

“It must have been Petersen who put me in touch with Iacocca,” said Kaplan—Petersen being publishing magnate Robert E. Petersen, a friend as well as a customer at Kaplan’s shop, of course. And yes, Lee Iacocca, the then-CEO of Chrysler who had become a household name, thanks to his side role as television pitchman for the company.

“If you can find a better car, buy it.” That was Iacocca’s stoic tag line as he was beamed into millions of American homes on a regular basis, touting the products of the newly reinvigorated Chrysler. The company seemed an ideal partner for “Leon Kaplan’s All-American Trans-Pacific Automotive Spectacular,” the initial working title for the project. Kaplan’s manager-publicist had earlier come up with a marketing packet that was shopped around to the Big Three.

Ford passed immediately; General Motors expressed mild interest, but it was Iacocca at Chrysler who really saw potential in the elaborate plan. Kaplan flew to Detroit several times to meet with the chief executive, who sought to promote his company’s upcoming flagship, the Chrysler LeBaron convertible. For that vehicle, Kaplan had to modify the design of the propulsion system a bit, as the initial layout was intended for a rear-wheel-drive car. With a LeBaron riding piggyback, the dual dynamometer-type rollers under the front wheels would be on swivels. The driven wheels would be effectively powering the ship, and when the driver turned the steering wheel, the ship’s rudder would move accordingly.

An alternative name for the floating epic was soon proposed: Chrysler Craft. At Iacocca’s insistence, “New Chrysler Corporation” was to be emblazoned on both sides of the vessel, helping highlight that the company he had come to the helm of was on a comeback. Kaplan recalls his multiple visits to Iacocca’s office, remembering that it was “nothing fancy,” located in the old Chrysler Building in Detroit. With Chrysler’s new mission of austerity and getting back on its feet, Kaplan found the visits with the CEO to be very unpretentious.

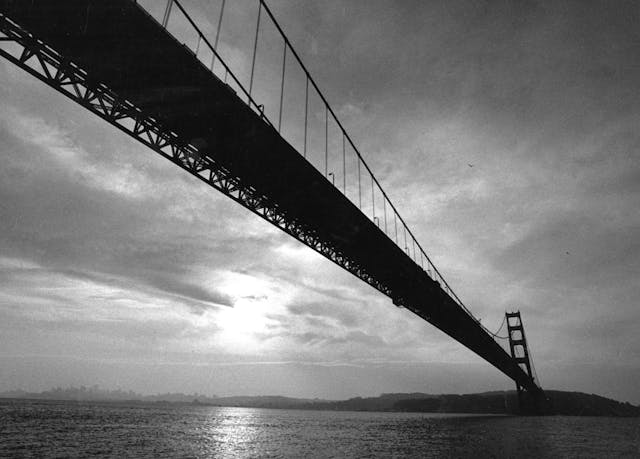

As the proposal progressed, Kaplan—who had done some off-shore boat racing—consulted with maritime experts about the best route and time of year to make the ocean voyage. Travel across the Pacific would be easiest in late spring and early summer, and a stopover in Hawaii would be a necessary part of the journey. The project was then timed to have the Chrysler Craft’s final destination be the San Francisco Bay, arriving under the Golden Gate Bridge on July 4, 1983. Along with Iacocca, the LeBaron would supposedly be welcomed back to dry land by none other than President Ronald Reagan. Widespread media coverage would pretty much be a given.

Helping with that aspect, Robert Petersen pledged his assistance in the telling of the journey’s story. Among his media company’s numerous titles at the time was a yachting magazine called Sea. That publication would cover the project extensively, and Motor Trend would undoubtedly have splashed the story on its pages as well. Kaplan’s manager had also gotten coverage commitments from Time, People, Playboy, and other outlets.

In the proposal, after landing in San Francisco the fully functional car was to be offloaded, then Kaplan would drive it to Chrysler headquarters in Detroit to finish off the trip. The tricky part would have been completed at that point, so the paved portion would have been smooth sailing, in the figurative sense.

