Blind at 58, one man chose to keep loving life—and his classic Plymouth

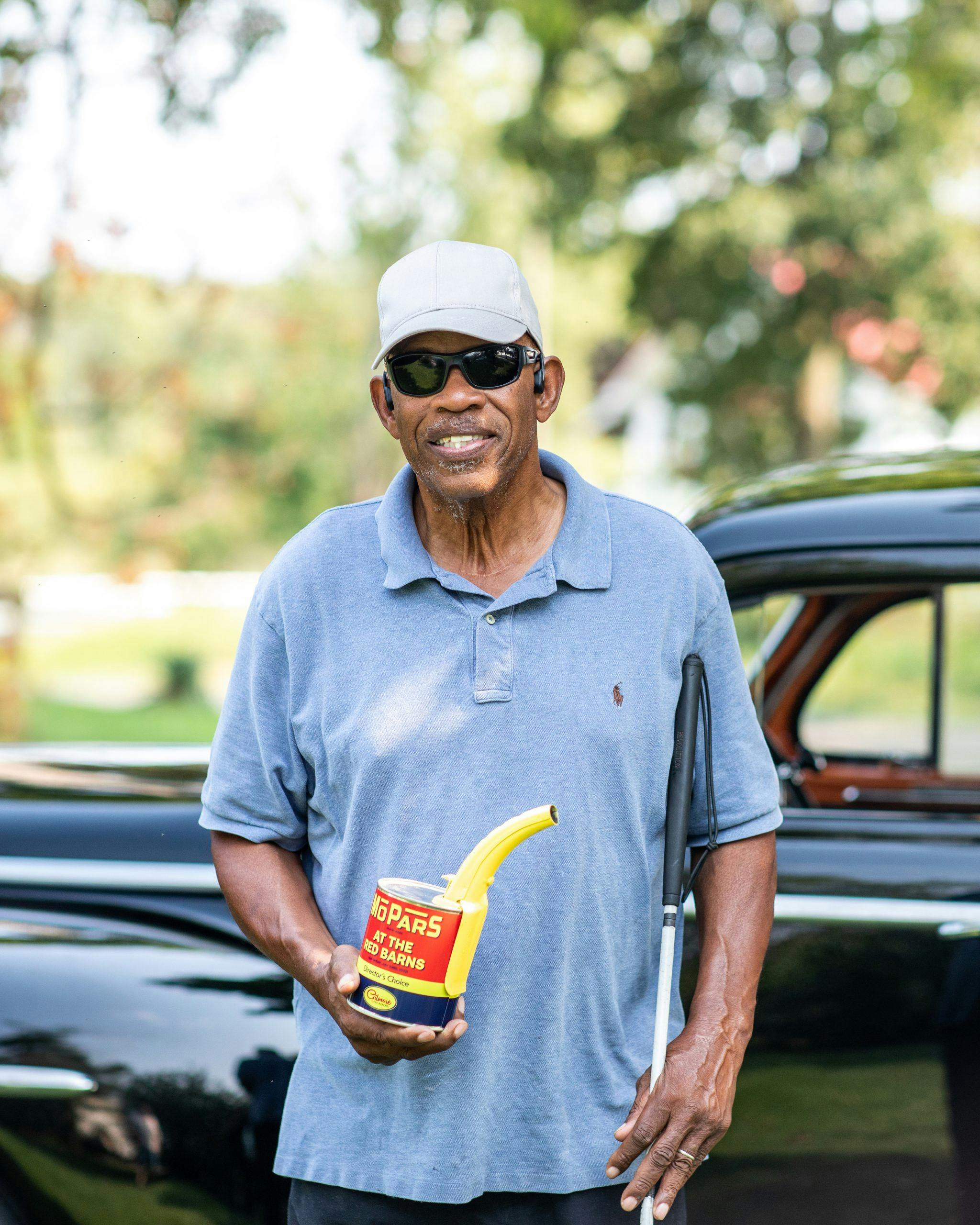

Bill Chapman may have lost his eyesight, but he hasn’t lost his way. The 72-year-old Michigan man, who suffered optic nerve damage and went blind more than a decade ago, relies on his other senses to enjoy cooking, woodworking, kayaking, and playing cards, and he treasures his 1947 Plymouth Special Deluxe four-door sedan, even though he can’t drive it.

Upbeat and enthusiastic, Chapman says he doesn’t need to see his 1947 Plymouth Special Deluxe four-door sedan to appreciate it.

“I know what my car looks like, and I know what it’s supposed to feel like,” he says in the velvety, deep tones of a radio DJ, running his fingers over the black Plymouth’s front fender. “My car has a certain feel, a certain smell, a certain sound. I know that engine. I’ll start it up and back it down the driveway—with someone helping me, of course. That’s the highlight of my day.”

Anyone who spends time with Chapman feel the same about him. He has a delightful sense of humor and an infectious laugh, and he exercises both often. Chapman says he’s always been that way.

“I’m a people person,” he says. “I worked for the Kalamazoo [County] Circuit Court for 32 years as a probation officer and juvenile home director. I worked with kids and helped ex-offenders land jobs. I loved what I did. I retired in 2005, but I still did a lot of things. I played golf, I played softball, I kayaked … I was very active.”

He still is, even though his life is different than he imagined it.

Chapman grew up in South Bend, Indiana, where he was a strong student and athlete. He began working in the Michigan court system in 1973 after graduating from Kalamazoo College with a degree in sociology. After a fulfilling career that spanned three decades, he was eager to begin the next chapter of his life when he retired at age 55. That included spending more time with his wife, Pam, and their three sons and daughter. (One of the Chapmans’ sons passed away several years ago.)

Retirement also promised fun with friends and the opportunity for Bill to enjoy his beloved ’47 Plymouth, which was a gift from his wife.

“Growing up, I had a picture of my father and his father in front of a whaleback [style] car,” Chapman says. “It looked so great that I said, ‘I’m going to get one of those someday.’ Then 25 years ago my wife surprised me with this.

“It needed some work, and my buddies helped me out with it. Every year there was something else to work on.”

To learn more about the car, Chapman joined the Michigan region of the Plymouth Owners Club. “These guys had so much knowledge,” he says. “I’d ask about something and they’d say, ‘Just go here’ or ‘Just go there.’ I got into some car shows, and just the camaraderie is something, you know? You can feel the enthusiasm. It’s fun.”