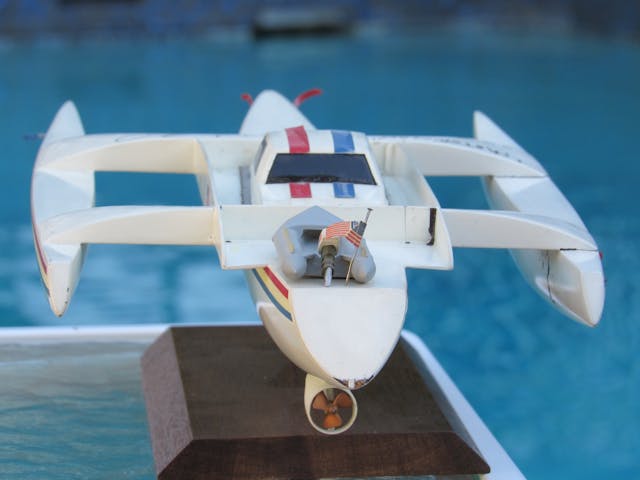

The concept had so much traction in its planning stages that Mattel signed on for rights to build toy versions of the car-ship combo. Its prototype shop built a 1:43 scale model, which Kaplan owns to this day and used during his presentations in Iacocca’s office. “I even had a special case that I used to carry it with me on airplanes,” he remembers.

Kaplan had a California-based shipbuilder lined up to construct the vessel, and he was assured they could meet the time frame laid out. There would be a launch ceremony at the Port of Long Beach, then a 50-mile shakedown run to Santa Catalina Island and back, just to make sure everything worked as designed. Once the watercraft and its attendant Chrysler were signed off as functioning properly, the whole assembly was to be loaded onto a barge for transport to Japan.

Would the car survive the obscure round-the-clock journey, great distances away from a service facility? It’s safe to assume that Chrysler’s engineering team would have prepared the most balanced, blueprinted, micrometer-measured, hand-torqued LeBaron possible. One thing was an absolute certainty: The convertible would have to run the standard 2.2-liter four-cylinder engine, and not the optional Mitsubishi-built 2.6-liter unit, for obvious reasons. Kaplan figured that the car would be most reliable with the engine running at a steady 1500 rpm, and that would yield a water speed of about 5-6 knots.

When asked about what kind of reaction this escapade might have gotten from the Japanese government, Kaplan sort of shrugged, as the proposal hadn’t really included any diplomatic aspect. Presumably, an international shipping company familiar with foreign port protocols would have been brought in for assistance. Still, once the Chrysler Craft was deployed in Japan’s territorial waters, some eyebrows surely would have been raised. Perhaps the philosophy of “It’s easier to beg forgiveness than ask permission” was the game plan.

In the planning, other logistical needs were taken into consideration. For example, while the trimaran was designed to have a working repair pit under the car, along with storage for spare parts, tools, and other necessities (including bunks for sleeping below deck), a support vessel would be needed to tag along on the two-week crossing. For that, a ship from the Pacific tuna fleet out of San Diego was to be hired. The crews of those large fishing boats were used to being at sea for weeks at a time, had maritime knowledge of the waters, and the ship could obviously carry whatever supplies might be needed.

For example, hundreds of gallons of unleaded gasoline to refuel the car along the way. To ferry fuel, supplies, and relief drivers to the Chrysler Craft, Kaplan revised the design to have a slanted ramp at the stern. That way, an inflatable Zodiac boat could land, offload containers of fuel and other things, then easily slide off and make its way back to the nearby support ship. The tuna boat would also provide quarters for sleeping, showers, meals, and so forth.

Kaplan was to be the lead driver, most importantly at the helm of the top-down LeBaron as it made its triumphant arrival under the Golden Gate. He had enlisted some boating and sailing friends as relief drivers, though he told very few people about the project beyond those directly involved.

Everything seemed to be in place, except for a key element: a signed contract—and the ensuing funds—from Chrysler. The cost to pull off everything was calculated to be approximately $1.1 million, chump change for a major auto manufacturer, even in 1982. But perhaps not a manufacturer under the continuing scrutiny of Congress. The U.S. Government had guaranteed $1.5 billion in bank loans a couple of years earlier in order for the company to stave off bankruptcy. Part of the agreement to get the loans was that Chrysler cut the costs that had previously soured its balance sheets. Splashy publicity hijinks were probably not considered a necessary seven-figure expenditure in the eyes of the company’s chief financial officer.