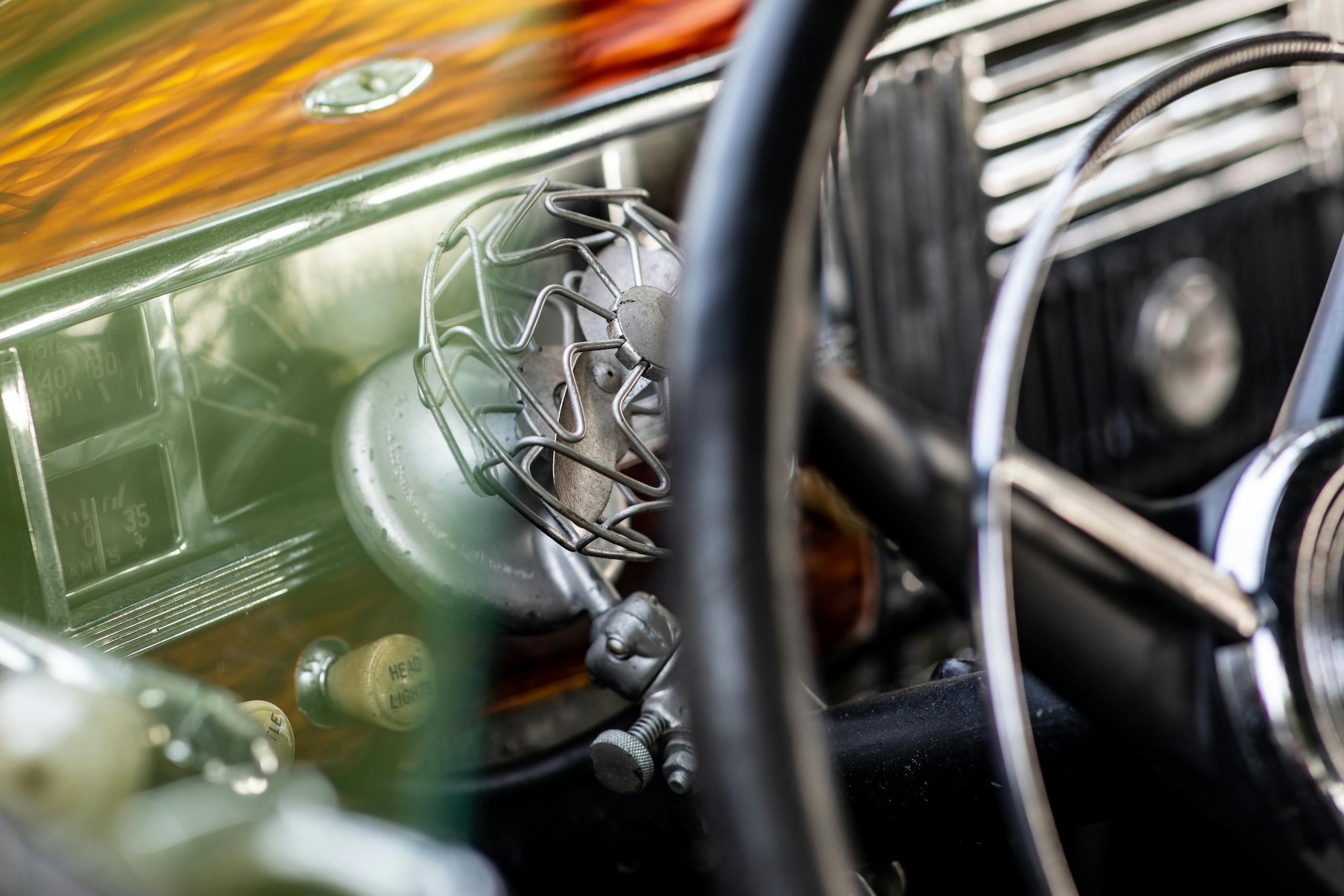

Chapman describes some of the attributes of his Special Deluxe, quickly followed by his worst memory of it.

“It has a flathead six [218 cubic inches, 95 horsepower], suicide doors, and it’s pretty much all original except for the paint job,” he says. “Ohhh, the paint job. Let me tell ya about the paint job … It had a C-minus paint job when I got it, and I met a guy who promised he could give it an A+ paint job for $1000. Well, you get what you pay for, and I got an F paint job. I was sick, man. I couldn’t leave it like that. It had to be taken down to the metal and repainted right. Dan saved it.”

Dan is Dan Penn, who has known Chapman since 1974 and once taught a group of at-risk youth how to do bodywork—through a grant that Chapman arranged. (“Two of them are still doing that work,” Penn says, “so that makes me proud.”) Penn lives about an hour from Chapman, and he spent a year working on the Plymouth. Chapman says it was well worth the wait. “I was amazed. Oh, man. I could still see a little then, and it was beautiful.”

Chapman says he took the Plymouth to some car shows and quickly won four or five awards. “People seem to like it,” he says of his pride and joy. “I think it looks like something a gangster would drive. I put a violin case in the back seat, like in the Al Capone days [when a violin case might contain a machine gun]. People think that’s cool.”

At about the same time that Plymouth received its new paint job, Chapman began having trouble with his eyesight. He couldn’t see as clearly, which happens to most of us as we age, but it was more than that—the world seemed to be growing darker.

“I went to the best of the best doctors (at University of Michigan Hospital) in Ann Arbor, and I was diagnosed with optic nerve neuropathy,” Bill recalls. “Stop lights were hard to see. I saw shadows. I went into denial, but it kept getting worse. During one visit, my doctor said, ‘You’re blind, Bill—legally blind.’ I didn’t want to believe it. I said, ‘What are you talking about?’ I was in denial for six to eight months. I was faking it. I was bumping into people and saying, ‘Oh, excuse me’ … I was just trying to get by.”

Chapman’s wife decided it was time for a heart-to-heart talk. “Pam helped me. Fifty years of wedded bliss, I tell ya,” Bill says with a smile. “She said, ‘Bill, you can’t see. You need to get involved with the blind center and learn how to function.’ I let my ego get in the way, but finally, when I had tunnel vision, I knew.

“It tripped me out at first, but I decided to live. People in my situation have a high rate of suicide, and I can relate—I can see how that would happen. But for me, life don’t stop because you lose your sight. I was going to do everything I could to keep living.”

For 13 weeks—Monday through Friday, 8 a.m. to 4 p.m.—Chapman attended classes, determined to thrive. “I learned cane mobility, Braille, cooking, and woodworking—yes, woodworking. I found out I really enjoy it,” he says. He also became good at it, and he now uses his talent to support Blind Truths, a Kalamazoo organization that helps people who are blind or have low vision. Chapman, who vowed to stay in touch with everyone he had attended classes with, is the organization’s president.

“I make clocks and plaques, and I use the money I get to help out other people in our group who are struggling, so when they get on their feet they can help out other people,” he says. “You never know what a person is going through. We have to encourage each other and show each other what’s possible.”

Turns out, there’s plenty. While Bill’s cane serves as his “eyes,” modern technology provides services that previous generations could only dream of. For that reason, his cellphone is his constant companion. In the end, Chapman says, simple determination is the key. He believes that for every hurdle there’s a solution, and quitting is not an option.

His friend, Dan Penn, can vouch for that. “As long as I’ve known Bill, he’s never let anything slow him down.”