As the clock ticked toward the mid-1983 target for the voyage, Kaplan couldn’t get a final commitment from Iacocca. He did have secondary sponsorship agreements from Hawaiian Punch and Goodyear, but title sponsor Chrysler needed to come through with the bulk of the money.

Time went on, and Kaplan did occasionally hear from Iacocca, who said he was still interested in the idea, “Maybe next year,” as Kaplan recalls. But as Chrysler steamed ahead through the ’80s with a renewed spirit of innovation, early payback of the loans, and new-found profitability, the planned Chrysler Craft got stuck in eternal dry dock.

Today, Kaplan looks back fondly on the project, reflecting on the countless hours he invested trying to bring it to fruition. If it had happened successfully, it truly could have been spectacular and gone into the history books. Who knows, Chrysler might have even created a TV spot about it. Imagine Lee Iacocca standing proudly akimbo atop the ship, with the LeBaron just behind him, and the Golden Gate Bridge off in the distance. “If you can find a better car, drive it across the Pacific Ocean!”

The Chrysler Craft: An Unrealized Dream

To embark on such a voyage, the vessel toting the LeBaron would have to be large and stable enough to handle the deep blue Pacific, but also small and light enough to be propelled by a passenger car with a rather meek engine. Kaplan enlisted Searunner Multihulls of Virginia, run by two experienced ocean sailors and designers, John Marples and Jim Brown. It was Brown who drew up the initial 54-foot trimaran plans, with the center hull shaped to carry the Chrysler. Marples still remembers the project and recently said, “I was sorry that the design was never built.” So is Kaplan.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

This would have been cool to see even with the K-car in the middle.

I think the problem with the bean counters is that they simply couldn’t see this as part of their overall marketing budget. If Chrysler was going to spend $X on marketing that year, why couldn’t $1.1M be allocated to this? The tangential advertising would have given it far greater a return on investment. More than likely was the fear that any major breakdown (a significant risk for a Chrysler in the ’80s) would have turned that expensive marketing campaign into a major embarrassment for the company. The car would have needed a couple of oil changes and probably at least one minor service along the way, even if nothing actually broke down.

It wasn’t just Chrysler’s bean counters. As the story said, Chrysler was under the microscope of government bean counters and a Congress that had just loaned Chrysler money. Unlike these days when government throws billons at half baked pie-in-the-sky “green” schemes that often go bankrupt after they’ve lined the pockets of the right people, back then Congress kept a tighter control on spending. Not saying they didn’t blow our tax dollars, but they did keep a tighter reign on it.

Leon had actually planned to service the car along the way, just as you suggest. The design of the boat called for a “repair pit” underneath the car for just such a thing, as well as places to carry tools and spare parts. And Goodyear had signed on as a sponsor, so their provided tires were to have been rotated during the journey as well.

Thanks to Hagerty for bringing us interesting stories like this one.

The last time the auto makers came to Washington with their hands out, there was a major stink about how they all flew in on their private jets. Being a GM fan if I was in the marketing department, I would have had all those executives each drive a new model from across their platform on a cross country promotional tour that ended in Washington. That would have served 2 purposes > Free advertisement and not looking out of touch.

The later LeBaron convertibles were probably better looking. Does anyone remember the LeBaron GTS, around 1986 I believe. Turbo charged and touted to be a BMW beater. I had a black one with red interior. Yes that combination has spanned the years. It wasn’t a bad car and could easily breach the 100 MPH mark without too much effort. Go try to find one now. Would that be a collector car?

After having been around the hobby for a minute or two, you think you’ve heard of and seen everything…..then something like this comes along, slaps you upside the head, and makes you realize that you ain’t seen nothin’ yet! 😉

Cool story!

I wonder who got the idea from who when that family of Cubans who made a floating 53 Buick many years ago to escape to Florida made basically the same thing and it worked. That should have been sent to a museum but some government fool sank it.