We visited Penn in Sturgis, near the Indiana border, to see Chapman’s Plymouth. Dan is preparing to fix a dent that Bill discovered in the rear of the car, near the license plate. Chapman didn’t see the ding, of course, but he felt it after attending the Gilmore Car Museum’s “Mopars at the Red Barn” show in Hickory Corners, Michigan, in July. “Somebody must have backed into me,” he says. “So I knew who to call to help me.”

Penn is happy to do it, and he isn’t the only friend of Bill’s who is eager to lend a hand when asked. Chapman says he has “a couple of guys” who drive him to car shows, and once he’s there, his Plymouth always draws raves.

“I appreciate it when people give the car compliments, because I get to see it through their eyes,” Chapman says. “It’s fulfilling. It makes me smile.”

With that said, he decides to let us in on a little secret.

“I can’t drive my car on the road anymore, of course, but sometimes we go into an empty high school parking lot so I can drive it 10 feet or so,” he says with a laugh. “I have them videotape me, and I wave goodbye so it looks like I’m driving away. I enjoy showing that to people—they can’t believe it. They say, ‘You can’t drive anymore,’ and I say, ‘Wanna see?’”

Chapman has such a can-do attitude that, for a split second, you believe he could do the impossible.

“Being blind isn’t the end of the world,” Chapman says. “The only limitations that blind people have are the limitations they put on themselves. And God isn’t finished with me yet.”

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it.

For some reason, reading this made my eyes wet. Wonder if it’s allergy season.

Thank you for your comment, it means a lot to me.

Bill Chapman,

I love the story! Your sense of humor driving away! I also love the last sentence. God isn’t finished with me yet. This gives me hope to see you someday in heaven and have a visit when you’re healed and seeing again. Keep the faith brother! God bless you!

Maybe you were cutting onions. This often happens when I am reading a touching story for some reason.

beautiful car, beautiful story.

Thank You

Bill, you have a very nice car sir. I’m about a decade younger than you, your story and attitude in life is an inspiration to all.

Thank you for sharing it with all of us. ~Pat

Great Owner !! It’s nice to remember past images.

The Plymouth looks New! Brings back a lot of memories of my 46 Plymouth when I was 15-I had fender skirts, shaved trunk, blue moon wheel covers with lights in fenders, also I mounted radio on rear shelf so I could mount antenna on rear fender—In my mind I was Very Cool!!

Great story

Congrats Bill you make the impossible]seem ordinary always

Truly an amazing inspirational story. And, an incredible car as well. It is somewhat similar to my father’s favorite car which was a 1950 Dodge Coronet. Keep up the great work and great attitude.

Wonderful story–this should invigorate even the most calloused of individuals! GO, Bill!!!

Keep on Keeping ON.

Terrific car and story. I hope I handle future health challenges as gracefully and cheerfully as Bill has. I’m sure it was not easy to come to grips with initially. Shows the power of positive attitude, friendship and love.

Profound thanks, Jeff Peek and Hagerty, for this story about a strong and noble man, Bill Chapman, his wife, his friend fine Dan Penn, his well done car. A story that could befall any of us. Thank you.

I read Hagerty from a work computer and for whatever reason, it doesn’t display the photographs. If the story interests me enough, I’ll cut/paste the title into a search engine and view the images, which load blurry then clear up in 2-3 seconds. (Again, don’t ask me why, but this works.) I mention all this because it’s interesting how your mind creates images in the absence of any input from your eyes. Obviously this story did interest me enough to view the images.

Funny enough, only my generic image of a 40’s Plymouth was accurate. For some reason I expected some kind of patched-up hotrod, not a gleaming restoration. Bill’s friend does know his stuff. Beautiful car.

For the record, my mind’s eye also got Bill wrong. upon seeing the blurry, grassy setting, the cane (looking like a golf club) and the sunglasses… My first thought was “What does Tiger Woods have to do with this?” I thought Bill might get a laugh from that.

As a matter of coincidence, friends and I were discussing the idea of going blind just a few days ago. Some said they’d never be able to come back from it, but I took a side that sounds like what Bill did in real life. I’m glad to read that, for my life has been blessed with too much good to give up on. It’s inspirational to read that from someone who’s lived it.

My hero.

Behind every inspiring story is a great woman and a good friend!

1

Excellent story and a really cool car.

Any chance we could buy some of Bill’s woodwork?

Yes! You can find it on the Blind Truths website (click the link in the story). Thank you, he’ll be thrilled that you’re interested!

I admire this man for not for what he has over come but for the good nature he has. God has blessed a many of persons through him I’m sure. Very nice car also. Thanks for being you.